an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

This is the sixth in a series of weekly papers from GQR summarizing and analyzing available data on global opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. The major insights in this paper:

- For the first time, global polling now shows a majority of countries experiencing a drop in the share of their publics who are concerned about contracting COVID-19. Countries with declining concern this week outnumber those with rising concern by almost a 10:1 ratio, with an average drop of slightly over 6 points in the percent of people in each country who are concerned about contracting the disease. The numbers this week are a mirror image of the picture in late March, when global concern was soaring.

- Government job approval ratings on handling COVID-19 are now steady in a majority of the countries with such data; but in the remainder, countries with rising ratings outnumber those with falling job approval by about 4:1. COVID-19 job approval rates for President Trump have declined gradually over the past two weeks, which is a different pattern than in most countries with comparable data.

- A key variable in public perceptions of the coronavirus crisis is how people use and perceive the news media. Global polling shows that publics worldwide are consuming more news during the pandemic, mainly relying on television for information about COVID-19, and most trust the media more on average than in the past. There is wide variation from country to country, however, on whether people feel the media has exaggerated the threat from COVID-19, with some evidence that publics are less likely to feel the media has exaggerated the threat in countries with more COVID-19 cases per capita.

Major Insights

For the first time, there is a sharp decline in global public concern about contracting COVID-19

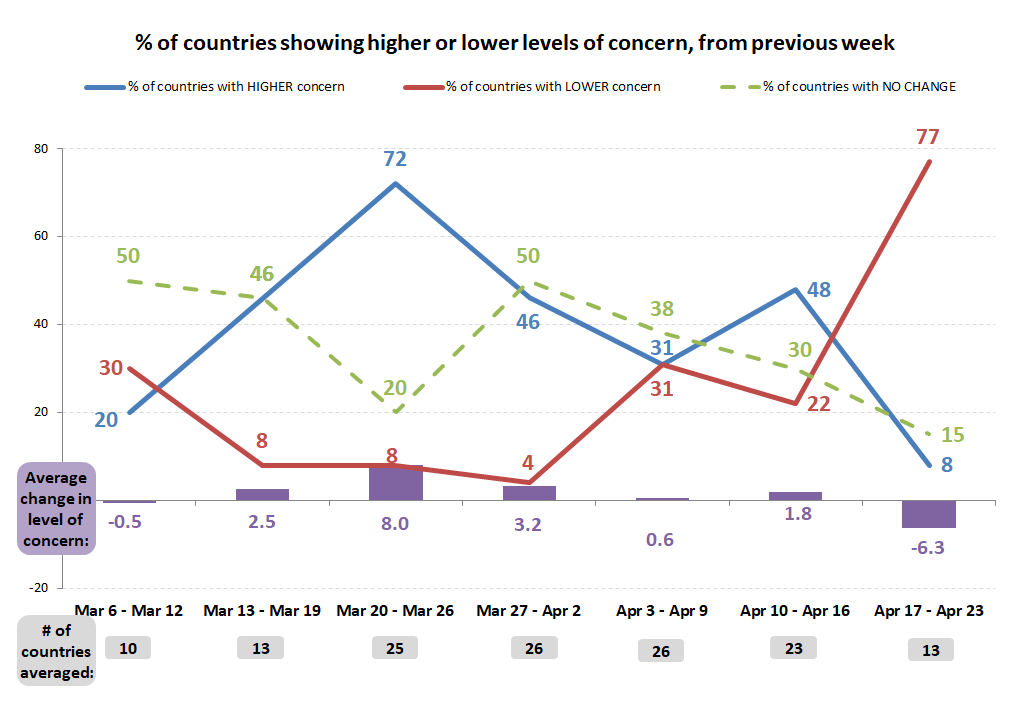

This week’s global polling data marks the first time since the start of the pandemic that a majority of countries saw drops in the share of people who are concerned about contracting COVID-19. As Figure 1 shows, over three-fourths of all countries with such data – 77% — show a notable drop (at least 3 percentage points) in the share of their public concerned about contracting COVID-19. [2] Only 8% of the countries show a notable rise in such concerns. The average drop in concern this past week, across countries with such data, is a little over 6 points.

These figures are virtually a mirror image of the data from the week that ended March 26. At that point, 72% of the countries showed notable increases in concern about contracting COVID-19, compared to just 8% showing a decline in concern.

Figure 1: % of countries showing higher or concern levels

Global ratings for job approval on handling COVID-19 mostly stable globally, declining slightly in the US

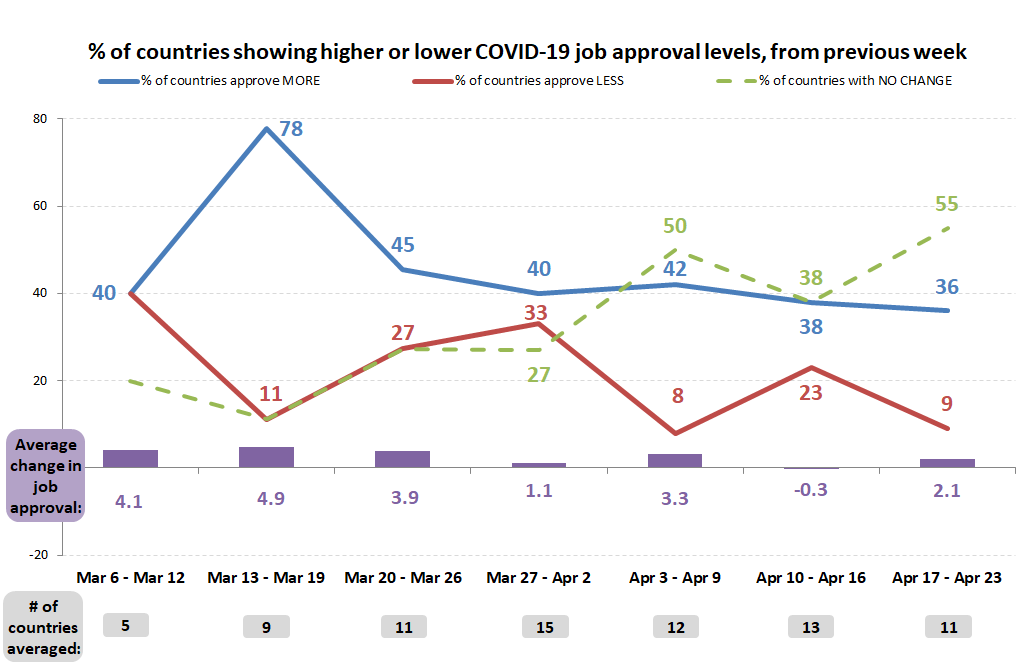

As worldwide public worries about the disease abate somewhat, there is a general pattern of stabilization in the job approval ratings governments get on their handling of COVID-19. Overall, as Figure 2 shows, a 55% majority of countries with such data show no real change in their COVID-19 job approval ratings (meaning a change of less than three percentage points).

Of the countries that do show changes, more countries show rising approval ratings. In all, 36% of the countries show COVID-19 job approval ratings rising by at least 3 points, compared to only 9% of the countries showing a notable decline in their government’s COVID-19 job approval ratings.

Figure 2: % of countries showing higher or lower COVID-19 job approval levels

In the US, COVID-19 job approval ratings for President Trump dropped gradually (although less than 3 points per week) over the past two weeks. Only three other countries with comparable tracking data – Japan, Spain, and Greece – show any drops in COVID-19 job approval; most show at least some degree of improvement.

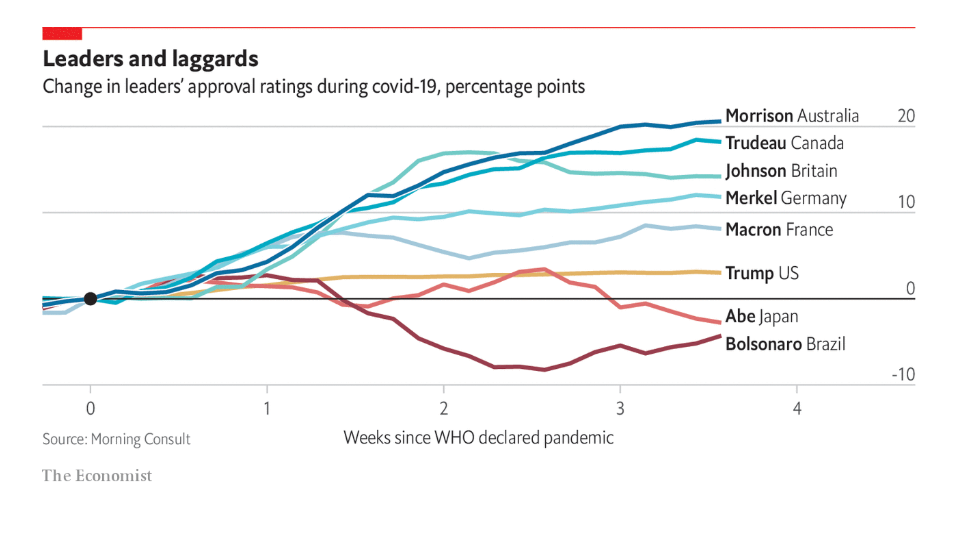

The US is also notable on the recent changes in overall job approval for the country’s leader. As revealed by Figure 3, from the Economist, based on Morning Consult data, Trump has seen less improvement in his overall job approval than many other world leaders, relative to their approval ratings when the pandemic was declared.

Figure 3: Change in overall job approval of Trump and other world leaders

COVID-19’s impact on trust in the media: people consuming more news; trusting the news media more; most relying on TV; US is uniquely polarized.

A key variable in public perceptions of the coronavirus crisis is how people use and perceive the news media. Global polling shows some broad consistencies in worldwide reactions toward the news media, but also a few differences.

First, there is a global surge in news consumption. An April 2020 Reuters Institute/YouGov study of the US, UK, Germany, Spain, Argentina, and South Korea finds a surge in news watching in all six countries. Recent polling shows increased news consumption in other countries as well. For example, an April 14 Whyte/Dedicated polling institute study in Belgium finds 66% of residents seeking out news more often than normal to find information on COVID-19. A March 27 poll in New Zealand commissioned by Spinoff/Stickybeak finds 25% of all respondents checking the news at least hourly to get updates on the coronavirus. In none of the global public polls is there a case of a country’s public saying it is consuming news less often.

Second, publics worldwide are generally relying on television for their news, and trusting television most among news sources. An April 13 Kantar survey of all the G-7 countries found TV news was the most trusted source of information about the coronavirus outbreak in 4 of the countries (Japan, Italy, Germany, and France), with TV news tied with government sources in the UK, and in second place in the US (behind “my doctor or health care provider”) and in Canada (behind government sources). Social media reliability was in single digits in all seven countries.

Other US polls also suggest Americans are getting most of their information on the pandemic from television. An April 14 Economist/YouGov survey finds that 55% cite either national broadcast news, cable news, or local television news as their primary source of news at this point, far above social media (14%), other Internet (14%), newspapers (9%), or radio (4%). A March AP/NORC survey shows that reliance on social media for news among younger Americans, ages 18-29, is more than twice as high as the national average, but still runs behind this group’s reliance on traditional news sources.

The general pattern of reliance on television is the same in most of the global polling.

- For example, an April 3 Datafolha poll in Brazil finds 81% saying TV is their main source of information about COVID-19 (followed by 29% turning to social media, 28% looking to online news sites, 11% relying on “the Internet” in general), but only single-digit levels rely on newspapers or relatives and friends.

- A March 16 Ipsos poll found that the Spanish public is getting most of their news from television, with Internet, social media, newspapers, and radio following behind; although it also found that the public trusted radio slightly more than television as a source of information about coronavirus.

- A March 21 Vetenskap & Allmanhet (Public & Science) poll In Sweden found that television was by far the leading source of information about COVID-19, relied on by 76% of respondents, with only 12% relying on government agency information, and 2% turning to social media.

- A March 14 SESRI/Qatar University survey found that television was also the main source of information about the coronavirus among Qataris and white-collar expatriates working in Qatar, although blue-collar expats in Qatar relied most on Facebook and word of mouth to get such news.

One notable exception regarding the dominance of television as an information source on COVID-19 is in sub-Saharan Africa. An April 9 GeoPoll survey of 12 sub-Saharan African countries finds that television is the main source of information about COVID-19 overall across this set of countries; but social media is the dominant information source in Benin, Nigeria, and Zambia; and radio is the dominant source in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda. It may be that social media and radio are more important information sources on COVID-19 in some other developing countries as well.

Third, while social media and other parts of the Internet are not the main source of news about the pandemic in most places, they are playing key roles in providing information and shaping attitudes. While virtually all polls find higher use of online news sources among the young, it also appears the young are using different platforms. For example, the Reuters/YouGov study finds that between 24-49% of people ages 18-24 in five of the six countries they studied had accessed Instagram in the last week for news about coronavirus

In addition, search engines may be playing a particularly strong role in providing information about the pandemic. The Reuters/YouGov poll finds that search engines, and particularly Google – or “Naver” in South Korea, the leading search engine there – are considered more trustworthy sources of news and information about coronavirus than social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

Fourth, trust in the media is up in most countries where polls have tracked this question. The Reuters/YouGov study found that majorities in all six countries rated news organizations as relatively trustworthy, whereas in 2019 only a minority in each country said they trusted most news most of the time (the questions were somewhat different between the two time periods). In the US, although trust in the news media is about evenly split (and differs very strongly along partisan lines), an April 10 Ipsos survey finds that trust in the news media is up 9 points from a month earlier – up from 39% to 48% – with bigger trust gains for the news media than for President Trump, Vice President Pence, the WHO, and Congress, and tying with the CDC (although governors gained more on trust, and remain more trusted than the news media). Rising trust in the media in the US is particularly notable against the backdrop of a decades-long decline on this metric, according to Gallup data.

There are some at least partial exceptions to the general trend. One is Australia, where polling by Essential finds that the share that say “I trust the media to provide honest and objective information about the COVID-19 outbreak” moved up 16 points, from 35% to 51%, between March 22 and April 6, but then moved back down to 42% by April 13. The latter figure is still higher than the March starting point, however. Similarly, the April 3 Datafolha survey in Brazil shows a very slight fallback in trust levels for TV news (down from 86% to 83%) and newspapers (down from 82% to 79%). In Norway, a March 19 Statista poll finds trust levels up relative to a year earlier for television news outlets, but down for regional and business newspapers. In the UK, there has been some recent public criticism (and parody) of the performance of certain journalists and their pursuit of the coronavirus story, and there are some signs trust in parts of the British media may be declining.

Fifth, publics worldwide mostly appear to be using what they hear from the media to differentiate between true and false information about the pandemic; but confidence in the accuracy of the news media varies across countries and outlets. A regression analysis in the Reuters/YouGov study of six countries found that, in every country except Argentina and Spain, people who relied more on news organizations for information about the pandemic (and controlling for other variables) had significantly higher levels of knowledge about the outbreak. They also found no evidence that greater reliance on social media led to less knowledge about the outbreak.

The study also found that people in the six countries mostly were able to differentiate between true and false information about the pandemic. For example, super-majorities in all six countries knew that older people are more susceptible to becoming seriously ill from coronavirus, and also knew that eating garlic was not effective in preventing COVID-19 infection. One exception was the idea that “coronavirus was made in a laboratory,” rather than arising naturally. There were only bare majorities in the UK and Germany who knew this was false; in the US, Spain, South Korea, and Argentina, only pluralities labeled this idea as false rather than true, with the levels nearly tied in both Spain and Argentina.

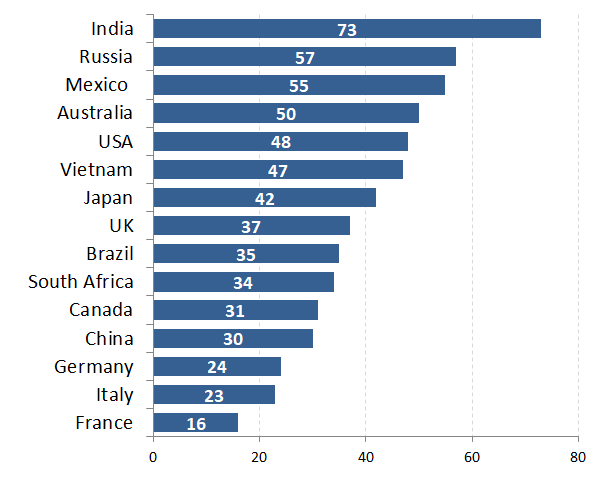

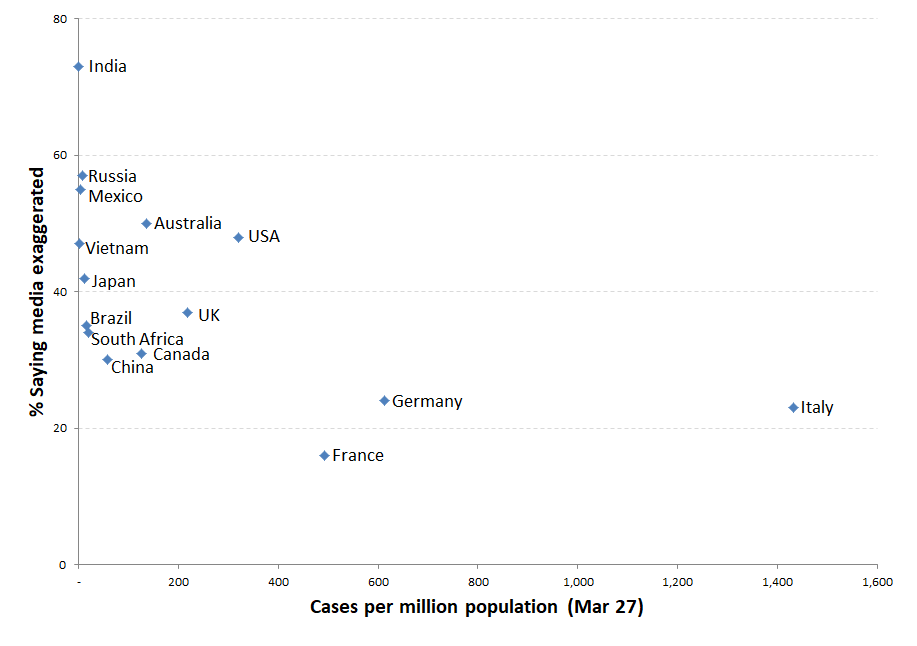

The Reuters/YouGov study found that on average only 32% of publics in those countries felt the news media had exaggerated the pandemic (although that was higher than the share—18%—who felt their national government had exaggerated the threat). But as Figure 4 shows, global late-March polling by Ipsos finds a great deal of national variation on perceptions of whether the media have exaggerated the outbreak. The share that feel this way runs from highs of 73% in India, 57% in Russia, and 55% in Mexico, to lows of 30% in China, 24% in Germany, 23% in Italy, and 16% in France.

Figure 4: % saying media in their country have exaggerated the COVID-19 threat (Ipsos data)

As Figure 5 shows, the countries with stronger feelings that the media is exaggerating the COVID-19 threat also tend to have lower incidence of the disease. Although the correlation is not intense (0.55), it suggests that public may be less likely to feel the media are exaggerating the threat as the disease spreads in their countries.

Figure 5: % saying media exaggerated the threat vs. COVID-19 cases per million population

There are also important differences across news sources, in terms of whether people trust the accuracy of the information they are receiving, with social media getting much lower trust scores than traditional news organizations. As the Reuters/YouGov study concludes: “In every country [of the six they studied], many more people find news and information on coronavirus from news organisations trustworthy than say the same about things they find on social media. Across the six countries, the ‘trust gap’ between news organisations and social media is, on average, 33 percentage points.”

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., changes in consumer confidence as a result of the pandemic) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations.

Our first five installments of Pandemic PollWatch, on March 20 and 27, and April 2, 9, and 16 reviewed a total of 420 polls from 87 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling on Hong Kong). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 99 polls, covering 50 countries and geographies, increasing the total number of geographies with reviewed public opinion data up to 96. Links to all new polls reviewed are listed here. The Appendices for the five prior editions, all available here, include links to all the earlier polls reviewed. As the Appendix notes, polls reviewed here vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] For both Figures 1 and 2, data only compiled for countries having week-on-week public polling on the question shown. Countries only counted as showing an “increase/decrease” if the week’s change is at least 3 percentage points. Average for change in level of concern is not population-weighted across countries. Question wordings may differ somewhat across countries and weeks. In both Figures 1 and 2, the data from previous weeks has been revised slightly from last week’s edition of PollWatch to reflect late-arriving data.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Denmark

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Estonia

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- North Macedonia

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The polls reviewed for this edition of Pandemic PollWatch (with links in all possible cases) are listed below. The four earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.