an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

The coronavirus pandemic is now the dominant concern of publics world-wide. This the second in a series of regular papers from GQR summarizing and analyzing available data on global opinion on COVID-19.[1]

These papers are not exhaustive in analyzing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., various COVID-19-driven changes in individual behavior) not probed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of the global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls we have identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations.

The major insights in this paper:

- Concern about contracting the virus continues to rise in most places, often not fully correlating with known in-country infection rates.

- Publics in many places are giving leaders higher marks for their handling of COVID-19 than for their job performance overall.

- Despite the comparatively high approval ratings for handling the pandemic, early polling in several countries suggests only slight gains for leaders’ likely vote outcomes in their next elections.

- The pandemic is affecting the work of the polling industry, like all other businesses; we offer some observations about how it is affecting modes and reliability of global opinion research.

Major Insights

Concern about contracting the virus continues to rise in most places

A YouGov tracking survey last updated March 25 covering 25 countries plus one territory (Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Norway, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, UAE, US, UK, Vietnam) finds the share who say they are “very” or “somewhat scared they will contract COVID-19 (coronavirus)” has moved up in 17 of the geographies, and is steady (no change or a change of at most one point) in 6. Only two countries registered a drop in fear levels: Japan (down from 66% on March 17 to 63% on March 24) and Italy (74% on March 19 to 72% on March 25). Thailand and Indonesia saw declines in fear levels earlier, but they have now moved back up. Time series data was not available for Vietnam.

In over half of the 26 geographies, the share that are very or somewhat scared is over 60%. Among these geographies, France shows the fastest rise in fear, more than doubling from 30% on March 10 up to 61% on March 20.

Fear levels continue not to correlate fully to incidence of the disease (although incidence data may suffer from flaws in testing and reporting of cases). For example, Malaysia has the highest level of fear among these 26 YouGov geographies, with 90% very or somewhat scared of contracting COVID-19; yet it has only 68 reported cases per million people. In Italy, by contrast, with about 1,300 cases per million, the fear level is somewhat lower, at 72% very or somewhat scared. Across the sea in Greece, there are only 83 cases per million people, but a March 23 NEWS24/7 poll finds that 92% of Greeks are “very” or “quite” concerned about the coronavirus—up 20 points since March 9.

Many leaders seeing relatively strong job approval on handling COVID-19

Some of the biggest questions about the coronavirus pandemic involve its global impact on politics. Will the pandemic be a boost to incumbent leaders as voters rally around their leaders in a time of crisis? Or will it more frequently result in ruling parties and leaders facing defeat, as voters register their anxiety over dire health and economic conditions?

The evidence at this point remains inconclusive, in part because there have been few elections since the start of the outbreak. Indeed, elections have been postponed in many places due to health concerns, including in parts of the US and Spain, as well as nation-wide elections in Bolivia, the UK, France, Serbia, North Macedonia, and Italy (a referendum).

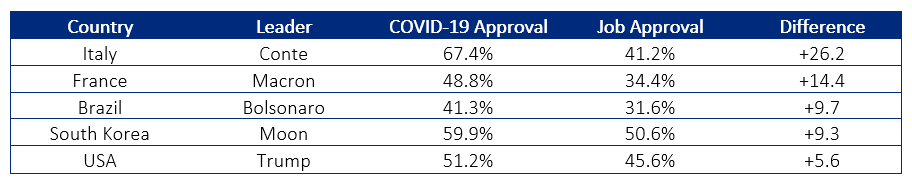

The early evidence is that the crisis is having a modest upward impact on job approval ratings of leaders and governments globally, although the results are uneven. As the following table[2] suggests, in most places where such data is available, leaders are getting higher scores for their job in managing the COVID-19 crisis than for their overall job as national leader:

Despite these relatively favorable job performance ratings on COVID-19, leaders may be gaining less on political support.

There are also early signs that relatively positive evaluations of government performance on the pandemic may not be greatly affecting the re-election chances of the corresponding leaders. Just as there appears to be relatively less improvement on overall job performance for key leaders, compared to their performance on handling COVID-19, there is also relatively little improvement on more direct indicators of political support, such as estimates of likely vote share.

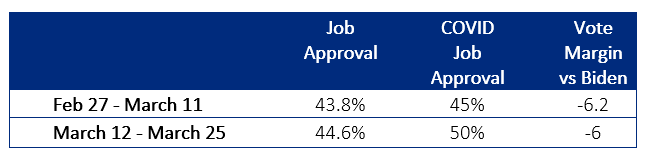

In the US, as the table below suggests, President Trump saw a notable rise in his job approval in handling COVID-19 between early and late March – a full 5-point rise. Averaging across available polls, his job approval rating on COVID-19 is now 50%. That 50% approval rate is more than 5 points above his job approval rate overall (now at an average of 44.6%), and the increase in his COVID-19 job approval rate is greater than the rise in his overall approval rate, which has moved up only about a point. During this same period, Trump’s head-to-head ballot performance against his likely opponent, former Vice President Joseph Biden, is virtually unchanged, moving up only a quarter point.

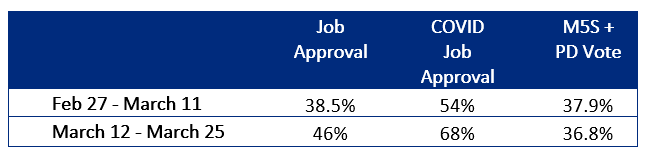

In Italy, Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte has seen a notable rise in both the overall confidence in his government and his job approval on COVID-19. Between the first and second half of March, public confidence in Conte’s government rose from approximately 38% to 46%. Job approval on handling COVID-19 climbed even more sharply—14 points between the first and second half of March. But Parliamentary vote intention has not seen a similar bump in the same period. Though PM Conte is an independent, he has formed a government with representatives from the Democratic Party and the Five-Star Movement. Neither party has seen any significant change in their vote share during this period, with their combined vote actually falling just under a point.

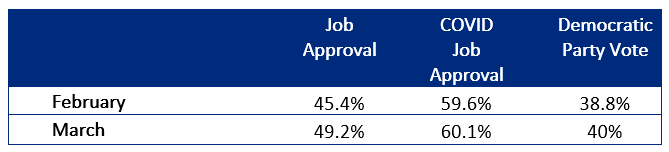

In South Korea—a country where the virus emerged earlier than in the US or Italy—President Moon Jae In has also seen increases in his personal approval rating. Across the month of February, his job approval rating averaged about 45%. During March (up to the time of publication), his job approval rating rose to an average of about 49%. While his government’s approval rating for handling COVID-19 is higher than his personal job approval, as noted above, it rose less than a point since February. However, despite a COVID-19 job approval rating that is above his overall job approval rating, and despite the rise in the President’s overall job approval rating, support for his Democratic Party has moved up only slightly, rising just about a point between February and March.

There are many caveats to this analysis. It only looks at three countries. Those countries are in no way random or representative. The evolution of public opinion on such questions is still in the early days in all countries. And it is likely that the pandemic will have different impacts on different leaders, depending on how well their voters believe they handled the crisis. Even so, these early indicators suggest that there may be some disconnect between how publics respond to leaders’ efforts on the pandemic, on one hand, and their willingness to vote for governing leaders and parties, on the other.

The COVID-19 pandemic has deeply affected the polling industry, although quality polling continues in most places.

As we summarize available global research on COVID-19, it is worth noting how the pandemic has affected opinion research itself, in part so that there is a sense of how accurate polls are during this unique period.

The pandemic is confronting opinion research, like nearly all industries, with major challenges to its standard operating procedures. Some forms of research, particularly in-person focus groups, are no longer viable. In-person interviews, including techniques such as mall intercepts, have also been curtailed. Some forms of qualitative research continue, such as online focus groups. But the new limitations on qualitative research are troubling, since qualitative insights are often crucial to informing relevant polling questions.

Surveys, by contrast, continue to field in most locations – as the wide array of polling results summarized in this report suggests. In many developed countries, most major surveys were already conducted by phone or online, so there has been relatively little disruption in the flow of polling. Major calling houses have software that allows interviewers to call from their homes rather than from calling centers, which enables phone surveys to continue.

The main places where reliable polling has suffered is in developing or transitional countries, where face-to-face surveys have usually been the gold standard. In many such countries, curfews, quarantines, and other restrictions are making such research impossible. In a March 13 report, one of the largest international research companies[3] reported they were no longer able to fully conduct face-to-face surveys in a third of the 90+ countries in which they conduct face-to-face surveys.

As a result, in many developing and transitional countries, there has been a shift to phone or online polling. Yet lower internet penetration rates and limited phone databases in many of these places mean such polls have more limited reliability. For example, only about 1 in 3 countries have internet penetration over 70%. Online poll results from such countries, therefore, may be under-representing the views of rural, poorer, older, or women demographic groups, depending on the country.

Another question regards response rates – whether the pandemic is making it harder to reach respondents. In our firm’s own US surveys, we have actually seen a slight increase in response rates. It is likely that upticks in pandemic-related teleworking, free-time, and loneliness, are all helping to partially mitigate the decades-long industry trend toward worsening response rates in phone surveys.

[1] Our first installment of Pandemic PollWatch, on March 19, reviewed 58 polls from 40 countries and territories. This edition scans an additional 64 polls from 32 different geographies. In all at this point, we have reviewed polling data from a total of 45 geographies (since there is geographic overlap between the two weeks’ analyses). Links to all new polls reviewed for this edition are listed in the Appendix. The Appendix in the first edition includes links to all the earlier polls reviewed. As the Appendix notes, polls reviewed here vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] Values are an average of up to last 5 polls, with fewer polls averaged where fewer were available.

[3] Ipsos. Impact Assessment of COVID-19. 13 March 2020.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Australia

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- China

- Denmark

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Greece

- Hong Kong

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Italy

- Japan

- Kenya

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Norway

- Poland

- Philippines

- Romania

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Slovenia

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Thailand

- Taiwan

- Turkey

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Vietnam

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The polls reviewed for this edition of Pandemic PollWatch (with links in all possible cases) are listed below. Please refer to the previous edition of Pandemic PollWatch for a list and links for all previous polls reviewed.

Brazil

- Panará Research Institute; 18-21 March 2020; 2,020 adults; telephone; link

- XP Investimentos; March 16-18, 2020; 1,000 adults, telephone; link

- Datafolha; March 18-20, 2020; 1,558 adults; telephone; link

Canada

- Research Co.; March 21-22, 2020; 1,000 adults; online; link

France

- Elabe; March 23-24, 2020; 1,003 adults; online; Link

- Opinion Way; March 20-21, 2020; 1000 adults; online; link

- YouGov; March 19-20; 1,001 adults; online; link

- Odoxa; March 18-19, 2020; 1,005 adults, online; link

- YouGov; March 17-18, 2020; 1,004 adults; online; link

- Opinion Way; March 11-12, 2020; 1,013 adults; online; link

Georgia

- ACT; March 12-13, 2020; 124 Georgian company management representatives, telephone; link

Germany

- Institute Forsa; March 23-25, 2020; 1,502 adults; not specified; link

- INSA Meinungstrend; March 18, 2020; link

Greece

- About People; March 22-23, 2020; 843 adults; online; link

India

- Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry; March 15-19; 317 companies; link

Italy

- Ixe; March 23-24, 2020; 1,000 adults; CATI, CAMI, CAWI; link

- Demopolis; March 22-23; 1,500 adults; not specified; link

- Tecnè; March 19-20, 2020; 1,000 adults; CATI, CAWI; link

- Demos; March 16-17, 2020; 1028 adults; mixed mode CATI, CAMI, CAWI; link

- SWG Observatory; March 11-13, 2020; 800 adults, telephone; link

Kenya

- TIFA Research; March 15-21; 1,000 adults; telephone; link

Mexico

- Enkoll; March 14-16, 2020; 1,000 adults over 16; telephone; link

- Grupo Reforma; March 4-6, 2020; 400 adults; telephone; link

New Zealand

- Utting Research; March 22, 2020; 3,133 adults, telephone; link

Poland

- IBRIS; March 23, 2020; 1,100 adults; telephone; link

- United Surveys; March 16, 2020; Survey size not available; link

South Korea

- Real Meter; March 20, 2020; 7259 adults; telephone; link

- Real Meter; March 18, 2020; 7,293 adults; telephone; link

- Gallup Korea; March 17-19, 2020; 1,000 adults, telephone; link

- Real Meter; March 13, 2020; 12,160 adults; telephone; link

Taiwan

- Yahoo News; March 17, 2020; link

UK

- JL Partners; March 24; 2110 adults; online; link

- YouGov; March 24; 2972 adults; online; link

- Ipsos; March 20-23; 1,079 adults; online; link

- Survation; March 13-17, 2020; 3,007 adults, online; link

USA

- Washington Post/ABC News; March 22-25, 2020; 1,003 adults, telephone; link

- YouGov; March 23-25; 1,000 adults; online; link

- CIVIQS; February 25-March 25, 2020; 11,616 responders; online;link

- Navigator; March 22-25, 1,003 Registered voters, online; link

- The Economist/YouGov; March 22-24, 2020; 1,500 adults; online;link

- Navigator; March 21-24, 2020; 1,012 Registered voters, online; link

- Ipsos/Reuters; March 18-24, 2020; online; link

- YouGov; March 21-23; 1,000 adults; online; link

- Navigator; March 20-23, 2020; 1,038 Registered Voters, online; link

- Monmouth; March 18-22, 2020; 851 adults; telephone; link

- Morning Consult/Politico; March 20-22, 2020; 1,996 Registered Voters; link

- Harris; March 21-22, 2020; 2,023 adults; online; link

- Gallup; March 20-22, 2020; Gallup panel; link

- Monmouth; March 18-22, 2020; 754 registered voters; telephone; link

- CIVIQS; February 25-March 22, 2020; 10,054 Responses; link

- College Reaction; March 21; 965 Panelists; online; link

- Morning Consult; March 17-20, 2020; 1796 registered voters; online; link

- ABC/Ipsos; March 18-19, 2020; 502 adults, online; link

- Emerson; March 18-19, 2020; 1,110 Registered voters, IVR and online; link

- SurveyMonkey/Fortune Magazine; March 16-17, 2020; 2,690 adults; online; link

- Newsweek; March 16; 15 economists; link

- Russell Research; March 13-16, 2020; 1,012 adults; online; link

- Survey 160; March 13-16, 2020; 609 respondents; SMS; link

- Politico/Morning Consult; March 13-16, 2020; 1,986 Registered voters, online; link

- AP/NORC; March 12-16, 2020; 1,003 adults, online and telephone; link

- Pew Research; March 10-16, 2020; 8,914 panelists; online; link

Multi-Country