an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

This is the eighth in a series of weekly papers from GQR summarizing and analyzing all available data on global opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. The major insights in this paper:

- As a global debate heats up over the civil liberties implications of contact-tracing apps, public opinion worldwide appears mostly split and malleable on the necessity and wisdom of such technologies. Publics appear to easily understand both the benefits and risks, and the outcome of the debate in each country may partly depend on which gets communicated more quickly and effectively.

- Global concern about contracting the virus continues to show a long-term pattern of stabilizing and easing.

- Public approval for the job national governments are doing on COVID-19 has become more stable, after initial “bumps” in approval in many countries; approval levels in the US remain low, relative to most other countries with comparable data, and President Trump’s overall job approval rating has shown less increase since the pandemic declaration than most other world leaders.

Major Insights

Global public opinion appears divided and malleable on the necessity and wisdom of contact-tracing apps that might aid in fighting the pandemic, but at some cost to privacy and civil liberties.

The world is in the early days of a debate about whether to deploy new technologies to track personal information in order to fight COVID-19 and future pandemics. Already, many governments have tapped into their citizens’ cell phone use, credit card data, and security camera footage as part of efforts to combat the spread of the coronavirus. Google and Apple in April announced a joint project to develop a contact-tracing app that might ultimately turn huge shares of the world’s 5.2 billion smartphones into contact-tracing tools. Such initiatives raise major questions about privacy and civil liberties.

This global discussion is reminiscent of the post-9/11 decisions over whether to give governments new anti-terrorism powers, but now the imperatives favoring data tracking are rooted more in matters of economics and public health. Public opinion on how best to balance health security with civil liberties will play a role in that debate, so it is useful to examine global public opinion on these tradeoffs.

Available opinion data from around the world generally suggests that publics are closely divided on the necessity and wisdom of such technology, but also still at an early and persuadable stage of their thinking.

Opinion is closely divided on contact-tracing apps in most countries, despite a general desire for stringent action against COVID-19. Most of the global polling suggests publics are roughly split on the idea of new technologies – and especially cellphone-based apps – that would be used to track personal information as part of combatting COVID-19 and other pandemics. The divided nature of opinion, even at a moment when world-wide concern about contracting the disease is high, suggests serious public reservations about the necessity and wisdom of such steps.

In the abstract, many publics appear open to strong steps that might abridge personal freedoms. Our April 2 edition of Pandemic PollWatch noted evidence of a global desire for “stringency” in government responses to the pandemic. In the face of high fears, there appears to be a pattern of publics worldwide wanting their government to do “more” rather than “less” to fight the coronavirus.

Yet despite this strong, global support in the abstract for taking steps to combat COVID-19, publics are generally split on whether to support phone-based contact-tracing apps:

- US: An April 21 YouGov poll found that a narrow 37-40% margin of Americans disapproves of releasing apps that would be used to track the spread of COVID-19 through cellphone data. Respondents were also split, 35-37%, leaning against personally installing the app. Similarly, an April 26 Washington Post/University of Maryland poll found a 41-41% split on whether people would use such an app. As noted below, some other polls show stronger support in the US, but they tend to be ones that stress specific benefits of the app as part of the question wording.

- Canada: An April 26 Leger poll found Canadians about evenly split – 45% agreeing, 48% disagreeing with the idea of “government using location data from people’s mobile devices to track whether people are respecting social distancing/self-isolation measures.” Americans in the same poll split 44-43%.

- Australia: An April 26 Essential Vision poll found only a 40-32% plurality of Australians would download a Bluetooth-based app that does not track geo-location, with 28% unsure.

- France: An April 9 IFOP survey found the French public split 46-45% on whether they would install a contact-tracing app that does not include geo-location data, with a 53-47% majority opposed to the idea of the health authorities making it compulsory to install such an app.

- Germany: A March 30 YouGov poll found Germans split 44-43% on whether they would install a contact-tracing app on their cellphones.

- Italy: A 38% plurality of Italians in an April 23 TP poll agreed that this kind of app is necessary to track those who are infected, with 32% saying “no, it is too invasive” (and 25% saying “it depends”).

There are some notable exceptions to this pattern. In the UK, Norway, and possibly some other countries, there appears to be majority support for the idea of such an app. But as discussed below, there are special circumstances in each case that explain the higher levels of support.

Support for a contact-tracing app often splits on partisan lines. In the US, attitudes toward a contact-tracing app split along partisan lines, although in a somewhat surprising way. Despite much lower support early on among Democrats for anti-terrorism legislation such as the Patriot Act, Democrats are significantly more supportive at this point of the idea of a contact-tracing app.

In the YouGov US poll noted above, a 50-27% plurality of Democrats approved of contact-tracing apps, while a 31-53% majority of Republicans disapproved (Independent voters leaned against it, 31-43%). Similarly, an April 20 Kaiser Family Foundation poll found consistently higher support among self-identified Democrats and among the young – a demographic that leans heavily Democratic – for contact-tracing apps.

Other polling shows Democrats strongly perceive President Trump to be acting too slowly in his response to COVID-19, which may explain their greater support for the app. (In an April 19 poll sponsored by GQR, 85% of Democrats who believe quick action is important for a leader say that Donald Trump has not acted quickly in handling coronavirus.) Conversely, Pew finds in an April 26 poll that Republicans are more likely to feel that the media has “greatly” or “slightly” exaggerated the threat of COVID-19(68%, compared to 30% of Democrats), which may help to explain their greater resistance to taking the additional step of using such invasive apps.

In the Essential Vision poll in Australia, support for the app also shows partisan differences. A 47% plurality of respondents who support parties in the governing coalition say they would download a contact-tracing app, but only 36% of Labor voters.

Attitudes toward contact-tracing apps appear fluid, and depend on key secondary considerations. Publics in many countries appear to be in an early stage of thinking about the tradeoffs involved in a contact-tracing app. Although this debate is in its early stages, and there are relatively few countries with comparable polling on these matters, polling responses appear to depend heavily on how survey questions address key subsidiary questions, such as:

- What data will be collected?

- Who will collect and manage the data?

- Who has access to the data?

- What are the purported purposes and benefits of collecting the data?

- How effective it is the data collection effort likely to be at meeting those goals?

- What are the risks – especially the chances that their data will be stolen or used improperly?

- Are there country-specific issues that would boost acceptance – for example, has the country already launched such an app?

What data will be collected? Support appears to be lower in polls that talk about collecting and using geo-location data. Many of the potential apps do not collect geo-location data; some, like the Google-Apple concept, rely on Bluetooth technology to collect the contact information for people who come into close proximity with the cellphone owner, but not information on where that proximity took place. For example, despite the generally even split among the US public about using an app for contact-tracing, a March 22 Morning Consult poll finds a 57-35% majority would be “uncomfortable” once the poll adds the proviso that “technology companies [would share] your location data, including where you have traveled, with the government so that the government could better track the spread of the coronavirus.”

Who will collect and manage the data? In the US Kaiser Family Foundation poll cited above, public openness to the app greatly depends on the question of who will manage it. It finds over 60% are willing to download the app if it is managed by “their local health department” (62%), “the state health department” (63%), or the CDC (62%); but only 31%, if it is managed by “a private tech company.” Similarly, in the Washington Post/University of Maryland poll cited above, majorities of respondents with a smartphone trust public health agencies (57% trust them) or universities (56%) to protect the anonymity of their data with such an app, but majorities distrust health insurance companies (52% distrust them) or “tech companies like Apple and Google” (56%).

Who has access to the data? There are indications that more people support tracking contact data if it is only shared with cellphone users themselves, rather than being shared with public authorities. In the KFF poll, a slim 50-47% majority would be willing to download an app that “tracks who you have come in close contact with, and then alerts you if you have come into contact with someone who tested positive for coronavirus so that you can take steps to protect you and your family.” That majority flips to a 45-53% share that are unwilling to download such an app if the app “provides that information to public health officials in order to track the spread of the coronavirus.”

What are the intended purposes and benefits of collecting the data, and how effective will it be? Responses to polling questions about such apps tend to be more favorable if the question indicates the purported benefits of collecting the information. For example, an April 22 JL Partners poll in the UK finds strong 58-20% support for downloading an NHS app, but the question wording starts by stressing that the app is part of a plan to re-open the country: “If it was part of government’s approach to easing the lockdown, how willing would you be to do or support the following: download an NHS app to monitor the spread of the virus by tracking people’s movements?”

In the US, the KFF poll also finds that much larger shares of the public are receptive to the app if they hear information about the goals and benefits of the app. Big majorities would be more willing to download the app if they heard “it would allow many more people to go back to school” (66% more willing); “allow many more businesses to re-open and start up the economy” (66%); or “would give you information so you can talk to your doctor about what to do if you come into close contact with someone who has tested positive for coronavirus” (62%).

An April 8 Realmeter poll in South Korea finds very high support—78%—for a wristband device, only to be worn by people in quarantine, designed to ensure they do not leave their restricted area. Restricting the imposition of this step on people who have tested positive may increase its appeal.

A set of polls in Europe and the US sponsored by the Open Society Foundation underscores the impact that positive information can have on support for this kind of app. In polls completed April 10 in the UK, Germany, France, Italy, and the US OSF uses an innovative survey design that starts by reading respondents an extensive (roughly-200-word) description of how the app would work. One version, for example, says that the app would be developed by the CDC; that it would NOT access contacts, photos, or other cellphone data; and that only the CDC would have access to the data collected. After providing such information, the survey finds very high levels of likelihood to use the app: 86% in Italy; 79% in France; 74% in the UK; 70% in Germany; and 67% in the US. These figures are not reliable measures of the “current” willingness to install the app, but they may provide an estimate of how many people in these countries might be open to using it if they receive the right kind of communication.

How effective is the data collection effort likely to be at meeting its goals? Such positive goals only improve support if they are plausible. Even though respondents may like the idea of such apps helping to stop the spread of the virus, there is evidence that some publics may doubt whether the app will actually do so. According to the Pew poll noted above, a 60-38% majority of Americans say that location-tracking by the government would “not make much of a difference” in limiting the spread of the virus; only 16% say would help a lot.

What are the risks – especially of the data being stolen or improperly used? Just as respondents become more likely to support the idea of an app as they hear about its purported benefits, large shares become less willing to use the app once they hear about its risks. For example, 70% of Americans in the KFF poll say they would be unwilling to download and use the app if they hear that “there is a chance that the data could be hacked.”

Similarly, even though 65% in an April 28 Survation poll in the UK express support for the idea of a contact-tracing app, 78% say it is “very” or “quite important” that such an app “takes account of civil liberties and protects people’s privacy.” Such results suggest global publics find it easy to understand both the appeal and risks of such technologies, and that public support may ultimate depend on which set of factors get communicated more quickly and effectively.

Are there country-specific conditions that would change acceptance? Some countries have particular circumstances that may influence the willingness to embrace steps such as a contact-tracing app. In South Korea, for example, vivid perceptions that the government mishandled the 2015 MERS outbreak likely strengthened the demand for stronger measures against COVID-19. Similarly, there may be stronger support for a contact-tracing app if a country’s government has already launched one (assuming the government is not hugely unpopular). For example, Norway already launched an “Infection Stop” app, and 60% of the population has already downloaded it from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. People who have already downloaded and/or used the app will presumably have a more positive feeling about such technology. Similarly, a March 26 Israeli Voice Index poll finds that a 59% majority in Israel – where collection of cellphone location data began in March – believe the country’s security agency will use the location data it has been given only for the purpose of preventing the spread of the coronavirus.

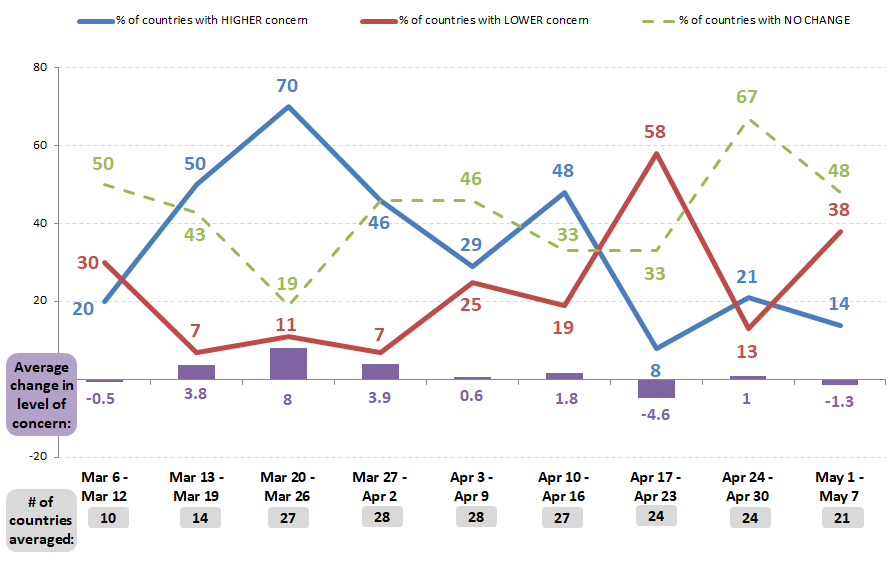

Global concern about contracting the virus continues a stabilizing, downward trend

Global polling data this week shows that levels of concern about contracting the virus have generally dropped, reinforcing the impression of a long-term easing of concern, after intense alarm following declaration of a pandemic in early March. In 86% of the countries reporting such weekly data, the share of the public that is concerned about contracting the virus is either steady (48% with a change of less than 3 points) or down (38% with at least a 3 point drop in concern). Last week, the share with steady or reduced concern was about the same, 80%, but more of those countries this week are showing reduced rather than steady concern. On average, the level of concern dropped by 1.3 percentage points (not population-weighted across countries).

Figure 1: % of countries with higher or lower levels of concern about contracting COVID-19

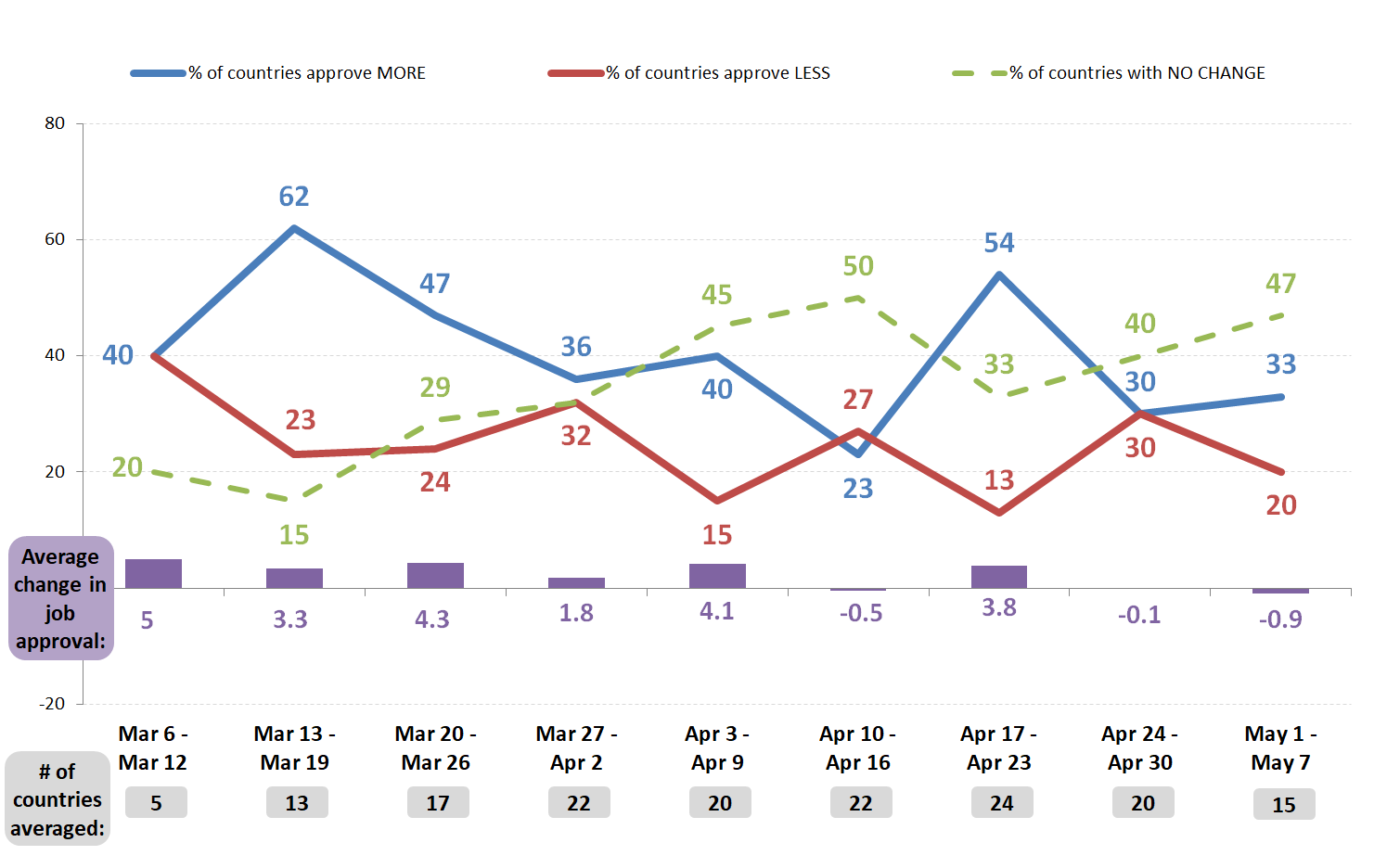

Government job approval ratings on handling COVID-19 also relatively stable, but wide variation in overall job approval levels of major national leaders, with low approval in the US

There also continues to be a relatively stable picture regarding job approval ratings for how governments are dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. As Figure 2 shows, about half of all countries with such data have had no major change (less than 3 percentage points) in their government’s COVID-19 job approval rating compared to the previous week. Of the rest, slightly more (33%) have seen a notable improvement (at least 3 points) in job approval, compared to those with declining job approval (20%). The average level of COVID-19 job approval declines this week by just under 1 percentage point.

Figure 2: % of countries with higher or lower levels of government job approval on handling COVID-19

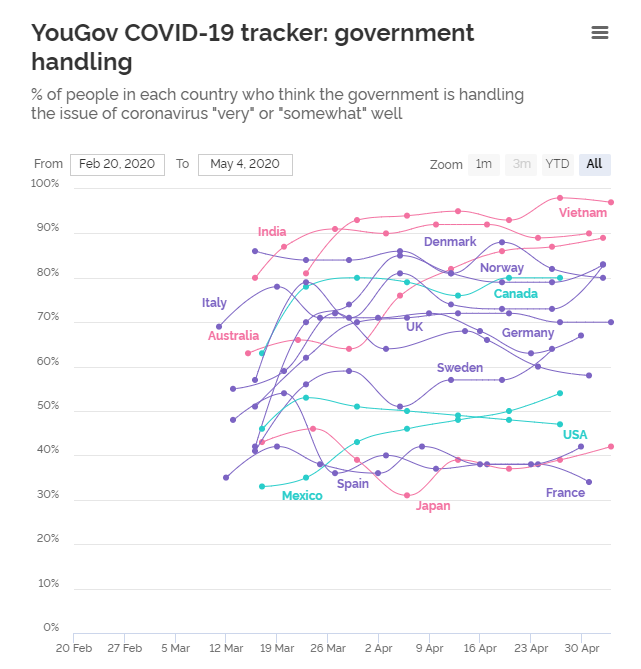

Although there is general week-to-week stability within countries on COVID-19 job approval, it is worth bearing in the mind that absolute levels of COVID-19 job approval differ widely, as do the long-term trends in these numbers, from one country to another. YouGov, which provides most of the world’s weekly COVID-19 job approval data, provides a useful long-term chart of all the countries they are tracking, reprinted as Figure 3.

Figure 3: government COVID-19 job approval for 16 countries (YouGov)

YouGov’s US data is notable for several reasons. Among the 16 countries YouGov tracks, the US ranks 4th lowest on COVID-19 job approval, at 47%; only Spain (42%), Japan (42%), and France (34%) score lower. The US is also one of only 6 countries that saw any drop in its COVID job approval since March 23, and only France saw a bigger drop in COVID-19 job approval over that period – a 20-point drop in France, compared to a 6-point drop in the US (job approval over this period was down 4 points in Denmark, Italy, and Japan, and down 1 point in the UK; the rating was up in all of the others).

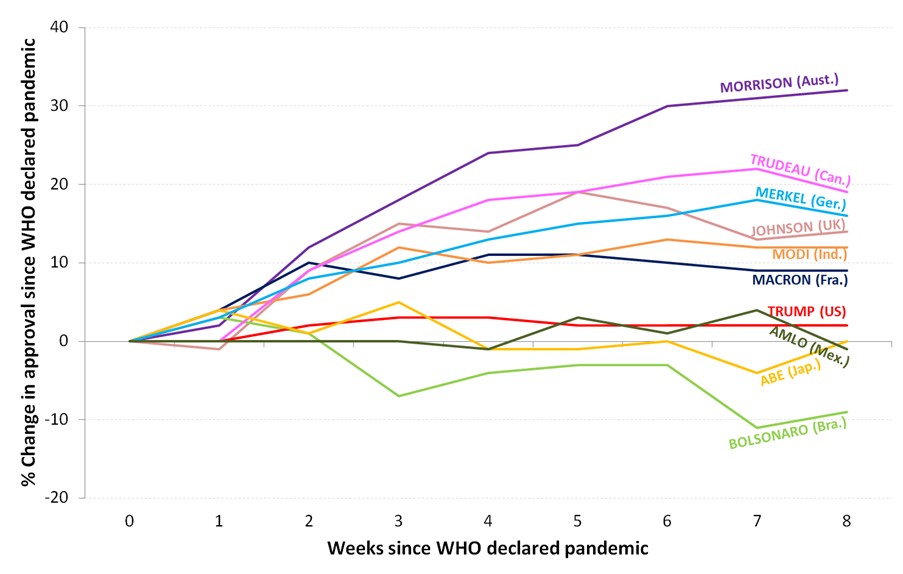

The US also ranks relatively low in terms of how the overall job approval ratings of national leaders have changed since the WHO declared a pandemic on March 11. President Trump’s approval has been notably flat during this period – it is now up only 2 point above its March 11 level – despite the fact that past US presidents have seen sizeable, months-long rises in their approval levels after comparable national disasters. Of the 10 national leaders tracked over this period by Morning Consult polls, 6 have seen their approval levels rise more than Trump. Only 3 have seen less improvement: Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (no change since March 11), Mexico’s President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (known as “AMLO,” down 1 point) and Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, who is down 9 points.

Figure 4: Change in national leaders’ overall job approval rating since pandemic declared (Morning Consult polls, with credit to The Economist for originally displaying the data in this manner)

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., the pandemic’s impact on movie-going) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations.

Our first seven installments of Pandemic PollWatch, on March 20 and 27, and April 2, 9, 16, 23, and 30, reviewed a total of 618 polls from 97 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 95 polls, covering 41 countries, increasing the total number of geographies with reviewed public opinion data up to 98. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, polls reviewed here vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The seven earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.