The global picture of the coronavirus pandemic now looks like a split screen: new incidence numbers have fallen in much of the world, while in some other places—including the United States—they are soaring. With some countries pursuing successful strategies against the virus, while others fail to, how are levels of concern and other pandemic-related attitudes changing among global publics?

This edition of Pandemic PollWatch provides an updated summary of global polling on public concern about the pandemic, with a particular examination of how publics worldwide feel about wearing face masks and taking other precautions.

This is the sixteenth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- More than 4 months into the pandemic, the coronavirus remains the top concern of publics worldwide, on average; but there are signs that the strength of that concern has abated somewhat.

- As the pandemic evolves, fears of contracting COVID-19 show strong regional variations, as different countries and regions achieve different rates of success in combatting the pandemic. Asian-Pacific countries are generally most fearful of contracting the disease, European countries are generally the least fearful, and countries in the Americas are generally in between.

- Despite some easing of concern about the pandemic, approval ratings for governments’ handling of the pandemic have fallen worldwide in recent weeks.

- One of the most dramatic changes in global opinion regarding the pandemic has been with regard to wearing face masks. In March, few countries outside Asia had majorities wearing masks; but now, few outside Scandinavia lack a majority who report wearing masks. Majorities across many countries endorse making it mandatory to wear masks. In the US, while majorities overall endorse the wisdom of wearing masks, the Trump administration’s equivocal stance on mask-wearing has fostered notably partisan patterns of support for mandating mask-wearing.

- The Trump administration’s resistance to scientific guidance takes place against the backdrop of a rise in faith in science among the American public, relative to six years ago; this may partly explain why the public has steadily lost faith in Trump’s handling of the pandemic.

Major Insights

More than 4 months into the pandemic, the coronavirus remains the top concern of publics worldwide, on average; but there are signs that the strength of that concern has abated somewhat since the early months of the outbreak.

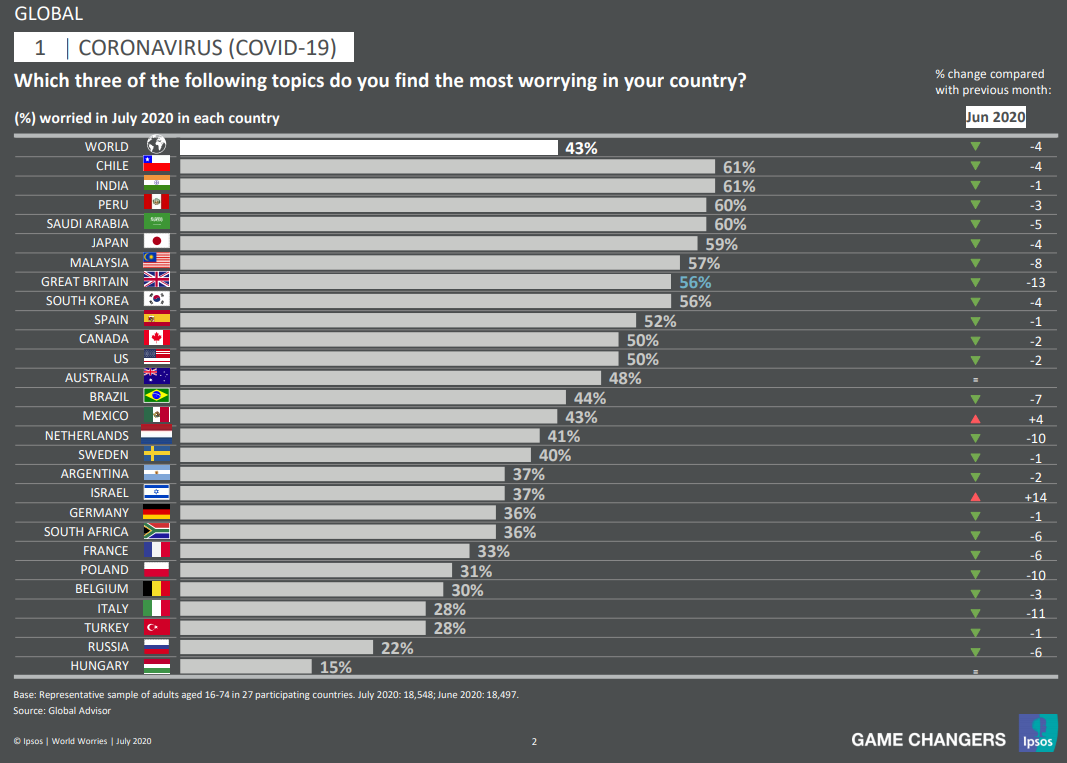

An Ipsos “What Worries the World” poll of 27 countries in July finds that coronavirus is still the top concern, on average, across these countries. But it is only the #1 concern in 11 of the countries now, whereas in April it was the top concern in 24 of the 28 countries surveyed.

As Figure 1 shows, in 23 of the 27 countries surveyed in July, the share who list coronavirus as their top concern is down – concern only rose in 2 of the countries, Mexico and Israel – and the drop across all countries (not population weighted) averages -4 percentage points.

Figure 1: % in each country that list coronavirus as the #1 concern facing the country (Ipsos)

One sign from Europe about the persistence of strong concern over the pandemic comes from attitudes toward the EU budget. Despite the fact that Europe has generally reduced the incidence of new COVID-19 cases, a late June Kantar survey of the 27 EU member states finds that Europeans still most strongly favor spending the EU budget on public health, with 55% picking it as one of their top areas of focus, from a list of 12 options. “Economic recovery and new opportunities for business” trails 10 points behind, at 45%.

Health continues to dominate economic concerns in other regions as well. A June 1 Kantar survey of the G7 countries finds that in 6 of the 7 countries (Italy is the only exception), more people say their government is putting “too much emphasis on protecting the country’s economy, and not enough on protecting people’s health,” as opposed to the inverse. This sentiment is strongest in the US, where 48% say the government is not doing enough to protect people’s health, compared to only 21% who say the government is not focusing enough on the country’s economy (22% in the US says the government has the balance “about right”).

As the pandemic evolves, fears of contracting COVID-19 show strong regional variations, as different countries and regions achieve different rates of success in combatting the pandemic.

As the incidence of the disease takes different paths in different places, public concerns about contracting COVID-19 increasingly show regional variations. The variations reflect both the success of the governments in those regions in combatting the disease, and differences in when the disease peaked – early, late, or (as in the US) more than once.

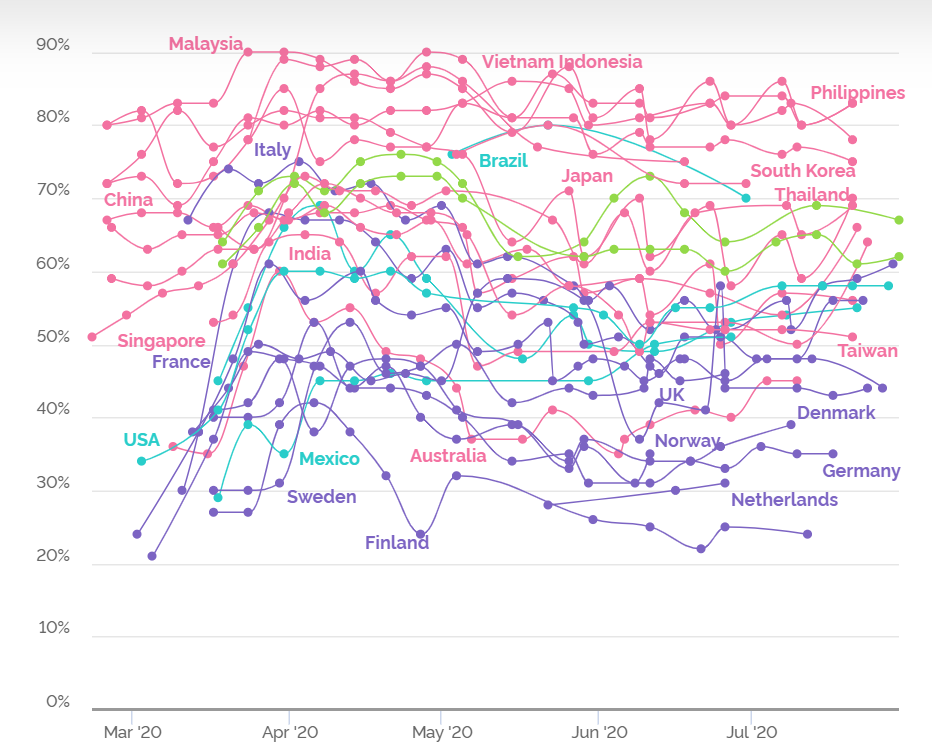

As Figure 2 reveals, data from YouGov, which tracks levels of concern about contracting COVID-19 across dozens of countries, shows distinct regional variations:

- Asia-Pacific. Concerns generally have been and remain highest in Asian countries, many of which (e.g., India) are still seeing COVID-19 case numbers rise. Across the 13 Asia-Pacific countries in the YouGov tracking, the average share who are very/somewhat scared of contracting COVID-19 is 68%.

- Europe. Concerns are generally lowest in Europe, which has significantly “flattened the curve” on COVID-19 cases. Of the 10 European countries in the YouGov tracking, only two (Denmark and Norway) have seen rises in concern of more than 2 points in the most recent tracking period. The average level of very/somewhat scared across the 10 European countries tracked by YouGov is 42%. In the Ipsos data in Figure 1, all four of the countries with the biggest, double-digit drops in the share that list coronavirus as the #1 concern are in Europe (UK, Netherlands, Poland, Italy). Effective health policies have created a less fearful opinion environment.

- The Americas have tended to fall in between, with the level of concern in the US at 58%, higher than every country in the region except Brazil (70%). The average for the four Western Hemisphere countries surveyed by YouGov is 59%.

Figure 2: % who are “very” or “somewhat scared” that they will contract COVID-19 (YouGov)

Despite some easing of concern about the pandemic, approval ratings for governments’ handling of the pandemic have fallen worldwide in recent weeks.

Even though some countries and regions have flattened the coronavirus curve, and even though concern over the pandemic may have eased slightly in recent weeks, global leaders are generally not getting more credit for their handling of the outbreak.

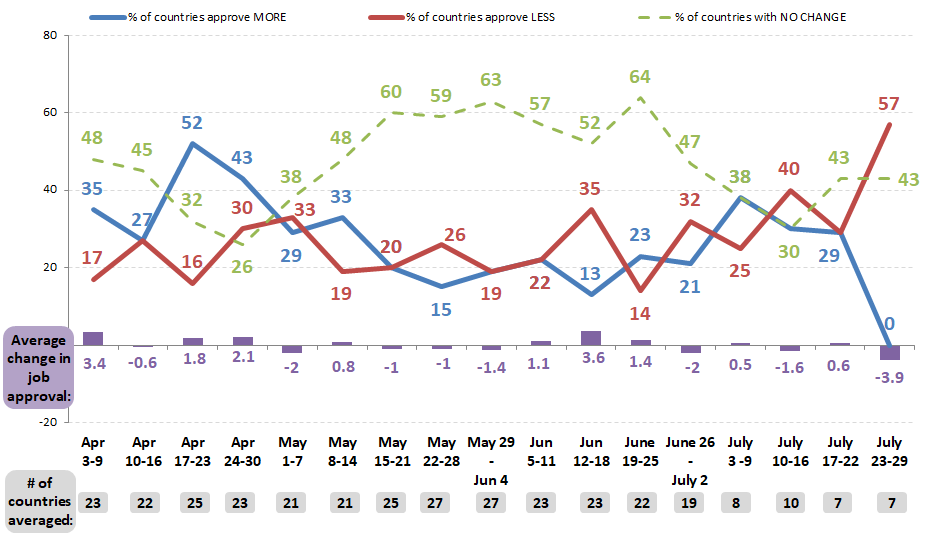

Indeed, an analysis of all government approval ratings on the coronavirus, worldwide, shows a drop in approval ratings in recent weeks. Globally, the average level of government approval dropped in each of the last three weeks, with a 3.9% drop this past week – the largest we have seen since the start of the pandemic (although this week’s figures are based on only 7 countries, and may even out as data on more countries becomes available). As Figure 3 shows, there have been more countries over the past three weeks reporting major (over 3 point) drops in government approval ratings than countries with gains in approval ratings.

All this suggests it may be harder for governments to look good on their handling of the coronavirus the longer the pandemic wears on – even against the backdrops of some progress against the disease.

Figure 3: % of countries with increased or decreased approval of government on COVID-19[2]

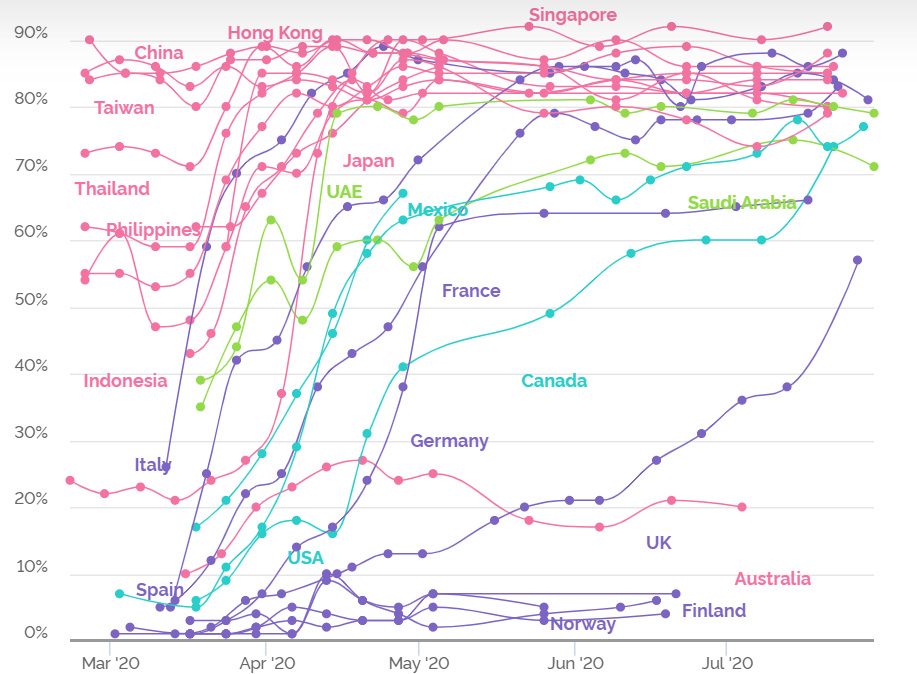

One of the most dramatic changes in global opinion regarding the pandemic has been with regard to wearing face masks. In March, few countries outside Asia had majorities wearing masks; but now, few outside Scandinavia lack a majority who report wearing masks. Majorities across many countries endorse the idea of making it mandatory to wear masks. In the US, while there is strong support for mask-wearing overall, the Trump administration’s equivocal stance on mask-wearing has fostered notably partisan patterns of support for mandating mask-wearing.

One of the biggest pandemic-related shifts in global public opinion and behavior has been with regard to wearing of face masks. As Figure 4 reveals, YouGov’s global tracking surveys show a dramatic shift toward mask-wearing across a wide range of countries, especially outside Asia. By late March, every Asian-Pacific country tracked by YouGov, except Australia and Singapore, already had a majority reporting they were wearing face masks in public places – at a time when the only non-Asian country with a mask-wearing majority was Italy.

Since then, majorities in every non-Asian country in tracking research have started reporting they are wearing masks – except for the Scandinavian countries, which all report less than 10% of their public wearing masks.

Figure 4: % in each country who say they wear face masks when in public places (YouGov)

Across a wide array of countries, there is now majority support for wearing face masks – and even for making it mandatory:

- Australia. Even though the incidence of wearing masks is relatively low in Australia, a July 26 Essential Research survey finds 68% of Australians favor making it mandatory to wear masks in public places.

- Austria. A July 22 Research Affairs poll finds 75% of Austrians agree with requiring mask-wearing. This is true across most of the major parties, though to different degrees: 91% of Green voters, 85% of SPÖ voters, and 76% of ÖVP voters agree with such a mandate. Only voters for the far-right FPÖ are not in favor, with 59% against.

- Canada. A July 13 Angus Reid Institute poll finds 74% support for mandatory mask policies in public places, with some differences in intensity by partisanship. Just over half—55%—of Conservative voters would support such a policy, compared to 91% of Liberal voters or 88% of NDP voters. Nearly three quarters of Bloc Québécois voters support the policy, which was recently made reality in Quebec.

- Italy. A June 23 Istituto Ixe survey finds 57% believe it is still necessary to maintain measures of prevention such as masks and social distancing.

- UK. A July 19 Savanta ComRes poll finds that majorities in Britain believe that face masks should definitely or probably be mandatory across a range of activities, including riding on public transport (83%), shopping at supermarkets or retail shops (77%), or going to pubs or restaurants (65%). A July 17 Opinium poll finds that 71% support mandatory face masks while shopping, and fines of up to £100 for non-compliance. There is little difference in the UK by partisanship: 78% of Labour voters and 77% of Liberal Democrats support the policy, and so do 73% of Conservatives.

- US. In the US, there is strong support for mask-wearing, on average, with 72% of Americans in a July 19 Morning Consult poll saying they support a face mask mandate in public spaces. But there are large partisan differences on this in the US, with 86% of Democrats supporting such a mandate, compared to only 58% of Republicans.

The Trump administration’s resistance to scientific guidance takes place against the backdrop of a rise in faith in science among Americans, relative to six years ago; this may partly explain the fall in approval levels for Trump’s handling of the pandemic.

Each country’s attitudes toward coronavirus partly reflect that public’s views about science. A newly released global poll suggests that the Trump administration’s skepticism toward scientific guidance may have come just as the American public’s faith in science was on the rise.

The World Values Survey (WVS) is one of the largest and most respected periodic global opinion projects. Since 1981 it has carried out 7 waves of global research on a wide array of topics regarding values, politics, and beliefs. This release from the 7th wave was completed in early 2020, with results posted just this month, on July 20. Even though its interviews were completed before the coronavirus was noticed by most of the world, some of the WVS findings concerning science shed light on subsequent global reactions to the outbreak.

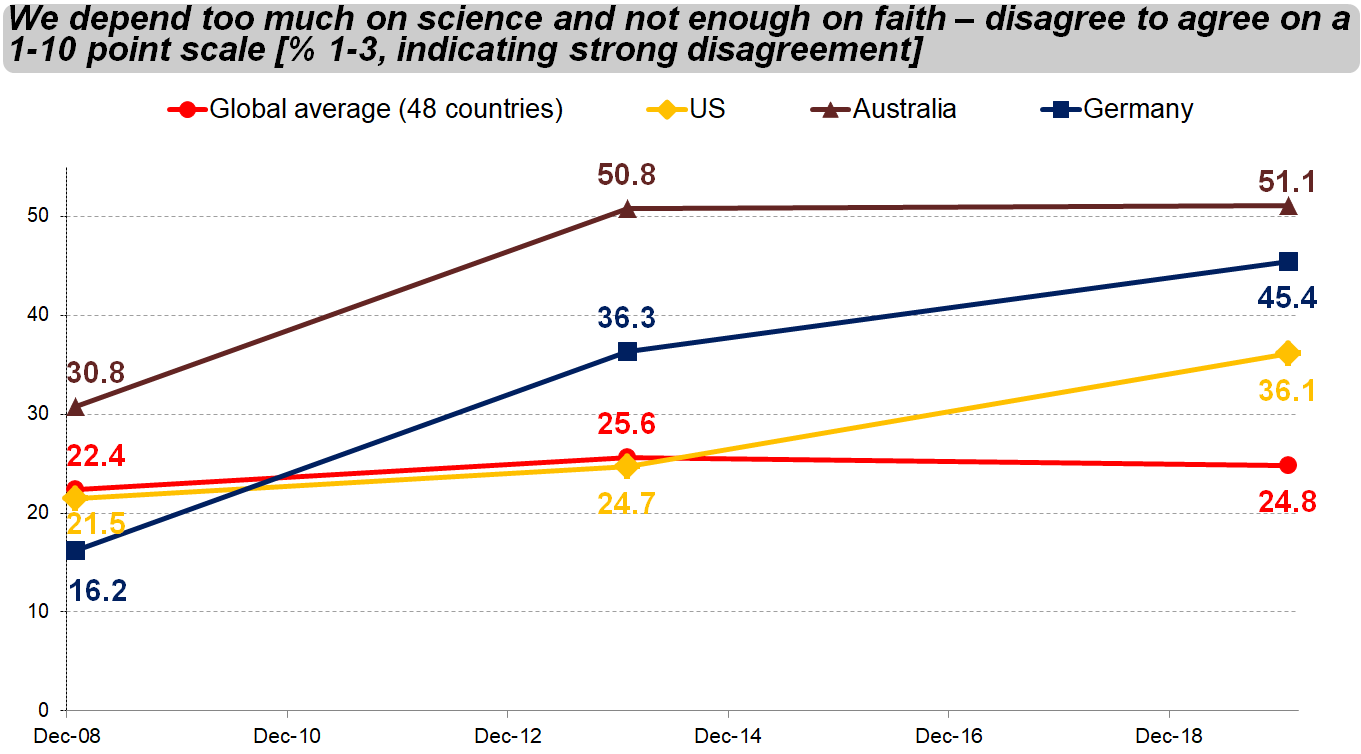

In particular, the new WVS data shows that while the world’s faith in science remained relatively constant, there was a sizeable jump in belief in science in the US between 2014, when the 6th wave was released, and early 2020. As Figure 5 shows, there was general steadiness in the global share (across 48 countries) who strongly disagree with the statement: “we depend too much on science and not enough on faith.” The worldwide share who strongly disagreed (giving a score of 1-3 on a 1-10 scale, with 1 meaning totally disagree and 10 meaning totally agree) only moved marginally, from 25.6% in 2014 to 24.8% in 2020. But in the US, there was a positive jump, from 24.7% to 36.1%.[3]

Figure 5: % in each country that disagree “we depend too much on science” (World Values Survey)

The US still lags behind many other developed countries, like Germany or Australia, in the degree to which the public sides with science over faith. But the large jump between 2014 to 2020 may mean that the US public was starting to have more confidence in science just at the moment the Trump administration began to denigrate scientific findings and expertise. That, in turn, could help to explain why Trump and his administration have received relatively low marks on their handling of the pandemic. Indeed, many polls (including ones this series has earlier reviewed) have found that one of the main things that troubles the US public about the administration’s handling of the crisis has been its denigration of scientific advice.

**Two notes to our readers: We want to flag two final points. First, we have noted that the second half of 2020 has a large number of global elections, and that we will be monitoring these to analyze the impact of the coronavirus. We do not analyze any in this edition because no significant elections occurred in the past two weeks, but we will have many to analyze in upcoming editions. Second, Pandemic PollWatch will be taking a summer break for a few weeks, with our next edition to be published September 17.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 15 installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through July 16, reviewed a total of 1,492 polls from 108 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 87 polls, covering 47 geographies. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] For Figure 3, data compiled by GQR; data only compiled for countries having week-on-week public polling on the question shown. Countries only counted as showing an “increase/decrease” if the week’s change is at least 3 percentage points. Average for change in level of concern is not population-weighted across countries. Question wordings may differ somewhat across countries and weeks. The data from previous weeks has been revised slightly from previous editions of PollWatch to reflect late-arriving data.

[3] Another question from WVS shows the same trend. In that question, respondents rank agreement on a scale from 1 to 10 with the statement: “It is not important for me to know about science in my daily life.” On that question, the share worldwide who disagreed strongly (a score of 1-3) rose slightly from 38.2% in 2014 to 40.0% in early 2020. But in the US, the share rose from 39.1% in 2014 to 48.9% in 2020.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The 15 earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.