an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

This is the fifth in a series of weekly papers from GQR summarizing and analyzing available data on global opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. The major insights in this paper:

- Despite some mixed data, global public concern about the virus continues to show signs of leveling off. Across countries with relevant data, the average increase in concern about the virus moves up this week by less than 2 points, compared to a 8-point weekly gain mid-March.

- Global job approval ratings for government handling of COVID-19 continue to trend down, after a mid-March bump. On average, across countries with relevant data, the average job approval rating for handling COVID-19 fell by one point this week.

- New research from GQR finds that, at least in the US, three leadership qualities emerge as the most important in shaping whether the public thinks its leaders are doing a good job handling the pandemic: relying on scientists and other experts, communicating truthfully with the public, and acting fast. Global data suggests that acting fast may be a crucial variable in other countries as well.

- In the first major national election since the coronavirus outbreak was declared a pandemic, President Moon Jae In’s governing Democratic Party scored a landslide victory in national legislative elections yesterday. The outcome, marked by historically high turnout, shows that some leaders may be able to post political gains even against the backdrop of a high toll from COVID-19.

Major Insights

Worldwide concern about contracting the virus continues to level off, though with some mixed signs

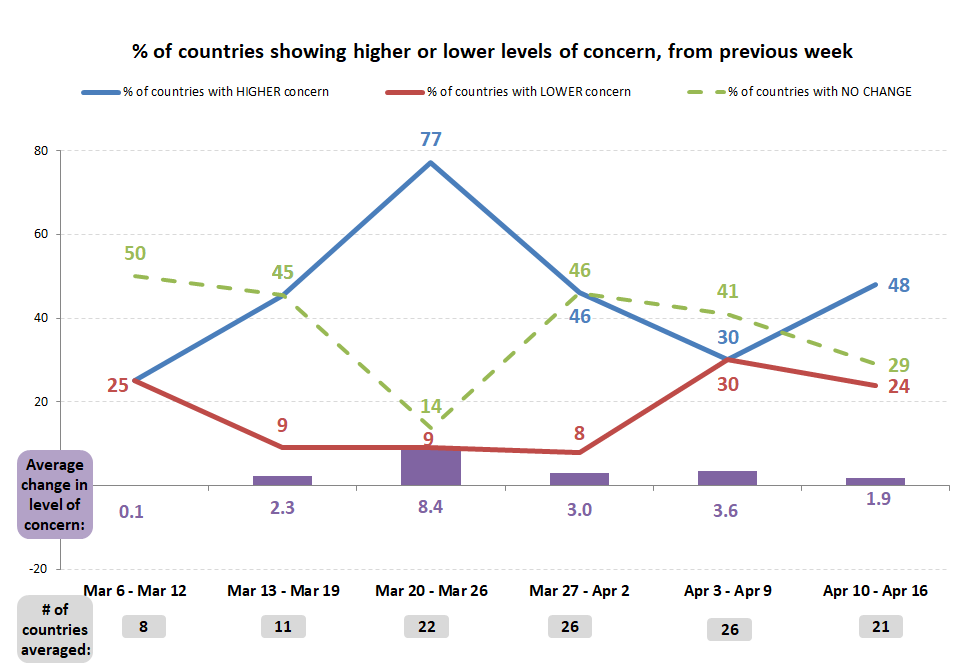

This week’s global data shows that worldwide levels of public fear about contracting the virus continue to level off. As Figure 1 shows, during late March, across all countries with weekly data on this question, the average increase in the share of publics saying they were “very” or “somewhat concerned” about coronavirus moved up by over 8 points in one week. Now the weekly increase is less than 2 points. That is the slowest rate of increase in concern since early March.

There are some mixed signals in the data. In particular, this week there is a rise in the percentage of countries reporting increased concern about contracting COVID-19 – up from 30% of countries last week to 48% this week. This is something to monitor carefully going forward. Yet there is a 53% majority of countries now showing no change (29%) or a decrease in concern (24%). That is a big change from late March, when 77% of all countries with such data were showing an increase in concern.

Figure 1: Global change in levels of “very/somewhat concerned about contracting COVID-19”[2]

Global ratings for job approval on handling COVID-19 continue to trend down, after a mid-March bump

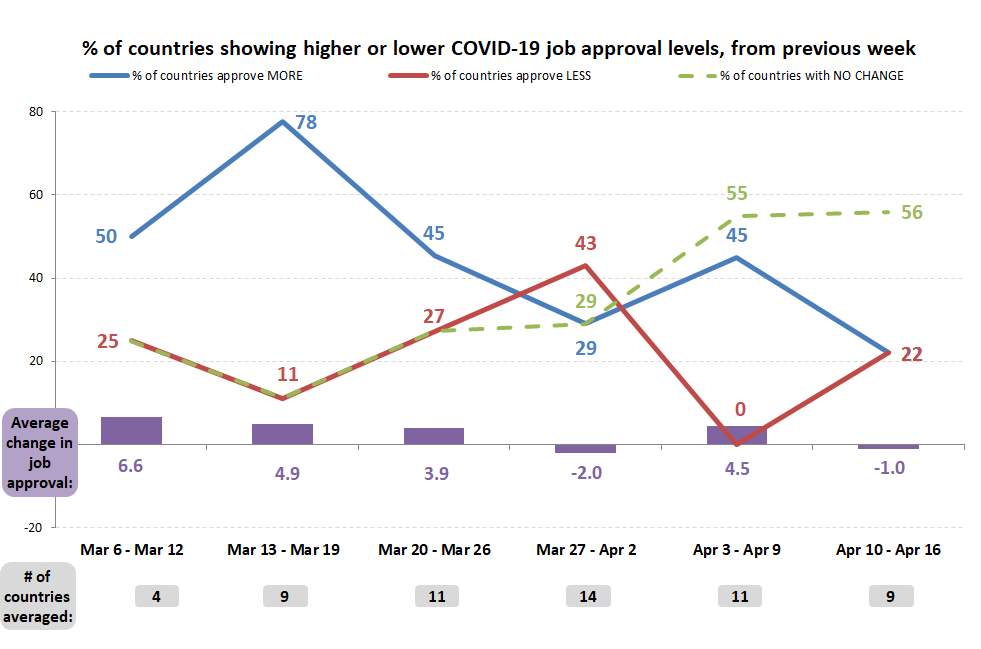

This week’s data also shows a continuation of the long-term decline in global approval of the job national leaders are doing on COVID-19. As noted in previous weeks, mid-March saw a global spike in such approval, as publics appeared to rally around their leaders in the early days of the crisis. At that point, as Figure 2 shows, 78% of the countries with regular opinion data on COVID-19 job approval showed an increase in government approval on handling of the pandemic.

But by early April, more countries were registering drops in approval rather than increases. Now, a majority of countries (56%) show no real change (meaning less than a three-point change) in government job approval on coronavirus; just under a quarter (22%) show an increase in job approval, and the same share show a decrease. Across all countries with data on this question, job approval on COVID-19 dropped this week by an average of 1 point.

Figure 2: Global change in approval of national government’s job on COVID-19

For political purposes, what is even more fundamental than approval levels are election results. The final section in this week’s edition discusses election results from South Korea – the first democratic country to hold a national leadership election since the coronavirus outbreak was declared a pandemic on March 11.

What does positive job approval on COVID-19 mean? In the US, the public is looking for their leaders to trust the experts, communicate truthfully, and act fast.

The preceding section looks at whether publics approve of the job their leaders are doing on handling the COVID-19 pandemic. But what does job approval on COVID-19 mean? What aspects of handling the pandemic are most important to people worldwide? Does it differ across countries?

Global opinion research has not explored these questions much so far. To advance the discussion, GQR sponsored qualitative and quantitative research among US voters: a national online survey of 1,068 registered voters, conducted April 8-12, and a nation-wide online focus groups composed of swing voters conducted April 14.

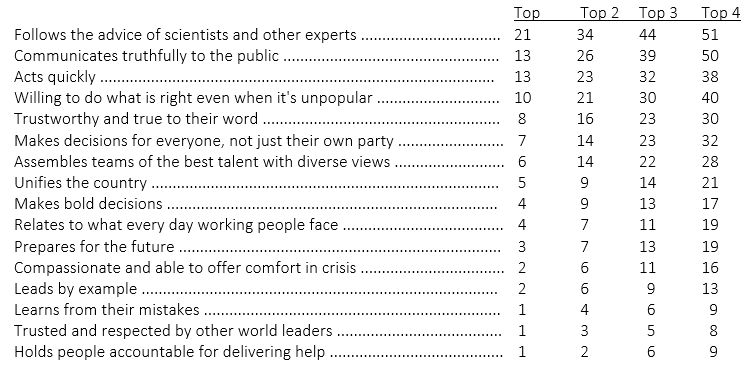

The survey and focus group tested 16 leadership traits that might be important to the US public in evaluating the job their leaders were doing on COVID-19. The research reveals three of these qualities are most important to American voters in judging how their leaders are “dealing with the coronavirus or COVID-19 outbreak”:[3]

- “Follows the advice of scientists and other experts”; picked by 21% as most important out of 16 traits

- “Communicates truthfully with the public” (13%)

- “Acts quickly” (13%)

At least in the American context, the premium appears to be on data-driven, clearly and credibly communicated, quick action. It is notable that some other leadership attributes that often emerge as important in political surveys are not among the top responses, such as “compassionate and able to offer comfort in crisis.”

One reason President Trump’s initial rise in overall job approval and COVID-19 job approval may have quickly dissipated is that majorities of those who identify these as the most important leadership qualities also say that Trump lacks these very qualities. A 68-32% majority among those who say it is very important that a leader “follows the advice of scientists and other experts” say this does not describe Trump well. A 60-38% majority rejects the idea that Trump “communicates truthfully to the public,” among those who say this is a key quality. A 56-44% majority of those who want their leaders to “act quickly” say that Trump fails to do so.

There is unfortunately little comparable data from other countries. Yet there is scattered evidence about what leadership qualities on COVID-19 publics are looking for around the world.

The April 2 edition of Pandemic PollWatch found there was evidence worldwide of publics preferring stronger, rather than more gradual, actions against COVID-19. That evidence included a strong cross-national willingness to trade off human rights in their countries in order to combat the virus, as well as evidence in some countries that leader job approval correlated to the “stringency” of the country’s response to the pandemic, as measured by a “COVID-19 Stringency Index” developed at Oxford University.[4]

Global polling also suggests a cross-national preference for moving quickly. For example, recent surveys show that majorities or pluralities feel their governments have moved too slowly against the virus, rather than too quickly, in France (68-32%), Finland (34-2%), Japan (75-2%), and Paraguay (84-16%).[5]

South Korea’s national vote on April 15 provides an important first test of how COVID-19 can impact ruling parties – and voter turnout

The dominant focus of these weekly reports is on the political implications of the coronavirus pandemic. While global public opinion polls provide important clues about political implications, the most important political data will come from election results themselves.

Yesterday’s legislative elections in South Korea marked the first time a country has voted for national leaders since the WHO declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic on March 11. The results provide important insights into how the pandemic may be shaping global opinion and politics.

The election resulted in a landslide victory for President Moon Jae In’s Democratic Party. The party and its smaller affiliate earned 60% of the total vote, winning 180 seats – an absolute majority in the 300-member National Assembly, and a significant improvement on the 123 seats the party won in 2016. These results show that, at least in certain cases, the COVID-19 pandemic may politically benefit incumbent leaders – although it is far from certain that will happen globally.

The result was not pre-ordained. President Moon stumbled early as the COVID-19 crisis began. Hundreds of thousands of South Koreans signed a petition at the end of January criticizing him for not banning visitors from China, and over a million signed a petition calling for his impeachment in February. Regular tracking from Gallup[6] shows that the Democratic Party’s projected vote share reached a low point of 34% during the last week of January, as the crisis began to emerge in full, and the President’s approval rating hit a low of 41%.

In those early days of the crisis, the opposition United Future Party’s campaign – with the slogan “We can live only when we change the government!” – resonated with voters. According to Gallup in mid-February, voters were split on whether they should vote for ruling party candidates to support the current government (43%) or opposition party candidates to place a check on it (45%).

Two dynamics appear to have helped turn the tide in favor of the ruling party. First, the country’s leadership began doing more to consult experts and implement an aggressive regime of testing and contact tracing, allowing them to focus efforts on sick people and to “flatten the curve.” Second, the opposition United Future Party failed to offer an alternative set of policies for dealing with the crisis.

As the election approached, the government’s more stringent measures to combat the coronavirus began to take hold, show results, and receive international praise. Criticism from the opposition became less effective. The Democratic Party’s predicted vote share improved 10 points since that last week of January and the President’s approval rating improved 16 points over the same period.

By April 8th, polls showed 51% wanting to vote for ruling party candidates in order to support the government – close to the landslide figure that the incumbent party ultimately won. Even the leader of the opposition United Future Party, Hwang Kyo Ahn, lost in the district he ran for and will now step down as party president.

The South Korean elections also offer important insights into the dynamics of voter turnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. South Korea has been hit hard by the virus. As of this writing, South Korea has diagnosed 10,613 cases of COVID-19 (about 200 cases per million people), and has recorded 229 deaths. Nearly seven out of ten South Koreans are “very” or “somewhat concerned” about the coronavirus.

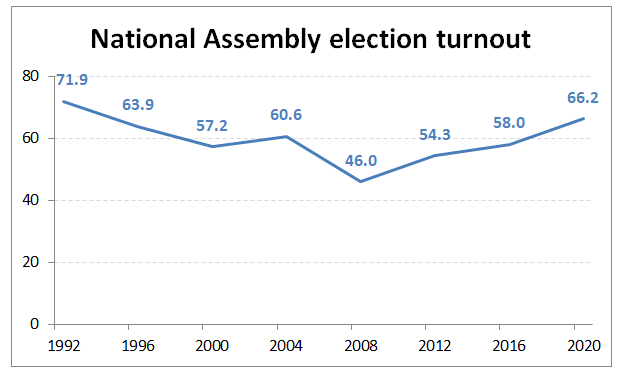

Despite COVID-19’s incidence and impact in South Korea, however, the country not only managed to hold elections, but also to achieve much higher turnout than usual. In all, as Figure 3 shows, 66% of all eligible voters cast a vote – the highest turnout the country has seen in such elections for 28 years.

Figure 3: Percent of eligible voters casting ballots in South Korean National Assembly elections, 1992-2020

Several reports[7][8][9] have noted the factors that contributed to the high turnout, including:

- An embrace of early voting – first introduced in South Korea in 2013, this ultimately accounted for over a quarter of the vote, more than double what it was in 2016.

- Painstaking measures at the polling stations to ensure voting was safe for anyone who turned out— this included tape markings on the floor to demarcate a safe distance for those in line, compulsory mask-wearing, and poll-workers at the doors of voting stations to take voters’ temperature. Anyone with a fever was directed to a separate area to vote. Voters were given disposable gloves for handling their ballots and were provided with hand sanitizer.

- Special measures for those who were sick or in quarantine— such individuals were escorted to separate voting booths, which were then sanitized by poll workers in full protective gear. Those hospitalized or unable to leave quarantine were able to vote by mail if they had applied by late March.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., changes in exercise routines as a result of the pandemic) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations.

Our first four installments of Pandemic PollWatch, on March 20, March 27, April 2, and April 9, reviewed a total of 326 polls from 82 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling on Hong Kong). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 94 polls, covering 40 countries and geographies, increasing the total number of geographies with reviewed public opinion data up to 87. Links to all new polls reviewed for this edition are listed in the Appendix. The Appendices for the first four editions, all available here, include links to all the earlier polls reviewed. As the Appendix notes, polls reviewed here vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] For both Figures 1 and 2, data only compiled for countries having week-on-week public polling on the question shown. Countries only counted as showing an “increase/decrease” if the week’s change is at least 3 percentage points. Average for change in level of concern is not population-weighted across countries. Question wordings may differ somewhat across countries and weeks. In both Figures 1 and 2, the data for the week ending April 9 has been revised slightly from last week’s edition of PollWatch, to reflect late-arriving data.

[3] The full results for this question are as follows:

“Thinking about the characteristics of leaders, please choose FOUR of the traits below that are the most important for dealing with the coronavirus or COVID-19 outbreak; put the most important trait as number one, the second most important trait as number two, and so on.” (figures are %s)

[4] Pandemic PollWatch featured a discussion of the Oxford Stringency Index in its April 2 edition. As we noted then, the Stringency Index enables researchers to track and compare government responses to the COVID-19 outbreak. It is an indexed average of the severity of seven types of government response: school closures, workplace closures, public event cancellations, public transport closures, public information campaigns, internal movement restrictions and international travel controls. Each type of response is scored, then averaged, to form the overall Stringency Index for a given country. Hale, Thomas and Samuel Webster (2020). Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. Data use policy: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY standard. More at: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/oxford-covid-19-government-response-tracker. GQR sees both strengths and limitations to this Index, and is not endorsing it, only noting it and using it as an early variable for inquiry. For example, one can question whether it makes sense to equally weight all seven factors that are averaged. The seven factors also do not capture important elements such as national testing protocols.

[5] There were significant differences in question wording across these surveys. France: Elabe, April 15, 2020, https://elabe.fr/coronavirus-vague9/; Finland: HS-Gallup, April 5, 2020, https://www.hs.fi/politiikka/art-2000006464508.html; Japan: NHK, April 13, 2020, https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20200413/k10012384571000.html; Paraguay: MultiTarget, April 7, 2020, http://multitarget.com.py/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ENCUESTA-MULTITARGET-PARAGUAY-COVID-MARZO-2020.pdf

[6] Gallup, April 8, 2020, https://www.gallup.co.kr/gallupdb/reportContent.asp?seqNo=1098

[7] Foreign Policy, April 13, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/13/south-korea-first-national-coronavirus-election/

[8] CNN, April 16, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/15/asia/south-korea-election-intl-hnk/index.html

[9] BBC, April 16, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52304781

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Morocco

- North Macedonia

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The polls reviewed for this edition of Pandemic PollWatch (with links in all possible cases) are listed below. The four earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

Australia

- Essential; April 9-12, 2020; 1,068 respondents; online; link

- SORA; April 1-6; 1,554 households; telephone; link

Brazil

- IBOPE Inteligencia; April 2020; 1,500 respondents; link

- Datafolha; April 1-3, 2020; 1,511 respondents; telephone; link (media); link (economic); link (daily life changes)

- Datafolha; April 1-3, 2020; 1,040 respondents (Sao Paulo and Rio); cell phone; link

Canada

- Leger/Association for Canadian Studies; April 9-12, 2020; 1,508 Canadian and 1,012 American adults; link

- Ipsos; March 2020; 70,955 US adults & 1,471 Canadian adults; link

Chile

- Activa Research; April 3-9, 2020; 1,270 respondents; online; link

- Cadem; April 8-9, 2020; 709 respondents; telephone; link

Czechia

- Ipsos; March 27-29, 2020; 1,033 adults; online; link

Denmark

- Voxmeter; March 30 – April 11, 2020; 1,052 adults; telephone; link

Estonia

- Turu-uuringute AS; April 11, 2020; 2,039 15 and over; phone and online; link

- Kantor Emor; March 23-25, 2020; 628 residents; link

Finland

- Yle; March 4-April 7, 2020; 3,921 adults; link

- Alma; March 20-27, 2020; 1,200 adults; online & telephone; link

- Helsingin Sanomat; April 1-2,2020; 1,053 people; link

France

- Elabe; April 13-14, 2020; 1,004 adults; online; link

- OpinionWay; April 13, 2020; 1,002 adults; CAWI; link

- OpinionWay; April 13-14, 2020; 1,018 adults; CAWI; link

- Odoxa; April 14, 2020; 961 adults; online; link

- Elable; April 6-7, 2020; 1,005 adults; online; link

- OpinionWay; April 7-8, 2020; 1,038 adults; CAWI; link

- OpinionWay; April 8-9, 2020; 1,088 adults; CAWI; link

- Odoxa; March 25-30, 2020; 3,004 adults; online; link

- Odoxa; April 8-9, 2020; 1,003 adults; online; link (masks and government); link (apps and technology); link (govt messaging)

Germany

- ZDF; April 6-8, 2020; 1,175 voters; telephone; link

- Bild; April 9-14, 2020; 2,108 adults; unspecified; link

- Speigel/Civey; April 7-14, 2020; 10,027 adults; unspecified; link

- YouGov; April 10-13, 2020; 2,073 adults; unspecified; Link

- Ludwig Maximilians University; April 1-5, 2020; 15,589 over 10-year-olds; online; link

Greece

- MRB; dates unspecified; 700 respondents; unspecified; link

- Marc; April 11-13, 2020; 1,020 respondents; telephone; link

- QED; March 21 – April 4; 1,000 15+ year olds; telephone; link

Italy

- Tecné; April 9-10, 2020; 1,000 respondents; CATI/CAWI; link

- Ipsos; April 7-9, 2020; 1,000 respondents; CATI/CAWI/CAMI; link

Japan

- NHK; April 10-13; 1,253 respondents; telephone; link

- FNN; April 11-12, 2020; 1,050 respondents; telephone; link

Mexico

- Mitofsky; March 2020; 41,865 adults; link

- El Financiero; March 13-14 and 27-28, 2020; 820 adults; telephone; link

- El Financiero; April 4, 2020; residents of Mexico City; link

Pakistan

- Gallup Pakistan; April 2020; 609 respondents; phone; link

- Gallup Pakistan and Gallup International; March 2020; 24,652 respondents; link

Paraguay

- Multitarget; March 27-April 1, 2020; 450 respondents; CATI; link

Poland

- Onet/Neurohm; April 8-11, 2020; 1,221 adults; iCode; link

- IBRiS: April 7, 2020; 1,100 adults; CATI; link

Portugal

- Universidade Católica Portuguesa/Cesop; April 6-9, 2020; 1,700 people; link

South Korea

- Polinews; April 7-8, 2020; 1,000 respondents; phone; link

- Polinews/MBC; April 7-8, 2020; 1,003 respondents; phone; link

- Gallup Korea; April 7-8, 2020; 1,000 respondents; phone; link

- Realmeter; April 6-8, 2020; 1,509 respondents; phone; link

- Korea Research Institute; April 3-6, 2020; 5,000 respondents; phone; link

- Realmeter; March 30-April 3, 2020; 2,521 respondents; phone; link

- Dong-A Ilbo; March 29, 2020; link

Spain

- CIS; March 30-April 7, 2020; 3,000 adults; landlines and cells; link

- El Periódico de Aqui; April 2-3; 2,850 respondents; unspecified; link

Sweden

- Kantar Sifo; April 2-8, 2020; 700 adults; link

Switzerland

- Swiss Broadcasting Corporation; April 3-6; 29,891 respondents over the age of 15; unspecified; link

Thailand

- Suan Dusit Poll; April 7-10; 2,970 adults; unspecified; link

Turkey

- MetroPoll; March 19-27; 1,526 adults; phone; link

UK

- BMG; April 7-9, 2020; 1,541 adults; online; link

- Opinium; April 7-9, 2020; 2,005 adults; online; link

- YouGov; April 9, 2020; 2,741 adults; online; link

- ORB; April 8, 2020; 2,122 adults; online; link

- Savanta; April 8, 2020; tracker; 1,370 adults; online; link

- YouGov; April 2-7, 2020; 884 healthcare professionals; unspecified; link

- Opinium; April 3-6, 2020; 2,002 adults; online; link

- King’s College/Ipsos MORI; April 1-3; 2,250 adults; online; link

Ukraine

- Rubicon Group; March 28-April 3; 1,400 respondents; CATI; link

USA

- YouGov; April 12-14, 2020; 1,000 adults; online; link

- Civiqs; April 11-14, 2020; 1,600 adults; online; link

- Navigator; April 9-14, 2020; 1,003 registered voters; online; link

- USA Today/Ipsos; April 9-10, 2020; 1,005 adults; online; link

- Strada Education; April 8-9, 2020; 1,001 adults; online; link

- POLITICO/Morning Consult; April 10-12, 2020; 1,990 registered voters; link

- Reuters/Ipsos; April 13-14; 2020; 1,111 adults; online; link

- CBS News/YouGov; April 7-9, 2020; 2,025 adults; link

- Economist/toYouGov; April 12-14, 2020; 1,500 adults; link

- Project 538 (updated daily); February 16-April 13; link

- Bovitz Inc (Funded by National Science Institute and Northwestern University); March 13-ongoing; 5,842 respondents; link

- ABC News/Ipsos; April 8-9; 512 adults; online; link

- Loyola Marymount University; March 23-April 8; 2,000 respondents; online; link

- Fox News; April 4-7; 1,107 registered voters; phone; link

- Hart Research/CNBC; April 3-6; 804 adults; link

- The Economist/YouGov; April 5-7, 2020; 1,500 adults; online; link

- Data for Progress; April 5-6; 2,644 likely voters; online; link

- SSRS/CNN; April 3-6, 2020; 1,002 responses; phone; link

- Quinnipiac Polling; April 2-6; 2,077 self-identified registered voters; phone; link

- Reconnect Research; March 27-April 3; 5,198 adults; RICS; link

- Baldwin Wallace University; March 17-25; 2,995 registered voters; online; link

- Pew Research; March 19-24; 11,537 adults; online; link (link to data and toplines)

- Ipsos; March 2020; 70,955 US adults & 1,471 Canadian adults; link

Vietnam

- Infocus Mekong Research; April 14, 2020; 500 respondents; unspecified; link

Multi-country

- Kekst CNC (UK, US, Germany, Sweden); March 30 – April 3; 4,000 adults; unspecified; link

- Oliver Wyman (Australia, Germany, Singapore, Spain, UK, USA); March 21-27, 2020; 1,000 in US and 500 in others; online; link

- Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (Argentina, Germany, South Korea, Spain, UK, US); March 24-April 7, 2020; 8,522 adults; online; link

- Inter-American Development Bank (Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, Panama, Peru, Uruguay); Ongoing; Ongoing; Online; link

- YouGov (Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Indonesia, India, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Norway, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, UAE, UK, USA, Vietnam); ongoing; ongoing; online; link

- Ipsos (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela); March 27-April 6; 353 opinion leaders; online; link

- Morning Consult (Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Mexico, UK, US); March 24, 2020; 315-616 daily interviews/country; unspecified; link