As the coronavirus pandemic moves past its sixth month, and as the world moves toward crucial national elections in the US and other countries, how much is the coronavirus still shaping global politics? There are signs that voter concern over the virus has ebbed somewhat globally, with rising attention to economic conditions. Recent elections offer mixed signals about how much government performance on combatting the disease matters to voters, but with some evidence that positive government performance is contributing to governing party victories.

This is the seventeenth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- The coronavirus remains the world’s top concern as the world moves past the sixth month of the pandemic, and there may be some resurgence of concern in some countries in recent weeks; but its dominance has ebbed, with a growing focus on economic conditions.

- Elections held during the pandemic have seen governing parties win in most cases, but in most of these, the governing parties had built positive records on the coronavirus, or it was not a significant electoral issue. The two elections held since our last edition – in Montenegro and Jamaica – tell differing stories about the political impact of the pandemic: in Montenegro, dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic helped fuel an opposition victory; in Jamaica, the ruling party held on to power as a positive economic record outweighed concerns about mishandling of the coronavirus.

- While a strong majority globally says they are likely to take a vaccine once it is developed, a significant minority plans to refuse it, including in the US, where there are strong, bipartisan concerns that the vaccine approval process is no longer trustworthy due to political influence.

Major Insights

The coronavirus remains the world’s top concern, and there may be some resurgence of concern in some countries in recent weeks; but its dominance has ebbed, with a growing focus on economic conditions.

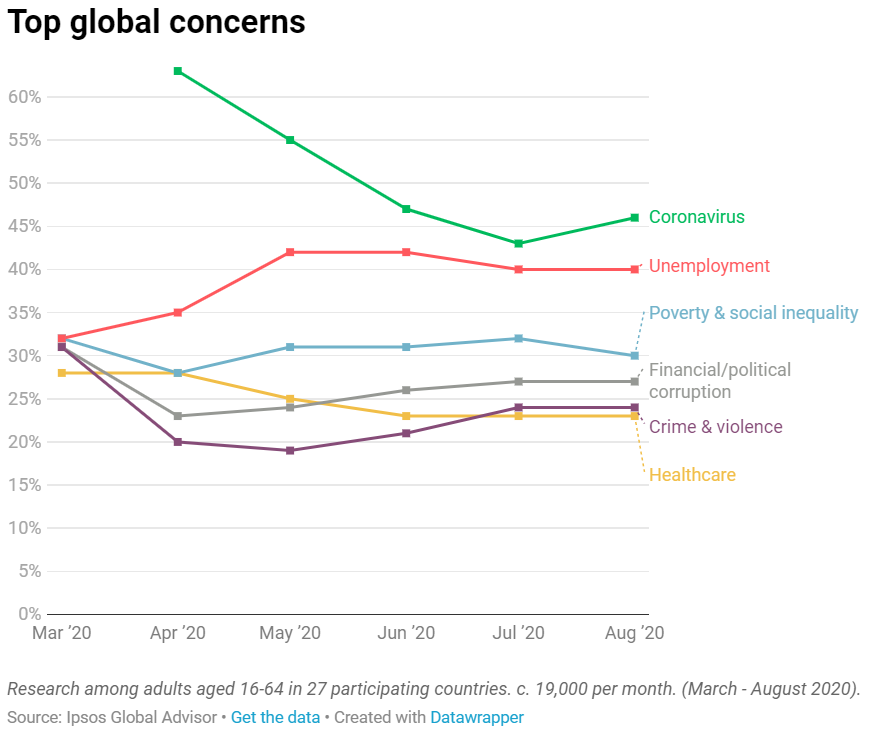

As the coronavirus pandemic moves past its sixth month, it is no longer as dominant a global concern as it was in its early months. As Figure 1 shows, Ipsos tracking across 27 countries finds that, over the summer, the share who listed the coronavirus or health care as one of their top national concerns fell behind the share who cited economic issues – “unemployment” or “poverty and social inequality.” The Ipsos tracking shows some uptick, however, in concern about the pandemic during August, led by double-digit increases over July in Japan, Australia, Belgium, Israel, Poland and the Netherlands.

Figure 1: Top national concerns (Ipsos)

As the Ipsos results suggest, the pandemic and health continue to dominate public concerns in many key countries. Several polls suggest they continue to dominate US concerns as well. But that is no longer the case in many other places. A September 13 Mitofsky survey in Mexico shows that concern over the coronavirus has dropped by over half since May and now is a lower concern than either the economy or crime. In Argentina, an August 17 M&F Public Opinion poll shows that corruption, crime, and economic issues are all more pressing than the pandemic and health. As we note below, an NDI poll in Montenegro found COVID-19 to be only the fourth most important national issue, well behind economic issues. GQR’s proprietary polling in multiple other countries also shows economic concerns now eclipsing public worry over the pandemic.

Elections held during the pandemic have seen governing parties win in most cases, but in most of these, the governing parties had built positive records on the coronavirus, or it was not a significant electoral issue. The two elections held since our last edition – in Montenegro and Jamaica – tell differing stories about the political impact of the pandemic: in Montenegro, dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of the pandemic helped fuel an opposition victory; in Jamaica, the ruling party held on to power as a positive economic record outweighed concerns about mishandling of the coronavirus.

The most important test of how the pandemic is affecting politics comes not from polls, but from election results. Since the WHO declared the coronavirus pandemic in mid-March, there have been 11 credible and contested national elections worldwide.[2] In 8, the governing party won; in the other 3, the opposition took power. In 7 of the 8 cases where the governing party won, the government benefited from relatively good handling of the pandemic, at least up to the time of the election, or from COVID-19 not being a major election issue. Of the 3 opposition victories, poor government handling of the pandemic contributed to the outcome in one case, and in the other two cases COVID-19 was not a major electoral focus.

In this issue, we examine the impact of the pandemic on the two elections that occurred since our last issue: Montenegro and Jamaica.

In Montenegro’s national elections on August 30th, the ruling DPS lost the parliamentary majority it had held for three decades. Although DPS won more seats (30) than any other party, the opposition parties have agreed to form a government, holding a bare majority of 41 seats between them in the 81-seat legislature.

The coronavirus contributed to DPS’s defeat. On May 25, after a strict lockdown, DPS Prime Minister Duško Marković declared Montenegro to be “the first coronavirus-free country in Europe,” and lifted preventative measures. But only weeks later, the number of cases started to rise again.

The pandemic did not discourage Montenegrins from voting, however: the 77% turnout was slightly higher than in previous years. In an August poll by NDI, 79% of Montenegrins said that “there is nothing COVID-19 related that will prevent me from voting.”

There were many electoral issues at play other than the coronavirus. As noted, the NDI poll showed COVID-19 was only the fourth most important issue to voters, well behind economic issues. A controversial new law on religion also became a flash point for the campaign, angering the highly influential Serbian Orthodox Church. But this was a case where mishandling of the coronavirus added fuel to an opposition victory.

In Jamaica, the ruling Jamaica Labor Party (JLP) secured a landslide victory in the September 3 general election – despite poor handling of the pandemic. The opposition People’s National Party (PNP) won just 15 seats compared to 49 for the JLP, the latter’s largest margin since the 1980s.

The government of Prime Minister Andrew Holness faced criticism for its coronavirus response. By Election Day, the number of new cases had increased by nearly 10 times since the beginning of August. Yet the JLP’s pre-pandemic positive economic record – including declining unemployment, poverty reduction, and infrastructure investments – appear to have overshadowed public frustrations regarding the growing coronavirus case numbers.

The coronavirus did, however, appear to deter many Jamaicans from voting. The 37% level of turnout was down from 48% in the previous (2016) election, producing the lowest national voter turnout since the uncontested 1983 general elections. PM Holness acknowledged fear of the virus in his victory speech. All voters were required to wear a mask, have their temperatures checked, and wash their hands before casting a ballot. Those currently in isolation after testing positive for COVID-19 were allowed out to cast ballots after the polls officially closed to the wider public.

While a strong majority globally says they are likely to take a vaccine once it is developed, a significant minority plans to refuse it, including in the US, where there are strong, bipartisan concerns that the vaccine approval process is no longer trustworthy due to political influence.

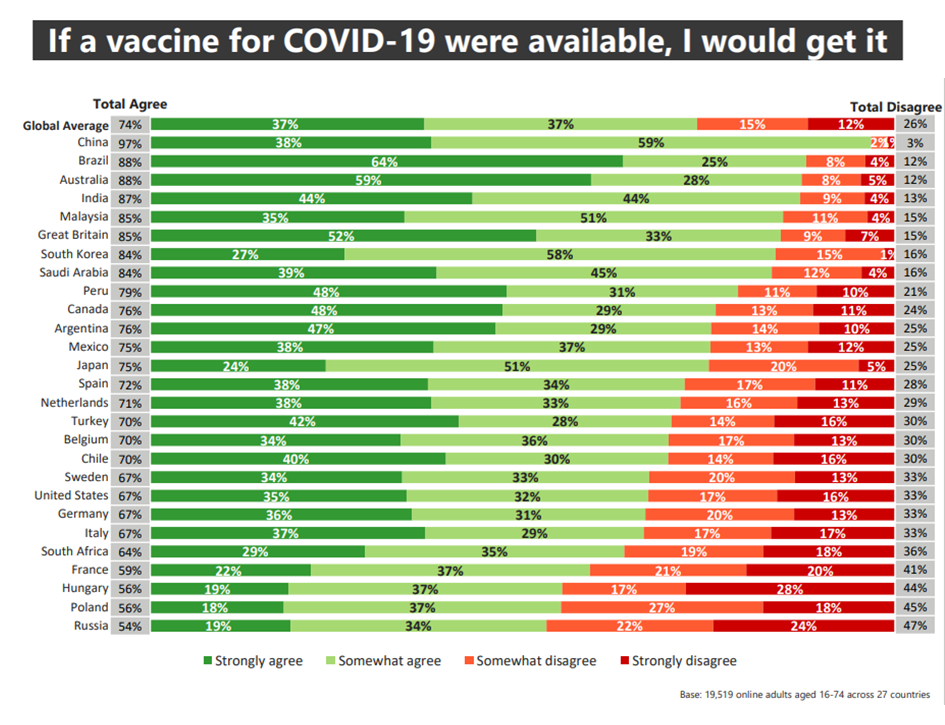

Global attention is steadily turning to questions surrounding a vaccine for the coronavirus – when an effective vaccine will become available, how it will be distributed, and whether it will be safe to use. As Figure 2 shows, the Ipsos August tracking survey of 27 countries shows that 26% of respondents across these countries say they would not get the vaccine once it becomes available. Resistance to getting the vaccine is highest in Russia, at 47%, but it is also higher than the global average in the US, at 33%.

Figure 2: Likelihood of getting the vaccine once it is available (Ipsos)

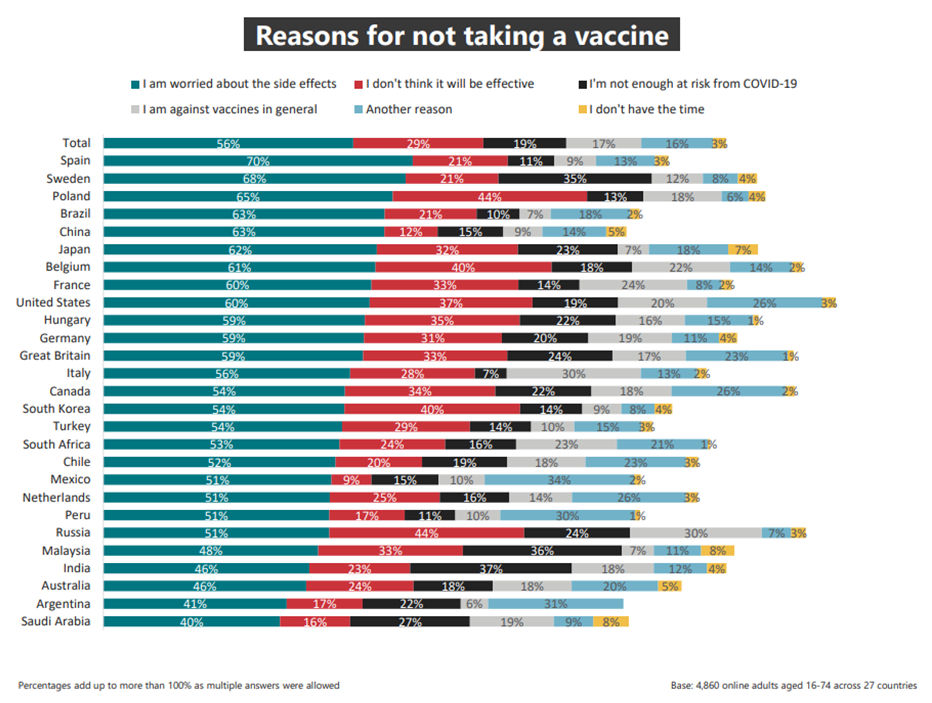

As Figure 3 shows, the Ipsos research suggests the main reason for people not planning to get the vaccine is concern about side effects, cited by a 56% majority worldwide among those who do not plan to get vaccinated. In the US, there is also higher-than-average concern that the vaccine will not be effective, cited by 37% of Americans who do not plan to get vaccinated, compared to 29% across the 27 countries surveyed.

Figure 3: Reasons, among those not planning to take a vaccine (Ipsos)

In the US, surveys suggest particular public concern that politics is interfering with the development and approval processes for a vaccine. A September 3 Kaiser Family Foundation survey finds a 62% majority very or somewhat worried the FDA will “rush to approve a coronavirus vaccine without making sure it is safe and effective due to political pressure from the Trump administration.” The KFF survey finds a 54% majority of Americans would choose not to get vaccinated if the vaccine were approved before the November election, presumably due to concerns about such political pressure. A September 4 YouGov poll finds a 50-14% majority of Americans believe the timing of the COVID-19 vaccine development is being shaped more by political than public health interests. Even a 34-24% plurality of Republicans believe this.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 16 installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through July 31, reviewed a total of 1,579 polls from 108 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 167 polls, covering 58 geographies, including two not previously examined. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] South Korea on April 15; Malawi on June 23; Mongolia on June 24; Poland (presidential) on June 28; Croatia and Dominican Republic on July 5; Singapore on July 10; North Macedonia on July 15; Sri Lanka on August 5; Montenegro on August 30; and Jamaica on September 3. Not included here are elections in Mali, Burundi, Serbia, Syria, and Belarus, which were marred by violence or irregularities, boycotted by the opposition, or otherwise undemocratic.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Ethiopia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Guinea-Conakry

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The 16 earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.