an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

This is the ninth in a series of weekly papers from GQR summarizing and analyzing all available data on global opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here.

This edition of Pandemic PollWatch[2] examines global opinion data regarding the elderly – the group most at risk from the coronavirus, and a key voting bloc in most country’s elections. Major insights regarding attitudes of the elderly worldwide include:

- The elderly tend to be more concerned about COVID-19 than other age groups. This is hardly surprising, given their vulnerability to the disease; indeed, it is surprising that their levels of concern are not higher.

- Given their higher health risks, elderly voters worldwide are also more likely than average to prioritize health protection above economic re-opening, although there are exceptions to this pattern.

- In most of the countries with such data, elderly voters give their national governments somewhat higher-than-average job approval ratings for handling COVID-19. Again, there are exceptions to this pattern, and in some countries (e.g., the UK) the higher job approval from older voters partly reflects the tilt among older voters toward the party in power.

- In the US, there are signs of a potential transition in the views of elderly Americans. Those age 65 and older gave Donald Trump an 8-point margin in the 2016 vote, but some polls show a significant decline in their support for Trump’s handling of COVID-19, with some signs of deterioration in Trump’s support on general election ballot tests against Democrat Joe Biden.

Major Insights

Across most countries with polling data, the elderly are more worried about contracting COVID-19

The elderly are at the center of the coronavirus pandemic. They are far more likely to be hurt by the disease. A study published in the Lancet estimates the death rate is 20 times higher among those age 60 and over, compared to those under 60. According to the CDC, 80% of US deaths from COVID-19 have been among those aged 65 or older.

The elderly also are particularly influential in most societies. The 2014 World Values Survey finds 71% of publics across 59 countries (results not weighted for country population) view people over 70 with respect, and most of these (41%) say they are “very likely” to view the elderly with respect. In most countries where voting is not mandatory, older citizens also tend to vote in higher numbers.

As the primary victims of the coronavirus, and as a particularly respected and influential voting bloc in most countries, the opinions of the elderly therefore deserve special attention. Their opinions are also critical because there are important questions of inter-generational equity imbedded in tradeoffs between health restrictions and economic activity, and in financing pandemic-related spending measures, which in many cases are being financed by debt and will be paid off long into the future.

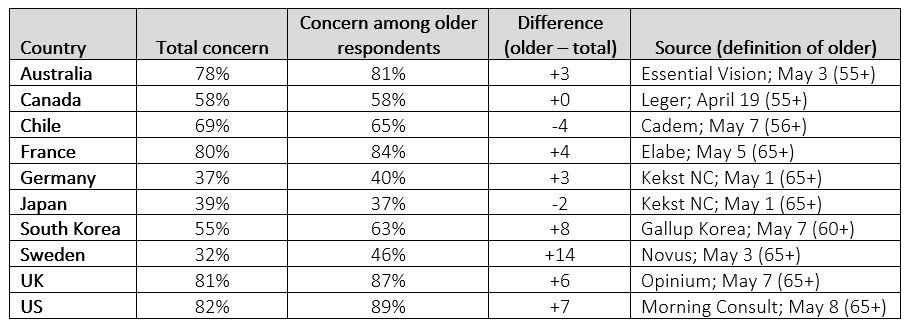

As a starting point, global opinion data show that the elderly are generally more likely to be concerned about the coronavirus. As Table 1 shows, personal concern about the virus is higher in 7 of 10 countries for which age-differentiated data is publicly available. The fact that the elderly are more concerned is not surprising, given their greater vulnerability to COVID-19; if anything, it is somewhat surprising that they are not even more alarmed, relative to their younger counterparts.

Table 1: personal concern about the coronavirus, older respondents compared to total[3] The elderly also tend to put more emphasis on health protection relative to economic re-opening, compared to national polling averages, and are more willing to comply with health-related restrictions.

The elderly also tend to put more emphasis on health protection relative to economic re-opening, compared to national polling averages, and are more willing to comply with health-related restrictions.

Given their higher concern about the virus (and, perhaps, because more of them are not in the workforce), older respondents also tend to put a higher priority on dealing with the health implications of the pandemic than the economic challenges.

In the UK, for example, a May 6 Redfield and Wilton survey found a 62-38% majority of all respondents more concerned with faster rather than slower relaxation of current lockdown measures.[4] But among those aged 65 and older, the majority was significantly larger, 70-30%. Similarly, a Kekst NC May 1 survey in the US found that respondents 65 years and older were more likely to say the government’s priority should be on health, even if that means additional economic costs; they favored this idea by 67%, compared to 57% among all respondents.[5] In Japan, with the same question, Kekst found 73% of seniors favoring health over economic imperatives, compared to 60% among the total population. The pattern is not universal, however: in Kekst’s survey in Germany, the share of the elderly choosing this option was no higher than average (48% among the elderly; 49% overall).

Older people also appear more likely to be willing to comply with pandemic-related restrictions on their activities. (That willingness may reflect many factors beyond health risk, including relative lack of work and child-raising responsibilities, greater general obedience to authority, etc.) In Ukraine, an April 30 KIIS survey finds 73% of those ages 60 and older are willing to adhere to quarantine measures “as much as necessary,” compared to only 59% among adults overall. Similarly, an April 29 Turu-uuringute AS poll in Estonia found that 80% of Estonians 65 and older say they are following all government instructions regarding the pandemic, compared to 70% for all adults.

In most places, older voters give their governments somewhat higher-than-average job approval ratings for handling the COVID-19 pandemic, although there are exceptions.

Despite the heightened worries of the elderly, in many countries they are more likely to give their governments positive marks on their handling of the pandemic. Examples include:

- Bolivia: an April 26 Captura Consulting poll finds 84% approval for President Jeanine Añez and her government on COVID-19 among those ages 45-65 (the highest age range provided), compared to 66% overall.

- Canada: an April 19 Leger poll found 81% of Canadians satisfied with the measures the federal government has put in place against the coronavirus, compared to 77% overall.

- Chile: the May 7 Cadem poll found 50% of those 56 years and older give President Sebastián Piñera positive marks for his handling of COVID-19, compared to 32% from the total public.

- Greece: a May 5 About People survey found 74% of those 55 years and over satisfied with the government’s handling of the coronavirus, compared to 71% for the full public.

- UK: a May 7 Opinium poll finds 57% approval of the UK government’s handling of the coronavirus among adults ages 65+, compared to 49% approval overall.

There are exceptions to this pattern. In both France and Germany, approval of government handling of the pandemic is roughly the same among the elderly as it is for the general population, according to an Elabe poll in France and a Redfield and Wilton poll in Germany.

In some of the countries where the elderly give their government higher-than-average approval ratings on the pandemic, part of the reason is partisanship. In the UK, for example, older voters skew toward the Conservative party, which is in power; the higher ratings for older respondents in Britain, therefore, reflects partisan preference.

In the US, possible erosion in support for the Trump administration’s coronavirus policies may be starting to reduce support among seniors for President Trump’s re-election.

Opinions among American seniors are worth examining in some depth, as they may be experiencing a significant transition. In the 2016 US presidential election, Donald Trump beat Hillary Clinton among voters ages 65 and older by 8 points, 53-45%, according to the New York Times exit poll. Since then, older American voters have generally continued to lean toward Trump and the Republican Party.

Some polls continue to show moderately strong support for Trump among seniors, including on his handling of the coronavirus. But other polls suggest Trump may be suffering real erosion in job approval on COVID-19 from seniors. For example, a May 10 CNN poll finds that Trump’s job approval on handling the outbreak is 42-56% negative among voters age 65 and older – about the same as his rating nationwide (42-55%) on this issue.

A May 10 Morning Consult poll found higher senior support for Trump’s handling of the pandemic. In that poll, 48% of those 65 years and older give Donald Trump excellent or good marks for his handling of the coronavirus – much higher than the 37% among all registered voters. Yet even in the Morning Consult polls, Trump’s support from seniors on COVID-19 shows major erosion. On March 5, the Morning Consult polling showed Trump with a 12-point net positive approval rating from seniors on his handling of the coronavirus; by their April 26 poll, that figure had dropped to a net approval balance of 0.

It is not yet clear if this loss of approval on COVID-19 will translate into lost votes for Trump among seniors. The May 12 Economist/YouGov survey has Trump still leading presumptive Democratic nominee, Joe Biden, by 55-42% in ballot test. But a May 10 CNN poll finds Biden leading Trump among seniors by 57-42% – a significantly larger lead than Biden’s overall 51-46% margin over Trump in the same poll.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., the pandemic’s impact on home-buying) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations.

Our first eight installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through May 7, reviewed a total of 711 polls from 98 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 121 polls, covering 49 countries. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, polls reviewed here vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] This edition does not include the sections that have appeared in past weeks regarding changes in the global levels of concern about contracting COVID-19 and changes in global job approval ratings for national governments on COVID-19. Too few polls were published with such data this week for summary statistics to be reliable. We plan to resume these sections next week.

[3] Question wordings differ across countries; full wordings are available at the links for the individual surveys

[4] Survey wording: “I am worried that if the current lockdown measures are relaxed too quickly, it will do worse damage to the United Kingdom’s economy and overall health than extending them”; versus: I am worried that if the current lockdown measures are extended too much longer, it will do worse damage to the United Kingdom’s economy and overall health than relaxing them.”

[5] Survey wording: “The priority for the Government should be to limit the spread of the disease and the number of deaths, even if that means a major recession or depression, leading to businesses failing and many people losing their jobs”; versus: “The priority for the Government should be to avert a major recession or depression, protecting many jobs and businesses, even if that means the disease infects more people and causes more deaths.”

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The eight earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.