The approach of the new school year is driving a global debate about how societies should provide for children’s education as the coronavirus pandemic continues. In most countries, majorities are not comfortable about sending their children back into in-person classrooms, even though there are concerns about remote learning and the economic impact of school closures. Many parents worry about the ability of schools to enforce social distancing among students. As with most aspects of the pandemic, the debate over school safety and reopening has become uniquely polarized along partisan lines in the US.

This edition of Pandemic PollWatch summarizes global polling on attitudes toward school reopening, and also examines the role of the coronavirus pandemic has had in a series of recent elections, with a particular focus on the July 5 election in the Dominican Republic. There was only one major national leadership election during the first three months of the pandemic (in South Korea, on April 15), but in the second half of 2020 there are dozens (including the US November election). We are tracking them closely to determine the impact the pandemic is having on global electoral politics.

This is the fifteenth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- Most of the world is uneasy about sending children back to in-person classrooms; despite concerns about the efficacy of remote learning and possible economic impacts on children not returning to classrooms, high shares worry about the ability of schools to enforce social distancing and to take other actions needed for safety.

- In 5 global elections held since the last edition (Dominican Republic, Poland, Croatia, Singapore, and North Macedonia), ruling parties emerged victorious in 4 of them; turnout was historically high in Poland’s presidential run-off election, but lower than in previous races in Croatia, North Macedonia, and the Dominican Republic (voting is mandatory in Singapore).

- The Dominican Republic election was notable for several reasons: it was one of the few cases since the pandemic of an opposition party emerging victorious, and also one of the cases in which the coronavirus was not a dominant issue; rather anger over corruption was the main driver of the victory by the Modern Revolutionary Party (PRM) and its presidential candidate, Luis Abinader.

Major Insights

Most of the world is uneasy about sending children back to in-person classrooms; despite concerns about the efficacy of remote learning and possible economic impacts on children not returning to classrooms, high shares worry about the ability of schools to enforce social distancing and to take other actions needed for safety.

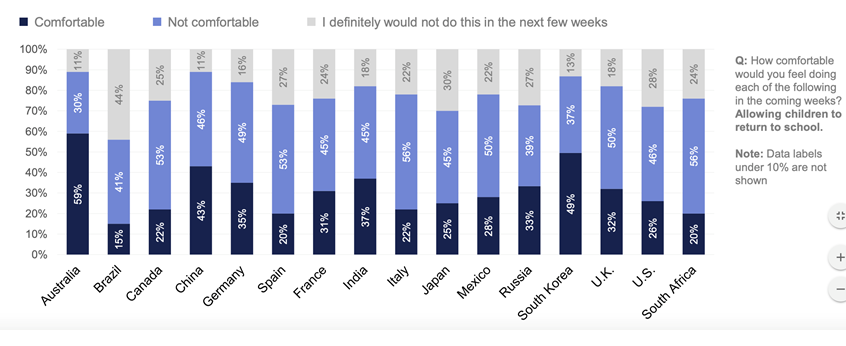

Most of the world is uneasy about sending their children back to school. In the majority of countries with polling data on this set of questions, only a minority feel confident about doing so. As Figure 1 shows, a May 10 Ipsos poll across 16 countries finds that in only one of these countries – Australia – does a majority feel comfortable allowing children to return to school in the coming weeks. The US – where 26% feel comfortable with children returning to school – ranks 10th of the 16 countries.

Figure 1: % who feel comfortable allowing children to return to school; 16 countries (Ipsos)

Similarly, a June 1 Kantar poll of the G-7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, US) finds that only 35% of the publics across these countries are “very” or “fairly comfortable” sending their children to school in the next few weeks, compared to 40% who are “very” or “fairly uncomfortable.”

Additional countries show similar concerns about the safety of resuming in-person schooling, including:

- Belgium: An iVox poll of Belgian parents in early May finds 54% believe it is not safe for students to return to class.

- Chile: A June 12 Cadem poll finds that only 5% of Chileans support continuing school in-person (down from 17% in early May), with 34% wanting to end the schoolyear early, and 57% wanting to continue courses online.

- Israel: A June 9 Bezeq Israel survey finds that only 19% of Israeli Jews support keeping all schools open, although 45% support only closing schools with coronavirus cases. Support for keeping schools open is even lower among Arab Israelis, with 16% wanting to keep all schools open, and 24% wanting to close only schools with coronavirus cases. Among Arabs, fully 48% support closing all schools and shifting to online classes, compared to only 27% among Israeli Jews. (There is some evidence that Israel’s re-opening of schools in May might have contributed to a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases.)

Even in some countries where public support for government handling of the pandemic is high, resistance to returning to in-person schooling is high. In Australia, for example, a May 5 Essential Research poll finds a 41-36% plurality agreeing that “even if schools in my state are open, I will still choose to keep my children home because of the COVID-19 outbreak.”

In the UK, where support for the country’s coronavirus policies is much lower than in Australia, 61% of respondents say “it is unsafe to send children in some classes back to school in June,” according to a June 11 ORB poll. In the US, where there is also low confidence in the national government’s coronavirus policies, a July 6 Russell Research poll finds that only about half of parents likely will have their children attend school in-person in the fall – 44% of parents of high school students, 50% for parents of kindergarten and elementary school students, and 51% for parents of middle school children.

Part of this resistance stems from health concerns and doubts that schools can maintain social distancing. A May 5 Elabe poll in France finds 81% doubt that primary schools can maintain sufficient social distancing among students. Levels of doubt are lower – but still a majority – concerning social distancing in high school (51%) and middle school (58%). In the UK, a strong 68-14% majority in a May 22 JL Partners poll say that children are safer at home than at school. A May 18 Quinnipiac University poll finds a 52-40% majority believe it will be unsafe rather than safe “to send students to elementary, middle, and high schools in the fall.” Concern is higher among women (57-34% unsafe), city residents (58-33%), and respondents under age 35 (62-35%). As with many coronavirus-related questions in the US, results also split on partisan terms, with high concern among Democrats (73-20% unsafe), but low among Republicans (25-68%).

There is also concern about the efficacy and increased burdens from remote learning. A May 31 U-Report survey of students in Bolivia, conducted after in-person classes had been cancelled, found that 47% were learning less (“nothing” or “almost nothing”) through their online lessons, compared to in-class lessons. In the Essential Research poll noted above, Australians worry about the burden on teachers, with a 52-21% majority saying “it’s unreasonable to expect teachers to prepare separate lessons for children who are learning remotely and for children who still attend school.”

Teachers, too, have concerns about in-person learning, as a May 21 USA Today/Ipsos poll finds that most American teachers feel that it will be difficult to enforce social distancing in schools. Fully 1 in 5 of these teachers say it is likely that they would not return to teaching if their school were to reopen.

At least in some countries, there is skepticism that a return to school is necessary for economic recovery. In the May JL Partners poll in the UK, as the country was deciding whether to re-open schools for the end of the term, a 52-30% majority say “it is not important for the economy that schools re-open in June.”

As we have noted in previous editions, worry about a second wave of COVID-19 is high in most countries, and a second wave could elevate concerns about in-person schooling even further. A June 15 Axios/Ipsos poll in the US, for example, finds 77% of parents would be very or somewhat likely to keep their child home from school or day care in the event of a second wave.

Despite these concerns, there are still fairly strong expectations of schools reopening in the fall. In the US, a May 20 USA Today/Ipsos poll finds that 63% of parents believe it is very or somewhat likely that schools in their area will reopen in the fall, regardless of whether or not they are planning to send their children. Expectations of reopening may be higher in much of Europe, where fears about COVID-19 are generally lower.

Five global elections since the last edition of Pandemic PollWatch – in the Dominican Republic, Croatia, Singapore, Poland, and North Macedonia – show incumbent leaders holding onto power in most places, and a mixed pattern of potential impact of the pandemic on voter turnout.

As we have previously noted, the most important barometer of the political impact of the coronavirus pandemic is not polling, but election results. During the first several months of the pandemic, there was only one major global election, in South Korea on April 15 (we profiled those results in our 5th edition). But the second half of 2020 is seeing dozens of major elections, and we are following them closely to analyze the impact of the pandemic.

Since our July 3 edition, there were five major elections globally: the July 5 general election in the Dominican Republic; the parliamentary election on July 5 in Croatia; the July 10 general parliamentary election in Singapore; the July 12 second-round (run-off) presidential election in Poland; and the July 15 parliamentary election North Macedonia.

This set of races generally favored incumbent leaders and parties. In four of the five elections – Croatia, Singapore, Poland, and North Macedonia – the ruling party emerged victorious. Croatia’s ruling center-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) gained 5 seats. In Singapore, the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) won 61% of the vote share. In Poland, President Andrzej Duda of the ruling Law and Justice Party (PiS) won a narrow 51-49% second-round victory over Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski. In North Macedonia, Prime Minister Zoran Zaev’s coalition lost eight seats but emerged with the highest vote share.

Of the five contests, only the Dominican Republic saw a victory for the opposition. We analyze that race in more detail below.

We have noted that the pandemic tended to provide somewhat of a boost for incumbent leaders and parties; this was especially the case in the early days of the pandemic, and that boost has often endured if leaders show competence and stringency in handling the outbreak. The success of the incumbent parties in most of these races would appear on the surface to support that pattern. But COVID-19 was not the dominant issue in any of the races, and there were important details below the surface in many of them:

- In Croatia, the government has not performed strongly on the pandemic, and support for the opposition rose alongside the number of COVID-19 cases.

- Singapore won international acclaim for its early steps to combat the pandemic, but the end of April saw a rise in the number of cases, as crowded migrant worker dormitories emerged as an overlooked hotspot. As the election approached, confidence about battling the pandemic waned; in late May, a Blackbox poll showed 28% of Singaporeans expecting the daily number of COVID cases to decrease in the next two weeks; by the end of June, that number had dropped to 14%. Ultimately, while the ruling PAP retained a majority, the opposition achieved the largest presence in Parliament since 1966.

- In Poland, the government is generally seen as having done a competent job in combatting the pandemic. That helped permit President Duda to stick to tried-and-true messaging of the ruling Law and Order (PiS) party: presenting himself as a defender of Catholic values, including opposition to LGBTQ rights, and a strong proponent of the social benefit programs that have supported those in poorer rural areas (PiS’s base of support).

- As we note below, in the Dominican Republic, the coronavirus was not a dominant issue, with more of the electorate’s attention focused on corruption and the economy.

These elections saw a mixed impact on voter turnout. We have noted that the coronavirus pandemic does not appear to be uniformly depressing voter turnout worldwide. In some cases, like the April 15 South Korean elections, turnout has actually been higher than usual, with voters there turning out at rates not seen in almost three decades. The new set of elections offers a mixed verdict on turnout.

Poland’s turnout was very high, at 68%. Despite strong concerns about a second wave of COVID-19 – 76% according to a July 3 poll from ARC Rynek i Opinia – the run-off election saw the highest level of turnout since the country’s second Presidential election in 1995. The high turnout almost certainly owed to the closely divided and intensely waged contest, but also may have reflected public confidence about the country’s efforts to combat the coronavirus.

There were notable drops in turnout, however, in the contests in the Dominican Republic (55%, down from 70% in 2016), Croatia (46%, down from 52% in 2016), and North Macedonia (51%, down from 67% in 2016). Singapore, where voting is mandatory, saw turnout over 90%.

The Dominican Republic elections offer an important reminder that the pandemic is sometimes not a dominant issue.

The sweeping victory by the opposition in the Dominican Republic stands out as an exception to the general pattern of incumbent victories in the coronavirus era; it also stands out for the degree to which COVID-19 was not a dominant issue.

The July 5 general elections put an end to 16 years of rule by the Dominican Liberation Party (PLD). Opposition candidate Luis Abinader of the Modern Revolutionary Party (PRM) capitalized on dissatisfaction with the PLD to win the presidency in the first round over PLD candidate Gonzalo Castillo, by a decisive margin of 53-38%. The PRM also picked up majorities in both the lower and upper chambers of Congress.

Although cases of and deaths from COVID-19 are increasing in the Dominican Republic, setting new records in July, the government’s handling of the pandemic was not a driving factor in the elections. Between two GQR polls for Dominican newspaper Diario Libre – one in February before their first case of the virus and one in mid-June – Abinader’s lead over Castillo changed by just 1 point among likely voters.

Indeed, Abinader appeared to win despite general popular support for the efforts by the PLD government to combat the virus, including a state of emergency that lasted from March 19 to June 30. GQR’s June 16 survey shows 65% of Dominicans actually approved of the government’s handling of the coronavirus.

Instead, the dominant issue that ended PLD rule was deep frustration with corruption. According to GQR’s June survey, corruption and unemployment were the top concerns on people’s minds. Health care came in third on the list. Even with COVID-19 cases skyrocketing, Dominicans were more concerned with corruption than health. Among those who listed corruption as one of their top two concerns, Abinader led Castillo by 61-24%.

As noted above, turnout in the July 5 voting was only 55%, compared to 70% in the 2016 general election, and this was at least partially due to COVID. A 57% majority of Dominicans said they were very or somewhat concerned about going out to vote due to the virus. But there was also a lack of enthusiasm for the incumbent party; only 56% of voters for the ruling PLD were absolutely likely to vote (“10” on a scale from 1-10), compared to 68% for PRM voters.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 14 installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through July 3, reviewed a total of 1,394 polls from 107 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 98 polls, covering 58 geographies, bringing our total geographies to 108. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The 14 earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.