The coronavirus triggered a global health crisis and economic crisis; but there is now clear evidence it also triggered a global democracy crisis. A new, first-of-its-kind survey and study, conducted by the non-partisan NGO Freedom House in partnership with GQR, finds that the pandemic has created an opportunity for many leaders and governments to reduce transparency, increase surveillance, arrest dissidents, repress marginalized populations, embezzle public resources, restrict media, and undermine fair elections.

This is the eighteenth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- The coronavirus has triggered a global crisis for democracy and human rights; there is a strong consensus among global democracy and human rights experts that the pandemic is reducing freedom worldwide – including restrictions on speech, media, elections, transparency, minority rights, and more – and is likely to continue to do so for many years.

- Global leaders continue to show wide variation in changes in their approval ratings since the start of the pandemic; President Trump is one of the few leaders who has seen no gain in approval ratings.

- Regional elections in Italy on September 20-21 provide a new example of the impact of the pandemic on electoral results, with at least two of the regional winners benefiting in part from sound management of the coronavirus.

Major Insights

The coronavirus has triggered a global crisis for democracy and human rights; there is a strong consensus among global democracy and human rights experts that the pandemic is reducing freedom worldwide – including restrictions on speech, media, elections, transparency, minority rights, and more – and is likely to continue to do so for many years.

The pandemic’s sweeping damage to global health and economics is by now widely chronicled; but a new study released today shows that the pandemic has also triggered a global crisis for democracy and human rights. The study reveals how leaders and governments worldwide have seized upon the pandemic as an opportunity to restrict freedoms of speech, assembly, media, conscience, and self-governance; to reduce transparency; to expand corrupt practices; and to step up attacks on opposition leaders, journalists, minority groups, and NGOs.

This picture emerges from a first-of-its-kind study by the non-partisan NGO Freedom House in partnership with GQR. The study is based on an online survey GQR conducted of 398 experts and activists worldwide, who collectively focus on democracy and human rights in 105 countries (the report also draws on data and insights Freedom House has covering another 87 countries). The survey provides chilling data on the extent of the new democracy crisis, as well as compelling testimony from these experts, captured in over 130,000 words of open-ended responses (provided in six different languages).

The full Freedom House study includes a full description of the methodology and the full toplines from the survey. An op-ed on the study’s findings, by Freedom House President Michael Abramowitz and GQR Managing Partner Jeremy Rosner, published today in Real Clear Politics, is here.

The main findings of the global survey include:

- The coronavirus triggered a global democracy crisis. By a strong 75-17% margin, survey respondents say “overall, the coronavirus outbreak has been a setback for democracy and human rights in my main country of focus.” Freedom House’s much-cited annual Freedom in the World report has shown democracy and freedom losing ground globally over the past 14 years, but this new survey shows the pandemic is exacerbating the world’s “democracy recession.”

- The impact of the pandemic on democracy and human rights is likely to last for years. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents, 64%, say they expect this negative impact to persist over the next 3-5 years, suggesting the setback for democracy may well outlast the health crisis itself.

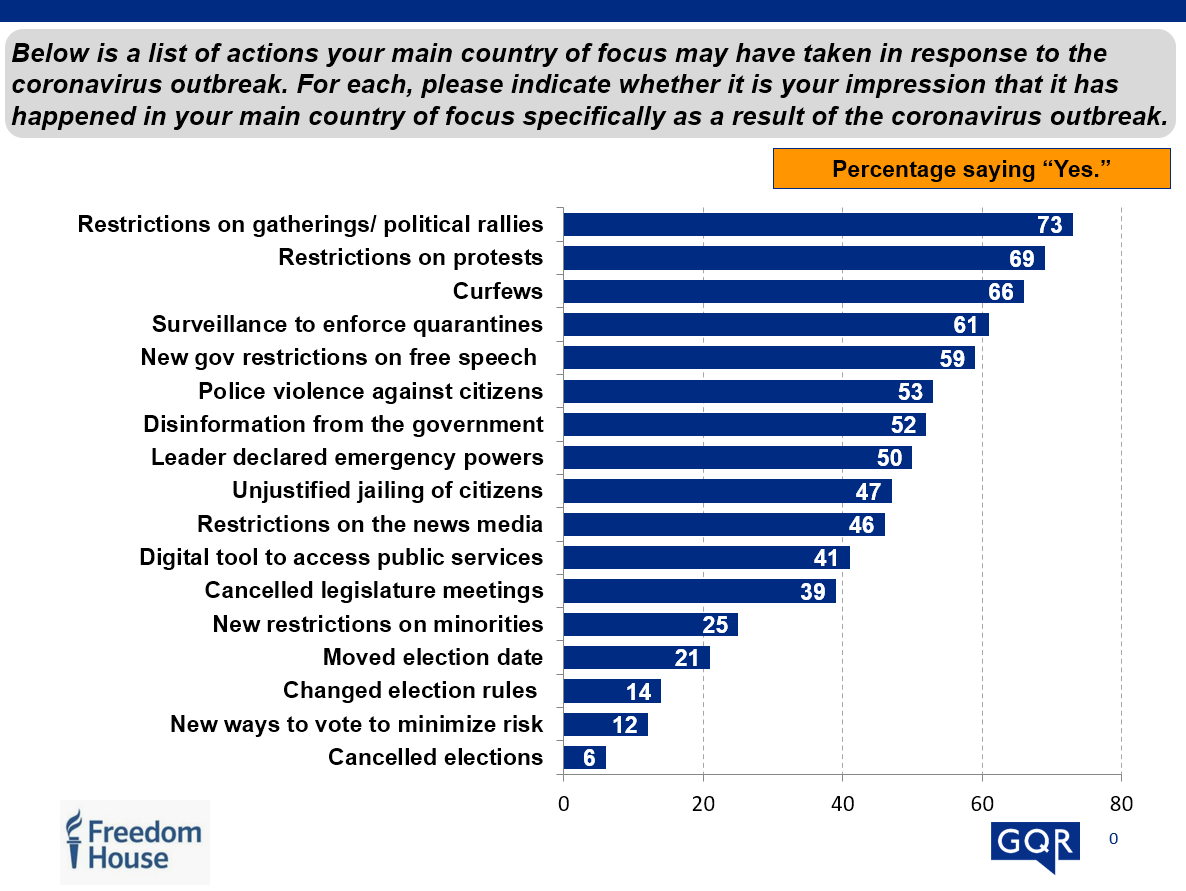

- Leaders are exploiting the pandemic to restrict political activity and speech. As Figure 1 shows, the political restrictions respondents cite most as a result of the pandemic involve restrictions on gatherings and political rallies (cited by 73% of respondents) and restrictions on protests (69%). Another 59% cite new government restrictions on speech. As a Thailand observer says in responding to the survey: “The Emergency Rule Law was introduced so there is a ban on all public gatherings, and it has been used as an excuse for arrests and intimidation of student protestors in many provinces demanding democracy and a new constitution.”

Figure 1: Main political restrictions caused by pandemic

- Governments use the pandemic to restrict the media. As Figure 1 also shows, 46% of the experts surveyed say the coronavirus has led to new or increased restrictions on the news media in their country of focus. As a Bulgaria-watcher writes: “Media freedom has been significantly infringed upon as part of an attempt to impose excessive regulations against disinformation (which in actuality was aimed at silencing opinions that went against the government line) and increasing restrictions on access to information (the amount of time for responding to freedom of information requests has been doubled, for instance).”

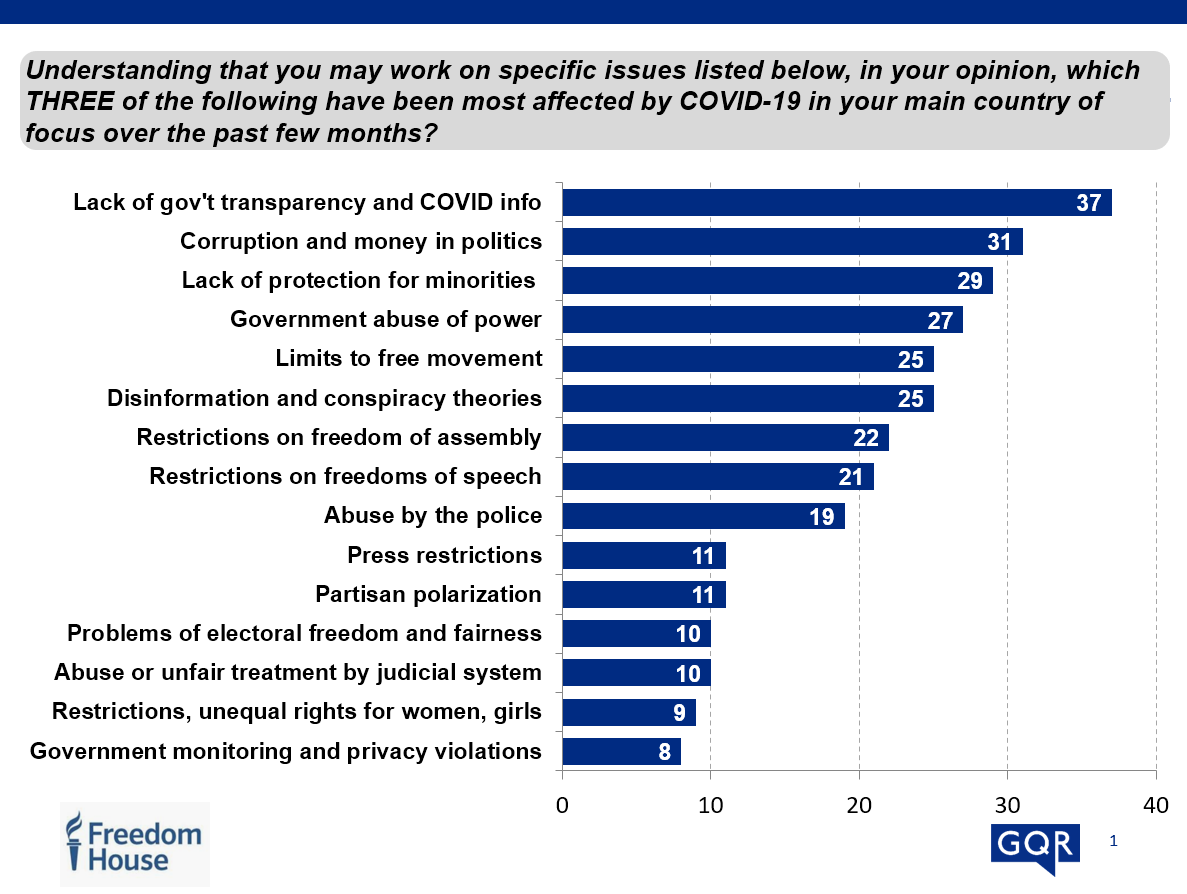

- The pandemic leads to less transparency and more corruption. As Figure 2 shows, the pandemic’s two biggest impacts on democracy and human rights, according to these experts, are on “lack of transparency” (picked by 37% as one of the three main impacts) and “corruption and money in politics” (picked by 31%). Respondents recite at length the ways in which government responses to the pandemic have opened the spigots for corruption. As one respondent recounts, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a raspberry farm infamously won a state contract to acquire ventilators, “companies not registered for medical services were registered overnight to participate in embezzlement of huge funds for purchase of medical equipment of suspicious origin.”

Figure 2: Main impacts on democracy and human rights from the pandemic

- Some leaders are using the pandemic as a pretext for canceling or manipulating elections. Since the start of the pandemic, national elections have been canceled or rescheduled in at least 9 countries, with many more cases at the level of sub-national elections. The pandemic creates real challenges for safely conducting elections, but the changes in many countries are little more than a pretext for limiting democratic rights. As one respondent notes of Belarus, where post-election protests are now posing a serious challenge to authoritarian ruler Alyaksandr Lukashenka, “The authorities, having done nothing to stop the spread of the coronavirus, used the epidemic solely to limit the rights of citizens during the election campaign.”

- Increased repression of minorities and other vulnerable populations. Nearly a third of the respondents (29%) say a lack of protection for minorities and vulnerable populations is one of three issues most affected by the coronavirus. In the face of political pressures, many leaders are scapegoating ethnic and religious minorities; and in light of resource scarcities, some leaders are cutting back most severely on programs on which such communities rely. A respondent writes about Sri Lanka: “Muslims were treated as super-spreaders with some members of government blaming Muslims for people not being able to celebrate the Sinhala and Tamil New Year.”

- A few bright spots regarding journalism and accountability. While the survey paints a mostly grim picture, it does include some bright spots for efforts to support democracy and human rights. The survey underscores the courage and determination of human rights advocates in many places. For example, even though 69% of these experts say new restrictions have been placed on protests, 56% say a significant protest has still taken place in their country of focus since coronavirus restrictions were implemented. Many of the respondents also note how journalists and media outlets are using innovative methods to push back on repression. As one writes of the Philippines: “Journalists covering the pandemic are pushing back through their enterprising methods of reporting despite the limitation in movement. They are also more indignant whenever restrictions are applied to the press, such in the case of the ABS-CBN [the largest media network] shutdown, wherein hundreds of journalists stood in support of the news network.”

Most of the opinion data covered by Pandemic PollWatch over the past seven months has measured the views of the full public in each country. The data from the new Freedom House/GQR study is different in that it measures the opinions of a specific set of experts. But given that these experts are full-time observers of democratic and human rights practices around the world, the new data provide an important window into the global political impacts of the coronavirus pandemic.

Global leaders continue to show wide variation in changes in their approval ratings since the start of the pandemic; President Trump is one of the few leaders who has seen no gain in approval ratings.

As we have noted in previous editions, the coronavirus pandemic has had major implications for the approval ratings and political support of global leaders. Those who have shown “stringency” (speed and firmness) and competence in dealing with the pandemic have tended to see their political support rise; those who have shown less competent responses have often failed to see an improvement, or have seen their political support fall.

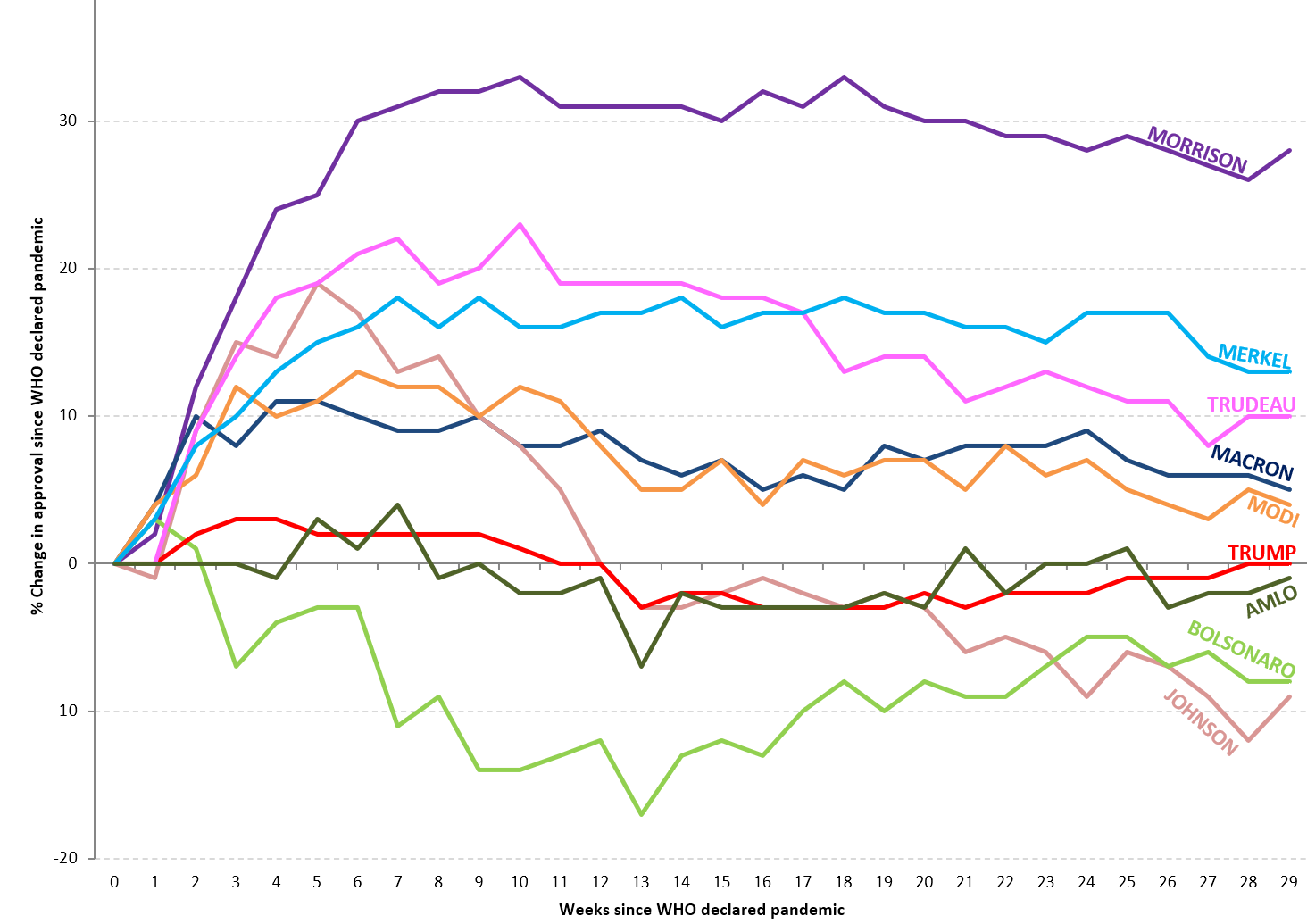

As Figure 3 shows, Morning Consult data tracking the approval ratings of some of the top global leaders (up through September 29) continues to show this pattern. Leaders who have had a strong, science-based response – including Australian PM Scott Morrison, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and Canadian PM Justin Trudeau – have seen a rise in their job approval ratings. But those who have failed to show competence in their responses – including President Donald Trump, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, and British PM Boris Johnson, have seen no rise or even a decline in their approval ratings.

Figure 3: changes in approval ratings of major world leader since start of the pandemic (Morning Consult data, as of September 29; graphic layout suggested by the Economist)

Regional elections in Italy on September 20-21 provide a new example of the impact of the pandemic on electoral results, with at least two of the regional winners benefiting in part from sound management of the coronavirus.

Regional elections in Italy on September 20-21 provide a new example of the impact of the pandemic on electoral results, with at least two of the regional winners benefiting in part from sound management of the coronavirus.

As we have noted in previous editions, the most politically important measurement of public opinion regarding the pandemic comes not from polls but from election results. For that reason, this series of papers has monitored all significant elections since the pandemic started to analyze the impact of the outbreak. While there were relatively few major elections during the early months of the pandemic, there is now a crowded voting calendar, including the upcoming US general election on November 3.

The most recent elections were in Italy, which held regional elections on September 20-21, covering 7 of the country’s 20 regions. Only two small regions switched party control: Marche, which swung from center-left Partito Democratico to the right-wing Brothers of Italy, and Valle d’Aosta, where right-wing Lega came in first place. Apulia, Campania and Tuscany (the biggest prize) were retained by PD. Historically left-wing Tuscany was the region most hotly contested by Matteo Salvini’s Lega. Had his candidate, Susanna Ceccardi, beaten the PD’s Eugenio Giani here, it could have provided Salvini with an important platform from which to attack the ruling national PD-M5S coalition.

Competence in dealing with COVID-19 was a factor in these results. Lega’s popular Veneto president, Luca Zaia, who won 77% of the regional vote, is credited with introducing a successful regional testing regime very early on in the pandemic. Winning in Campania with 69% of the presidential vote, PD’s Vincenzo de Luca has also been strict on COVID-19. Turnout in these elections was around 55% of eligible citizens – which does not represent a major drop from before the pandemic.

Italians also voted in a long-awaited national referendum on the same day, sponsored by M5S and PD but supported by all major parties, on reducing the number of sitting members of parliament. This passed decisively, with almost 70% of the vote. There was not much evidence that the pandemic played a role on the outcome, which mostly reflected frustrations with the political class. Although Five Star Movement did poorly in the regional elections, they can at least claim some credit for this result, as the policy voted in the referendum was one of their 2018 campaign promises.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 17 installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through September 17, reviewed a total of 1,746 polls from 110 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 65 polls, covering 30 geographies. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Guinea-Conakry

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe