More than seven months into the coronavirus pandemic, and just days from the crucial US elections, the world has learned a great deal about how the COVID-19 outbreak is shaping global politics. Indeed, it is likely that there has never been so much world-wide polling about any one issue in such a short period of time. During this period GQR has collected and analyzed nearly 2,000 polls from over 100 countries. There have also been over a dozen major elections since the start of pandemic that provide further clues into how this global health crisis is shaping global political outcomes.

In this edition, we summarize the key lessons that have emerged from our review of global polling since the start of the pandemic. We also analyze the pandemic’s impact on the important recent elections in New Zealand and Bolivia.

This is the twentieth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. The 10 most important insights from global polling over these months, which we analyze in more detail below, include:

- The coronavirus crisis initially boosted approval ratings for most leaders world-wide, but as governments developed varied responses to the pandemic, patterns of public support began to vary as well. At this point, the pandemic has tended to depress public approval for leaders with populistic responses, and has tended to boost public approval for those who responded with science-based policies and sustained competence.

- COVID-19 appears to have only a small negative impact on voter turnout overall globally, with turnout actually increasing on some countries that have taken steps to make voting safer.

- Countries that moved toward quick economic re-opening often undermined public confidence in health conditions, which may have further undermined economic conditions. In most countries, publics prioritized protecting health over protecting economic growth.

- Even before the new spikes in cases that have occurred in much of the world in recent weeks, publics showed high concern over a resurgence of the virus, and doubted they would feel comfortable resuming normal economic, social, and educational activities.

- World-wide, the elderly have been more alarmed about the pandemic, and more likely to prioritize health protection over economic re-opening.

- The pandemic has had differential impacts world-wide, with harder impacts along lines of class, race, and ethnicity. Even though there is evidence the disease strikes harder at men, women have tended to express more concern about the pandemic in most countries, although in some cases this reflects gender differences in party alignment.

- During the course of the pandemic, many countries have seen big shifts in public attitudes toward wearing protecting masks; the US, however, is one of the only countries in which such attitudes polarized along partisan lines.

- News consumption has climbed during the pandemic; while publics in some countries tend to feel the media has exaggerated the threat, the dominant pattern is one of more trust in the media than in the past.

- The pandemic has heightened the profile and authority of scientists and health officials in most countries.

- The pandemic has spawned a crisis for democracy world-wide, providing leaders and governments with opportunities to suppress opponents, limit political speech, steal resources, and restrict media.

Major Insights

The past seven months have revealed multiple ways that the coronavirus pandemic is shaping national politics worldwide. Our analysis of nearly 2,000 polls regarding the pandemic world-wide, along with the results of over a dozen major elections during this period, underscore major 10 insights:

1. The coronavirus crisis initially boosted approval ratings for most leaders world-wide, but as governments developed varying responses to the pandemic, patterns of public support began to vary as well. At this point, the pandemic has tended to depress public approval for leaders who provided populistic responses, and has tended to boost approval for those who responded with science-based policies and sustained competence.

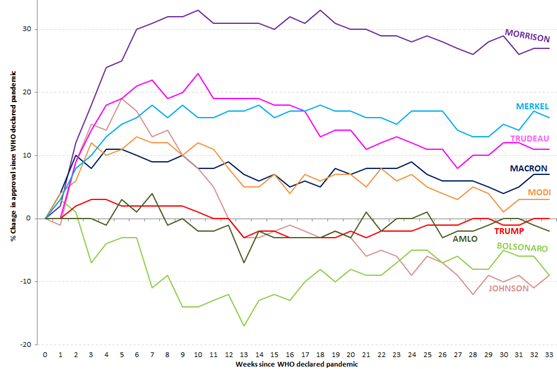

As we noted in the second edition of this series, by late March, within just weeks of the start of the pandemic, there were signs of the health crisis helping to boost approval ratings of leaders world-wide. But as leaders diverged in their policy responses, so did their approval ratings. As Figure 1 shows, the only four major world leaders who do not now have higher approval ratings than when the WHO declared the pandemic on March 11 are also those who have arguably been among those with the most populistic responses to the crisis – President Trump, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, and Mexican President Andres Lopez Manuel Obrador.

Figure 1: Approval ratings of world leaders, relative to March 11 start of pandemic (Morning Consult data; layout concept from The Economist)

Public approval has followed results more than rhetoric, and positive results on COVID have tended to follow science. Leaders who have consistently pursued a science-based approach, like New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern or German Chancellor Angela Merkel, have seen sustained improvement in their public support. (See the note below on the recent New Zealand elections.) Publics are proving to be unforgiving, even for leaders who initially produced positive results in battling the pandemic. In places such as Montenegro (as we discussed in Issue #17), late spikes in COVID-19 have quickly undermined the strong approval ratings that some leaders earned during the early days of the pandemic.

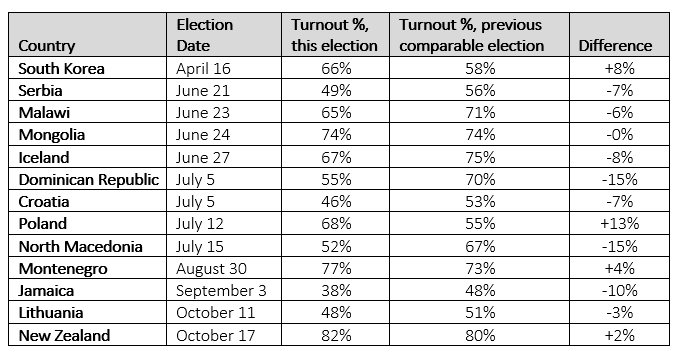

2. COVID-19 appears to have only a small negative impact on voter turnout overall globally, with turnout actually increasing in some countries that have taken steps to make voting safer

In the major national elections since the start of the pandemic, COVID-19 may have somewhat depressed turnout overall, but not uniformly, and not by very much. As Figure 2 shows, across 13 elections during this period, 8 saw lower turnout than in the relevant previous election, 1 saw no change, and 4 saw higher turnout – including places like South Korea and New Zealand, which initiated major efforts to make voting safe and convenient during the pandemic. (We have excluded from this analysis Bolivia and Singapore, which have compulsory voting; and countries such as Guinea and Tanzania with elections that were not free and fair.) Indeed, some of the cases of lower turnout can be explained by other extenuating circumstances – such as in Serbia, where the opposition boycotted the election, or in Iceland, where the President faced no real opposition. Even facing a pandemic, voters seem determined to make their voices heard.

Figure 2: Turnout in countries with major national elections since the start of the pandemic.

3. Countries that moved toward quick economic re-opening often undermined public confidence in health conditions, which may have further undermined economic conditions. In most countries, publics prioritized protecting health over protecting economic growth.

As discussed in Issue #11, publics in most countries with relevant polling data (including the US, UK, Australia, Canada, and Israel) were more worried about re-opening their economies too quickly rather than too slowly. Those such as Israel that failed to heed this sense of caution have often paid a price, not only in terms of a spike in cases, but also in falling public confidence about the government’s handling of the pandemic. Analyses of the US and Canada – neighbors with contiguous and similar economies – are revealing on this point: with more effective policies on containing the pandemic, Canadians are broadly more confident about such economic activities as going to a shopping mall or proceeding with home repairs.

4. Even before the new spikes in cases that have occurred in much of the world in recent weeks, publics showed high concern over a resurgence of the virus, and doubted they would feel comfortable resuming normal economic, social, and educational activities.

Even before cases began to spike again in recent weeks in Europe, the US, and elsewhere, majorities in most countries with available survey data felt uncomfortable returning to work; pluralities felt uncomfortable sending children back to school. Even from the early weeks of the pandemic, there was concern about a second wave of the kind that is now appearing in much of the Northern Hemisphere.

5. World-wide, the elderly have been more alarmed about the pandemic, and more likely to prioritize health protection over economic re-opening.

As noted in Issue #9, the elderly in most countries have stronger levels of concern about the coronavirus than the population in general. This is hardly surprising given their susceptibility to the disease. It helps explain why older citizens, even more than their younger counterparts, have tended to be more focused on protecting health rather than speeding economic re-opening, in most countries where polling on such questions is available.

6. The pandemic has had differential impacts world-wide, with harder impacts along lines of class, race, and ethnicity. Even though there is evidence the disease strikes harder at men, women have tended to express more concern about the pandemic in most countries, although in some cases this reflects gender differences in party alignment.

Epidemiological data has shown the pandemic taking a disproportionate toll on lower-income individuals and members of racial and ethnic minorities. The global survey data underscores this finding, revealing that lower income respondents in many countries expect or report more negative impact from the disease on their jobs or incomes. Moreover, lower income respondents world-wide report less ability to make economic adjustments to the pandemic, such as less ability to work from home. Although COVID-19 appears to afflict men somewhat more than women, women in most countries express more concern about the disease and its impacts.

7. During the course of the pandemic, many countries have seen big shifts in public attitudes toward wearing protecting masks; the US, however, is one of the only countries in which such attitudes polarized along partisan lines.

From the earliest days of the pandemic, most Asian countries reported majorities of their populations wearing facemasks; countries in most other regions only shifted toward majority mask-wearing later, often around May or June. The US emerged as one of the few countries where attitudes toward wearing face masks showed major differences based on partisanship.

8. News consumption climbed during the pandemic; while publics in some countries tend to feel the media has exaggerated the threat, the dominant pattern is one of more trust in the media than in the past.

Surveys show a global surge in news-watching since March, with publics in most countries relying on television more than social media for news about the pandemic. While majorities in some countries (notably India, Russia, and Mexico) felt the media were exaggerating the danger from COVID-19, that is a minority sentiment in far more countries, especially those that have seen higher numbers of cases of COVID-19. Indeed, as noted in Issue #6, a YouGov/Reuters Institute study found that in all 6 countries surveyed (US, UK, German, Spain, Brazil, South Korea) trust in the media had moved from minority levels in 2019 to majority levels in 2020.

9. The pandemic has heightened the profile and authority of scientists and health officials in most countries.

As summarized in Issue #19, in most countries with relevant survey data, publics see scientists and health professionals as the figures they trust most to provide accurate information on the pandemic. Epidemiological experts such as Dr. Anthony Fauci in the US have become household names in many countries as publics look for guidance on how to protect their health. It may be, as a result, that the pandemic is helping to raise overall global confidence in science, which already had been on the rise in recent decades, according to long-running tracking such as in the World Values Survey.

10. The pandemic has spawned a crisis for democracy world-wide, providing leaders and governments with opportunities to suppress opponents, limit political speech, steal resources, and restrict media.

GQR’s global survey of democracy activists, conducted for Freedom House and published earlier this month, found the pandemic is triggering not only a health crisis and an economic crisis, but also a democracy crisis, with 75% of the respondents saying the pandemic has undermined democracy and human rights in their country of focus. Even since publication of the report, deeply fraudulent elections in places such as Tanzania and Guinea have underscored the ability of authoritarian leaders to suppress their people’s rights at a time when the world is distracted by the pandemic.

Election results in New Zealand and Bolivia continue to show how government responses to COVID-19 are shaping global election results.

The landslide re-election of New Zealand’s Labour government, led by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, is one of the clearest electoral referendums yet on a government’s positive handling of the pandemic. Labour won 64 seats of the 120-seat parliament, its first outright majority since “mixed member proportional representation” was introduced in 1996. As noted above, turnout actually increased slightly from 2017, up from about 80% to 82%, with a record number of nearly 2 million people casting their ballots early, thanks in part to a campaign encouraging early voting, in order to reduce lines at voting places to protect against COVID-19.

With a population of 4.9 million, and despite its proximity to China, New Zealand has recorded just 1,923 coronavirus cases and 25 deaths since WHO declared a public health emergency on January 30. The success is attributed to a swift, early nation-wide lockdown on March 26 supplemented by strong testing, contract tracing, and treatment systems for those infected.

Ardern became the face of the country’s widely-praised COVID-19 response, continually updating the country through daily briefings and frequent nighttime Facebook Live sessions, in which she answered questions, emphasized nationwide solidarity, and reassured children – telling them, for example, that the tooth fairy was an essential worker.

Other factors also buoyed Ardern’s popularity, including her response to the 2019 Christchurch terrorist attack. Leadership changes within the opposition also help explain the outcome. Yet as recently as January, polls showed a contested election between Labour and the opposition National Party. The pandemic was central to Labour’s ultimately victory, with Ardern actively citing her government’s response to COVID-19 as part of her case for re-election. Indeed, she kicked-off her campaign August by saying, “When people ask, is this a COVID election, my answer is yes, it is.”

In Bolivia’s October 18 elections, Luis Arce of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) won in the first round of the presidential elections by gaining a 55% majority. MAS founder Evo Morales served as president for 13 years after 2006, but was forced to flee the country last November after charges by the OAS and others that he had defrauded the October 2019 election. MAS was able to rebound from those events, in part, due to its criticism of the poor handling of the coronavirus pandemic by President Jeanine Añez, who formed an interim government after Morale’s flight from Bolivia. In May, Añez’s health minister was arrested for corruption after reports that his ministry had massively overpaid on procurement of respirators, implying corruption.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 19 installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through October 15, reviewed a total of 1,899 polls from 110 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 74 polls, covering 46 geographies. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Guinea-Conakry

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The 19 earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.