an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

Many countries are now moving to end lockdowns and re-open their economies; how do their publics feel about that? Which countries feel readier to head back to workplaces, schools, and stores – and why?

This week’s edition of Pandemic PollWatch examines how publics worldwide feel about the transition back to work, school, and social life. It is the eleventh in a series of weekly papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- Global publics feel cautious about re-opening. In most countries, people are more likely to feel their government is seeking to reopen the economy and society too quickly rather than too slowly. Strong fears of a second wave of COVID-19 later this year add to this sense of caution.

- In most countries, high shares now feel uncomfortable going to their workplaces, and outright majorities feel uncomfortable resuming most other major activities, apart from food shopping.

- Publics in most countries are particularly uncomfortable with the idea of sending children back to school.

- Countries that have built trust with their publics on battling the coronavirus tend to see greater public readiness to resume economic activity. This undercuts the idea of a strict tradeoff between health protection and economic revival, and suggests instead that countries with low public trust in their leaders on battling COVID-19 – including the US – may also pay an extra economic penalty as their publics hesitate to return to workplaces, stores, schools, and entertainment venues.

Major Insights

Publics worldwide feel cautious about the reopening process. In most countries, publics are more worried about reopening too quickly rather than too slowly. Fears of a second wave of COVID-19 add to this sense of caution.

Despite the high economic toll of the pandemic, there are few signs of global public demand to pursue economic reopening more quickly. In most countries with relevant data, publics are more worried about reopening too quickly rather than too slowly.

- Australia. May 24 Essential Research poll finds 27% of Australians believe “it is too soon to consider easing restrictions on travel and gatherings, to allow offices, shops, restaurants, other workplaces, and public spaces to start operating again”; that is almost twice the 14% who believe governments should start easing the restrictions “as soon as possible.”

- Canada. In a May 25 Leger poll, more Canadians, by 29-13% margin, believe the federal government should slow down rather than accelerate the pace of reopening (57% say the federal government should continue at its current pace); a 34-13% margin believe their provincial government should also slow down rather than accelerate reopening (with 53% saying it should continue at the current pace).

- Israel. A May 18 survey by the Guttman Center for Public Opinion and Policy Research finds that by a 39-25% margin more Israelis feel the government’s steps to restore the economy have moved too fast rather than too slow.

- UK. A May 22 JL Partners poll for the Daily Mail finds that 53-11% majority feels the government is easing the lockdown restrictions too fast rather than too slow, with 30% saying “about right.”

- US. A May 18 Quinnipiac poll finds a 75-21% majority of Americans believe “the country should reopen slowly, even if it makes the economy worse,” rejecting the alternative statement that “the country should reopen quickly, even if that makes the spread of the coronavirus worse”; as part of this, a 50-44% majority of Republicans, and supermajorities of Democrats (95%) and Independents (74%), all prefer to reopen “slowly.” A May 25 Navigator poll finds a 40% plurality in the US believe their state is moving “too quickly” to re-open, up from 35% a week earlier; only 17% say their state is moving too slowly, with 38% saying the pace is about right.

Among the countries with data on this question, Poland is a notable exception to this pattern, with a 32-14% plurality saying the government is restarting the economy too slowly rather than too fast, and 35% saying pace is appropriate, according to a May 20 SW Research poll.

One factor that may contribute to the general sense of caution is a fear that there will be a second wave of the coronavirus later this year. As noted in last week’s edition, high shares in many countries expect this to happen. A May 17 NPR/Marist poll finds that 77% of Americans are concerned about a second wave, including majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents. The Leger poll noted above finds 86% of Canadians worried about a second wave. A May 19 Ipsos poll in France finds 59% of the French expect a second wave that is as strong as the first wave, with 74% expecting a second wave that may be weaker than the first. A 92% majority of the Japanese are concerned the coronavirus “will spread again,” according to a May 17 Asahi Shimbun poll.

Feelings about the speed of reopening could change significantly as countries amass data on the post-reopening incidence of COVID-19. If there is a rise in cases in many of the first places to reopen, that could make global publics even more cautious; conversely, if there is no surge in cases or second wave, confidence about reopening may increase.

In most countries, publics remain uneasy about going to work, with outright majorities in most countries uncomfortable resuming nearly all major public activities other than food shopping.

The general sense of caution that many publics feel translates to hesitation about specific economic and social activities.

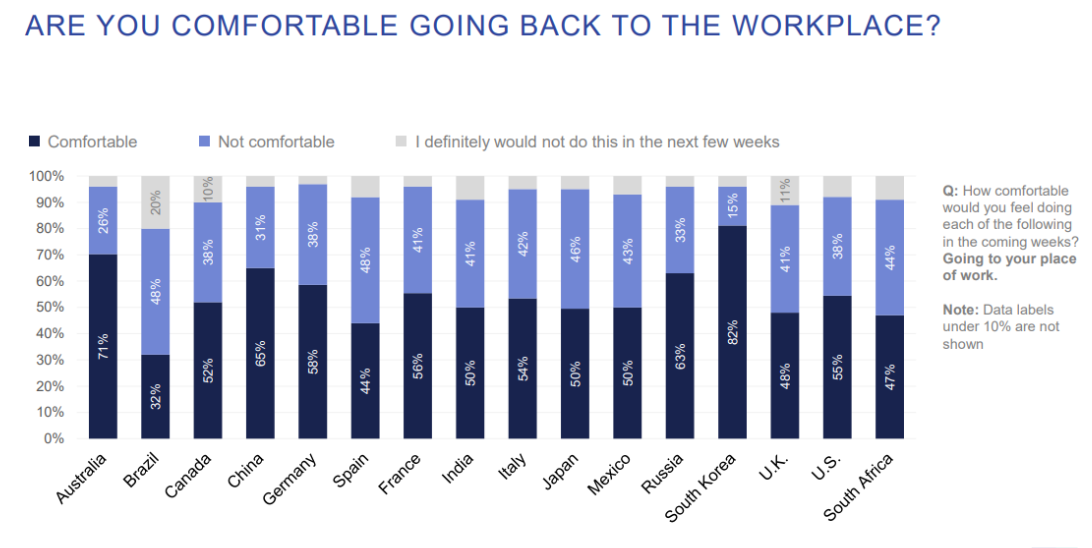

High shares not comfortable going to work. That starts with work. As Figure 1 shows, a May 10 Ipsos survey finds that, in 12 of 16 countries surveyed, majorities do feel comfortable going to their workplace (the exceptions are the UK, Spain, Brazil, and South Africa). But sizeable minority shares in each of these countries – at least 30% – feel uncomfortable; in only 4 of the countries (Australia, China, Russia, and South Korea) is there at least 60% that feel comfortable going to their workplace.

Figure 1: % who feel comfortable going to their place of work; 16 countries (Ipsos)

A May 28 Leger poll suggests the share of Americans and Canadians who feel comfortable going to work may be much lower. That poll puts the figure for the US at only 35% comfortable going to work, and only a slightly larger share of Canadians, 38%.

A May 24 Mitofsky poll in Mexico suggests slightly more comfort about returning to work in that country (although the question is not about personal confidence in returning). In that poll, a 67-26% majority of Mexicans say the government should “open factories and allow everyone to return to work.”

Majorities uncomfortable with many kinds of shopping, entertainment, and socializing. Global polls suggest that, beyond work, publics in most countries are even more uneasy about many kinds of economic, entertainment, and social activities.

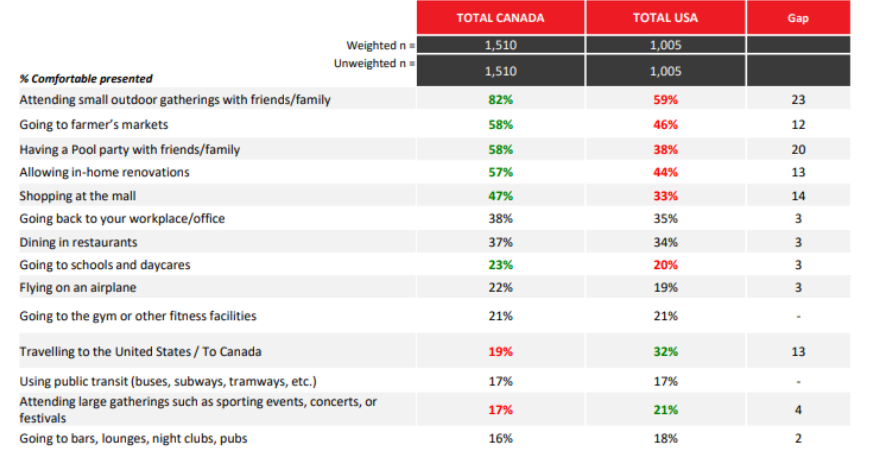

As Figure 2 shows, the Leger poll finds that most Americans and Canadians are uncomfortable with a wide range of activities, from dining in restaurants, to shopping at a mall, to using public transport. A majority of Canadians are comfortable with four activities: attending an outdoor gathering with friends and family (82% would be comfortable doing this); going to a farmer’s market (58%); having a pool party with friends and family (58%); or allowing in-home renovations (57%). In the US, there is only a majority comfortable with one of these activities – attending an outdoor gathering with friends and family (59%). (Below, we talk more about the US-Canadian disparities on these questions.)

Figure 2: % who feel comfortable with various economic/social activities; Canada and US (Leger)

In Britain, there is a similar hesitance to resume regular activities. In a May 22 JL Partners poll, fewer than half say they would be comfortable doing any of the following after lockdown ends: going to a restaurant with outdoor seating (38%); going on holiday within the UK (36%); going to a non-essential shop like a clothes store (33%); going to a pub (33%); or going on holiday abroad (18%).

In Mexico, a May 24 Mitofsky poll finds that on only one of eight activities – shopping at a food market – is there a majority that would feel comfortable, with 60% saying they would be comfortable doing that. But no more than 20% feel comfortable about many other activities, including: visiting parents and friends at their houses (18% would feel comfortable); eating in a restaurant (15%); traveling to another city by bus or airplane (9%); going to the movies (8%); visiting a sick parent in the hospital (7%); going to a packed stadium to see a sports event (3%); or going to a party or club with strangers (1%).

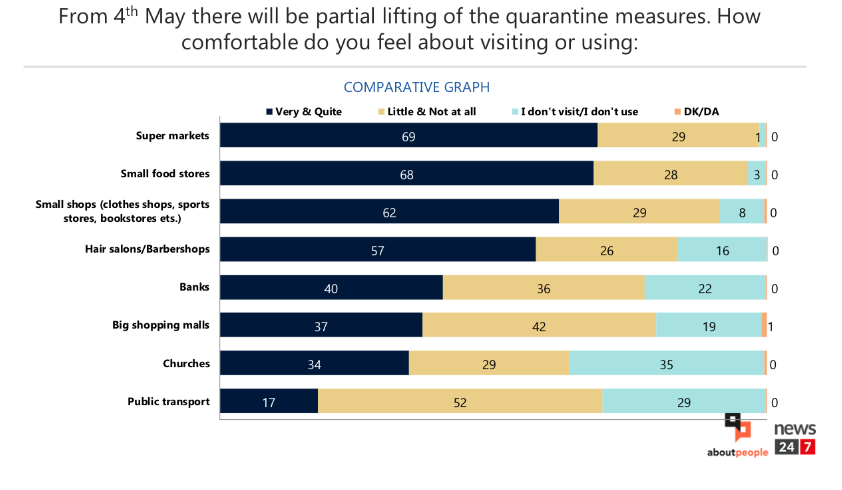

In Greece, where confidence in the government’s coronavirus policies has been relatively strong, the public feels a bit safer about resuming daily activities. A May 18 AboutPeople poll finds that majorities there would feel comfortable going to a supermarket (69%), small food store (68%), small non-food shop (62%), or beauty shop (57%). Yet even in Greece, far fewer than a majority would feel comfortable going to a bank (40%), shopping at a mall (37%), attending church (34%), or using public transport (17%).

Figure 3: % who feel comfortable with various activities; Greece (AboutPeople)

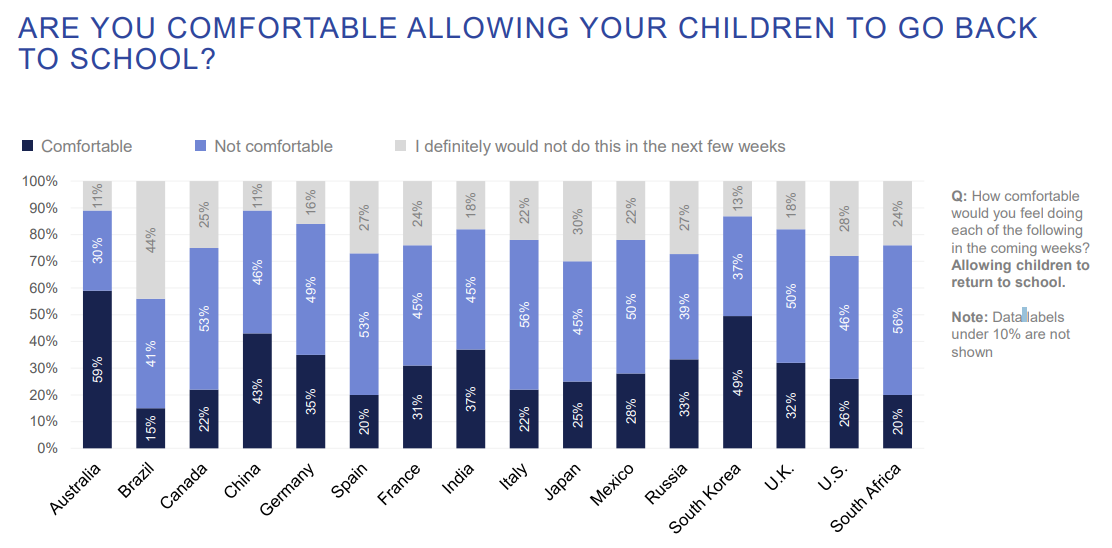

There is even deeper hesitation in most countries about sending children back to school.

The strongest hesitations, in many countries, revolve around sending children back to school. In the 16-country Ipsos poll, only one of the countries – Australia – has a majority that is comfortable sending children back to school at this point. In 13 of the 16 countries, the share comfortable sending their children back to school is under 40%. The average share across the 16 countries comfortable with their children going back to school – 31% (not weighted for population) – is 24 points lower than the average share in those countries that are comfortable going to their workplace.

Figure 4: % who feel comfortable allowing children to return to school; 16 countries (Ipsos)

In some countries, concern may be higher among people with school-age children. A May 21 ORB poll in the UK finds that people with school-age children are even more disinclined than the total public to send their children back to class. Overall, 50% of adults would not send children back to school. But the figure is even higher among parents with children under 5 years of age (59% of them would not send children back to school), and higher still for parents with children ages 6-18 (63%). However, a May 20 USA Today/Ipsos poll finds no difference in the share of parents of schoolchildren who support having their children return to school before there is a COVID-19 vaccine, relative to the full population (47% and 46%, respectively).

Countries and leaders that have failed to build trust with their publics on handling COVID-19 may wind up paying an economic penalty, as publics may hesitate to return to economic activity.

Some leaders and analysts have talked in terms of a strict tradeoff between protecting public health and reviving economic activity. The polls summarized above undercut that idea. Indeed, they suggest that countries and leaders that have lost the trust of their publics on battling the pandemic may well face an economic penalty as the reopening process begins – as their publics hesitate to return to workplaces, stores, entertainment venues, and schools.

The Leger data noted above on Canada and the US provide a good case study. The two countries are not only adjacent but also similar in many ways: big, prosperous, multi-cultural, federally structured, and sharply divided in partisan terms. Yet Canada has achieved a much higher level of public trust on handling COVID-19; according to YouGov’s tracking on this question, 78% of Canadians think their government is handling the coronavirus very or somewhat well, compared to only 43% of Americans. That huge 34-point difference was not pre-ordained due to differences of culture; in YouGov’s March 17 poll, the difference was only half as big – 17 points (63% in Canada; 46% in the US). The divergence evolved because of each public’s experience with how well their governments and leaders were handling the crisis.

Now that Canadians have more trust in their government’s handling of the coronavirus, they also feel more confident in resuming various kinds of economic activity. Out of the 14 activities Leger asks Americans and Canadians about, in terms of reopening “comfort,” there are five on which Canadians are at least 10 points more likely to say they are comfortable engaging in the activity than Americans. This includes activities that have major economic impact, like shopping at a mall or allowing in-home renovations. There is only one activity on which Americans feel at least 10 points more comfortable: 32% of Americans would feel comfortable traveling to Canada, but only 19% of Canadians would feel comfortable traveling to the US – which really counts against the US economy (i.e., it means less tourism for the US), rather than for it.

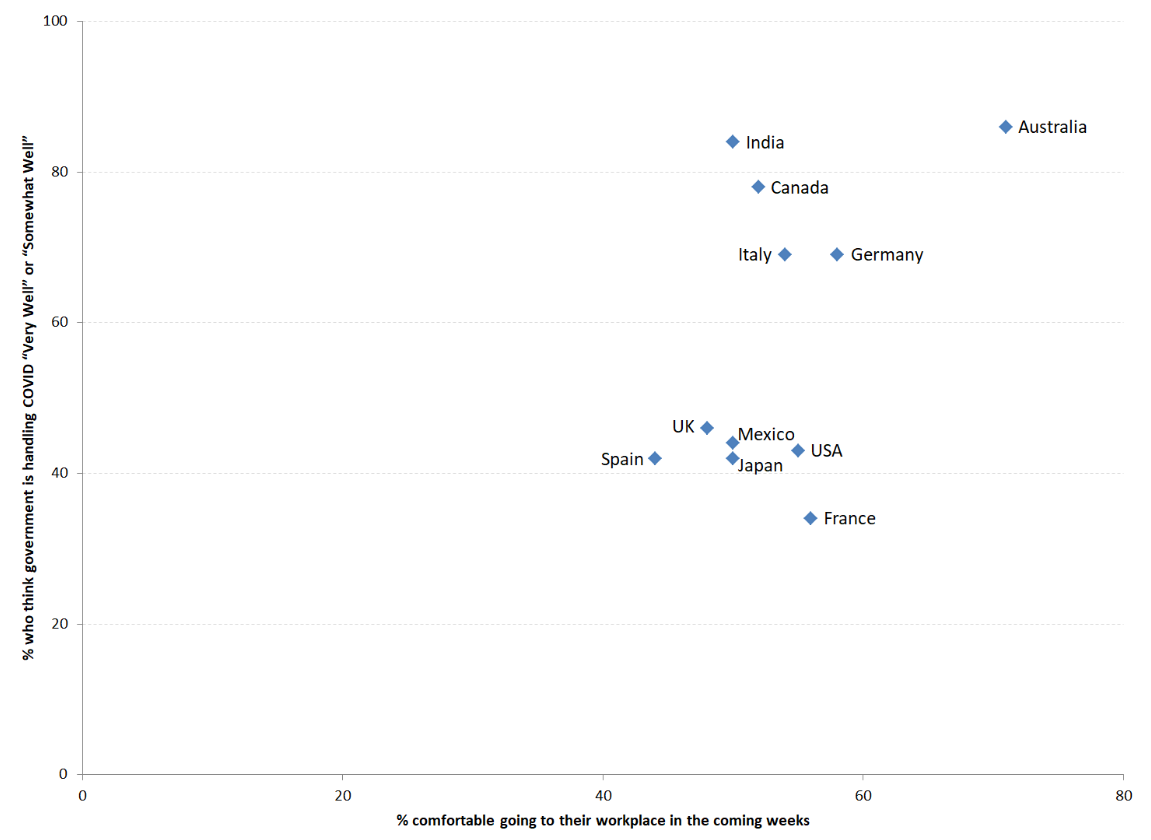

Indeed, as Figure 5 shows, there is a modest correlation (= 0.46) between confidence in a government’s handling of the coronavirus and the how comfortable its people feel going to work at this point. In countries that have achieved high public trust on their handling of the virus, such as Australia and Germany, relatively high shares feel comfortable going to work. Where trust in public leadership on coronavirus is low – as in France, Spain, Japan, and the US – lower shares feel comfortable going to work.

Figure 5: % job approval on COVID-19 (YouGov); and % who feel comfortable going to work (Ipsos)

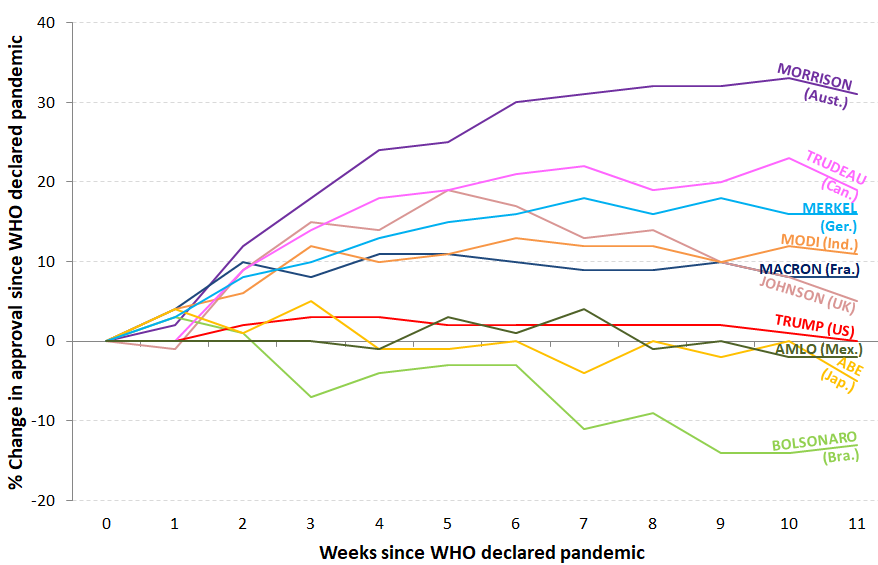

All this belies the idea that public health protection and economic revival necessarily work against each other. The analysis is also important given the wide variations in how well different world leaders have stepped up to the challenge of this pandemic. As Figure 6 shows, based on Morning Consult data (and a layout first used by the Economist), of 10 world leaders (whose countries represent over half of global GDP), 6 have seen their job approval rise since the pandemic was declared in March. Only three (Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador; Japanese PM Shinzo Abe; and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro) have seen their job approval fall. The tenth, US President Donald Trump, has the same job approval today as when the pandemic began. Those leaders who have done the most to win public confidence on the health battle may also be in better position to win the economic reopening battle.

Figure 6: % job approval for 10 global leaders (Morning Consult; layout concept from the Economist)

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., the pandemic’s impact on mental health) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first ten installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through May 21, reviewed a total of 932 polls from 99 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 95 polls, covering 36 countries, increasing the total number of geographies with reviewed public opinion data up to 100. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The ten earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.