an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

As the incidence of COVID-19 spikes again in the US, a comparative analysis of global polling underscores how much more fearful Americans are of a second wave of the disease, relative to people in other countries. Although majorities worry about a resurgence of the disease in every country with public polling on this question, concern is highest, at 85%, in the US. The fear of resurgence may be helping to fuel a general rise in concern about the disease, after weeks when that metric declined, and may be one reason that a large plurality of Americans believe most other countries are doing better than the US at dealing with the coronavirus outbreak.

This edition of Pandemic PollWatch summarizes global polling on expectations about a second wave, and also looks at the role the coronavirus pandemic is having in global elections. As we have noted, there was only one major national leadership election during the first three months of the pandemic (in South Korea), but in the second half of 2020 there are over a dozen. We are tracking them closely to determine the impact the pandemic is having on global electoral politics. Finally, this edition examines reactions to COVID-19 in Greece, where a relatively successful government response has buoyed support for the Prime Minister.

This is the fourteenth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- Majorities in all countries with public polling data worry about a second wave of the coronavirus, but concern is highest in the US, where fears are rising again as the incidence of COVID-19 spikes.

- Elections in the past 12 days in Mongolia, Malawi, France, Poland, Serbia, and Iceland provide insights on the political impact of COVID-19, including evidence that voters reward governments that respond competently to the pandemic, and that the pandemic is not generally depressing voter turnout rates.

- Greece provides an important example of how voters are rewarding leaders who demonstrate competence in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic.

Major Insights

Majorities in all countries with public polling data worry about a second wave of the coronavirus, but concern is highest in the US, where fears are rising again as the incidence of COVID-19 spikes.

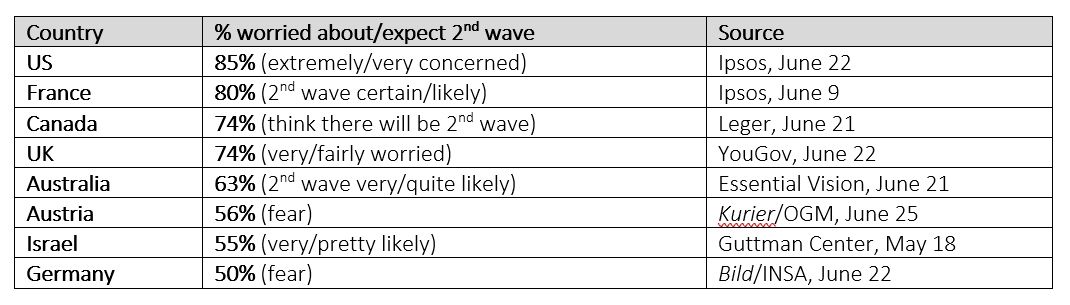

In every country with public polling data on this question, a majority expects and/or is concerned there will be a second wave of the coronavirus. As Figure 1 indicates, this is true even in countries such as Australia and Germany that have been relatively successful in dealing with the disease.

Figure 1: % in each country who expect/fear a 2nd wave of the coronavirus[2]

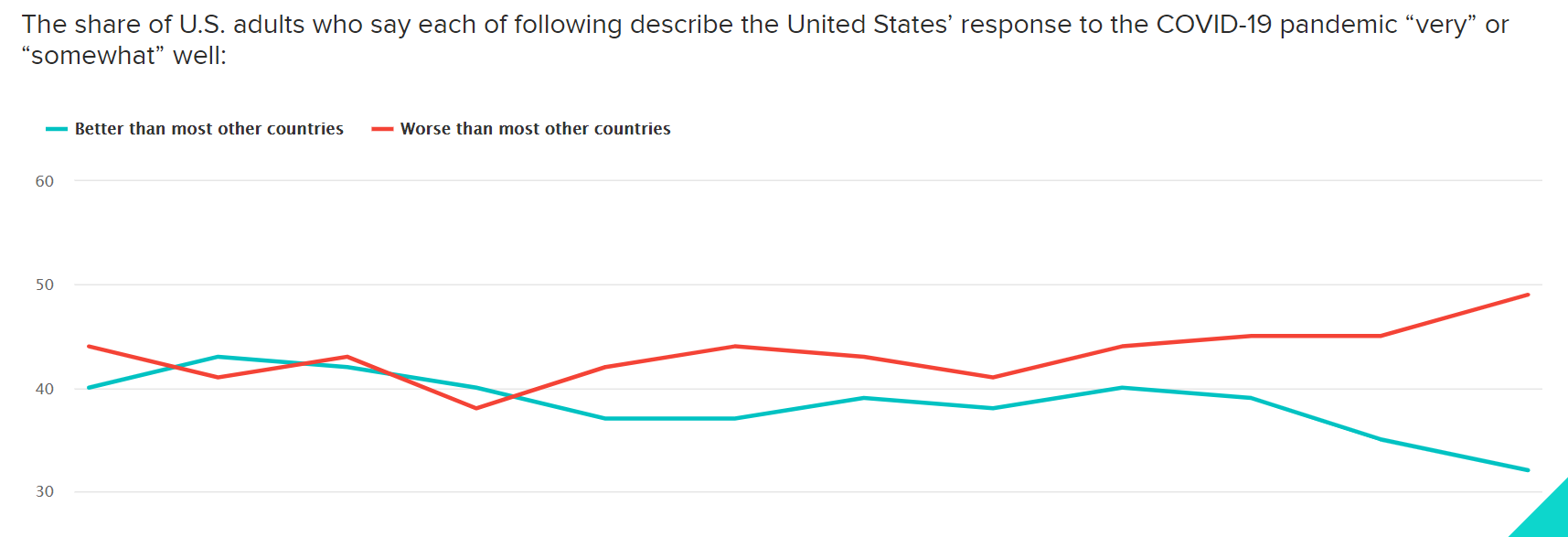

The US stands out for having the highest level of concern about a 2nd wave. That fear comes against the backdrop of a dramatic spike in COVID-19 cases over the past two weeks. As Figure 2 reveals, the rise in US cases also tracks a declining faith among Americans that their country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic is better than most other countries; on April 19 a 43-41% plurality of Americans believed the US response was better than that of most other countries, but by June 29 a 49-32% plurality believed it was worse than most other countries.

Figure 2: % who believe US response to COVID-19 better/worse than most countries (US; Morning Consult)

Morning Consult also finds that the share of Americans who are “very concerned” about the coronavirus outbreak has started to rise again. After declining from 65% to 51% between April 5 and June 14, it moved back up to 55% by June 29.

New elections in Mongolia, Malawi, France, Poland, Serbia, and Iceland provide important insights on the political impact of COVID-19, including evidence that voters reward governments that respond competently to the pandemic, and that the pandemic is not broadly depressing voter turnout rates.

Elections, not polls, provide the most important measure of the political impact of the pandemic. In the first three months after the pandemic was declared, there was only one major national election in the world, in South Korea (we profiled those results in our 5th edition). But now there have been six important elections in just the past 12 days, with dozens more to come before the end of the year.[3]

These new elections continue to suggest that voters are rewarding governments that have shown competence in dealing with COVID-19. The Mongolian election on June 24th is a good example. The government faced a potentially difficult election, conducted against the backdrop of economic stagnation and contentious election reforms. But the government had distinguished itself with a swift response to COVID-19, closing its borders with China and Russia, and canceling the national holiday of Tsagaan Sar to slow internal travel. This country of 3.2 million people has recorded only 220 cases of COVID-19 and no deaths. A May 19 Sant Maral poll found that 49% of respondents considered the government’s main success to be its reaction to the coronavirus, with the second and third responses being economic growth or improvements in the standard of living, both at 5%. That success helped drive ruling Mongolian People’s Party’s comfortable victory, as it won 62 of 76 Great Khural seats in the country’s parliamentary elections.

Recent elections show, however, that a sound response on coronavirus is not enough by itself to propel political success. France held a second round of municipal elections on June 28 (the first round was on March 15, just as the pandemic was declared, and this second round was delayed), and the results were a major disappointment for President Macron’s centrist LREM party. Like most global leaders, Macron received an initial boost in his approval ratings at the start of the crisis, according to tracking by Morning Consult. But that boost eroded with each week, and his approval rating is low in absolute terms (30%). In the June 28 balloting, LREM lost control of six cities, with incursions from both the Greens on the left, and Marine Le Pen’s National Rally on the right.

Although COVID-19 is a challenge for virtually every country, the June 23 presidential election in Malawi is a good reminder that the pandemic is not the dominant issue everywhere. There, the main issues were poverty, poor living conditions, and government malfeasance. This was a court-ordered re-do of its 2019 election, and opposition candidate Lazarus Chakwera was able to capitalize on those issues to achieve a surprisingly strong win over the incumbent president, Peter Mutharika.

The recent elections also suggest that COVID-19 is generally not depressing voter turnoutin competitive national elections. In the Mongolian election, 74% voted, the same level as in 2016. Poland’s first-round presidential election on June 28 (there will be a runoff on July 12) saw an increase in turnout; 64.5% voted in the contest where incumbent President Andrzej Duda and Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski came out in the top two spots, compared to 49% in 2015 and 55% in 2010. (Duda won 44-30%, and polls suggest the two are roughly tied for the second round ballot.) As we noted in the 5th edition of Pandemic PollWatch, South Korea’s April election saw the highest turnout in nearly 30 years. Malawi is a partial exception, with turnout in its presidential contest down 9 points from the nullified 2019 contest; but turnout was still very high, 65%. Turnout was also down in Iceland’s June 27 presidential vote and in Serbia’s June 21 parliamentary elections, but in both cases the races were not competitive (indeed, in Serbia, the opposition boycotted the contest).

Greece provides an important example of how voters are rewarding leaders who demonstrate competence in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic.

Recent editions of Pandemic PollWatch have begun to examine specific countries and the way in which their response to the coronavirus pandemic is shaping their national politics; this edition examines Greece. Greece’s record on the pandemic is mostly positive: as of July 3rd, it has seen 3,432 cases of COVID -19 and only 191 deaths, the fourth-lowest death rate in Europe. Greece’s experience bolsters the general pattern that leaders who demonstrate competence in dealing with the pandemic tend to see political gains.

There was little at the beginning of the pandemic to suggest Greece would succeed in battling the disease. Greece had just recovered from an economic crisis. It had the fifth-highest elderly population in the world. It had only nine intensive care beds per 100,000 people, compared to America’s 30. It had over 42,000 people living in refugee camps on the five Greek Aegean islands.

But the government of Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, who assumed office in July 2019, was able to use a technocratic, data-driven approach that led to both epidemiological and political success. Even before the first COVID-19 death on March 12, the government canceled Patras Carnival, the biggest event in Greece. In the two days after the first coronavirus death, the government closed non-essential shops and beaches. By March 23, it imposed a general lockdown

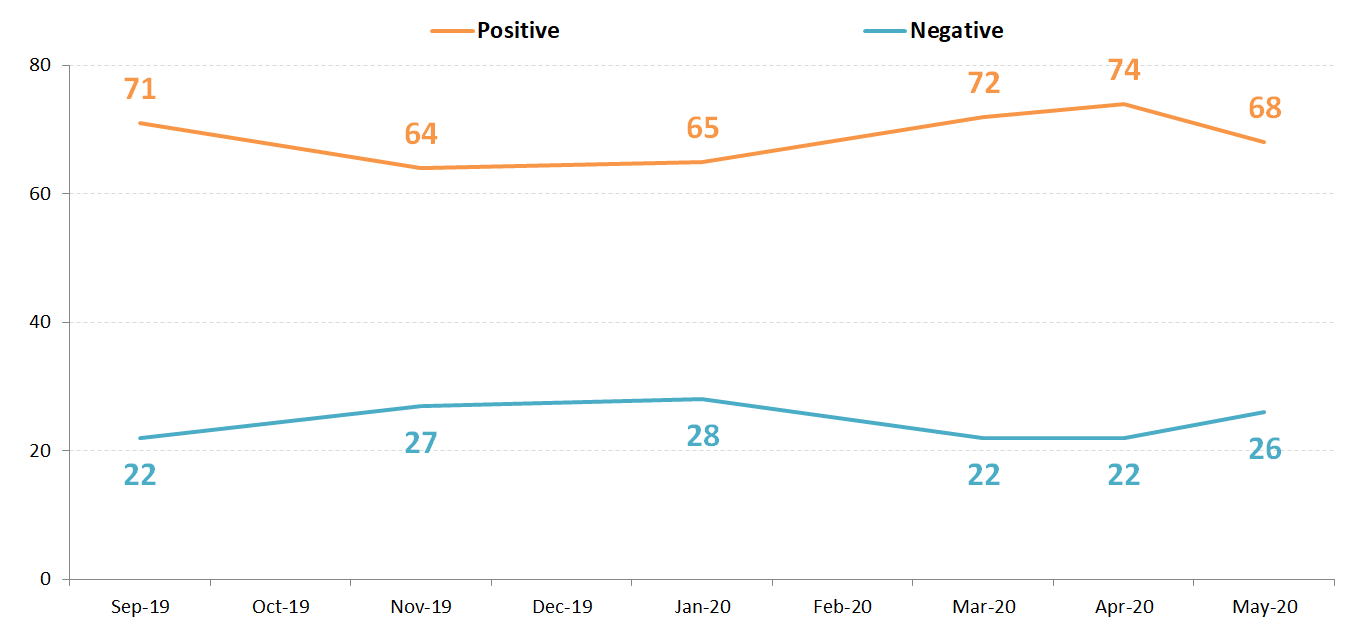

The public registered strong support for these decisive steps. Just after cases peaked on April 21, Metron Analysis found that 87% approved of the government’s handling of the pandemic. By June 3, a Pulse poll found the figure was down to 75%, but still remarkably high in a country that has often been fractured and reserved in approval of its leaders. PollWatch has noted that most global leaders received early bumps in their approval ratings after the pandemic was declared, but also mostly saw those gains erode. Mitsotakis, by contrast, has been able to maintain his very high approval ratings, now at 68%, as Figure 3 (based on data from Metron polling) shows.

Figure 3: Approval rating for Greek PM Mitsotakis (Metron polling)

Challenges lie ahead for the Mitsotakis government as it reopens for the summer tourist season. A KAPA poll in late April found unemployment as the top and rising concern. An About People poll on May 18 found 62% expect the economic consequences of the pandemic to last two years or more.

However, polling suggests that citizens have high confidence in the administration to reduce the virus’s impact on the economy. The June 3 Pulse survey found that 54% of people approve of the government’s economic measures, and a Metron Analysis poll from May 27 showed that 64% think that the country is moving in the right direction.

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 13 installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through June 18, reviewed a total of 1,246 polls from 107 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 148 polls, covering 52 countries. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] As noted, dates and question wordings differ across polls.

[3] These include:

- July 5: Croatia, Parliamentary

- July 5: Dominican Republic, General

- July 10: Singapore, General

- July 12: Poland, Presidential Runoff

- July 15: North Macedonia, Parliamentary

- July 19: Syria, Parliamentary

- August 5: Sri Lanka, Parliamentary

- August 9: Belarus, Presidential

- August 12: Bougainville, Presidential

- August: Ethiopia, Parliamentary

- August 30: Montenegro, Parliamentary

- September 6: Bolivia, Presidential Re-Run

- September: Jordan, Parliamentary

- October: Tanzania, General

- October 4: Kyrgyzstan, Parliamentary

- October 11: Lithuania, Parliamentary

- October 18: Guinea, Presidential

- October 25: Ukraine, Local

- October 25: Chile, Referendum

- October: Georgia, Parliamentary

- October 31: Côte D’Ivoire, General

- November 1: Moldova, Presidential

- November: Somalia, Parliamentary

- November 3: USA, General

- November 8: Burma/Myanmar, General

- November 22: Burkina Faso, Legislative, Presidential

- December: Egypt, Parliamentary

- December: Romania, Parliamentary

- December 7: Ghana, General

- December 8: Liberia, Referendum, Senatorial

- December 8: Venezuela, Parliamentary

- December 27: Central African Republic, General

Source: National Democratic Institute

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The 13 earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.