an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

The coronavirus has transformed global politics in many ways — raising public fears, giving many leaders an initial rise in favorability ratings, fueling tensions between countries, and more. Yet in the months since the pandemic started there has only been one major national election — in South Korea, on April 15.[1] The remainder of 2020 will see over a dozen other elections (including in the US in November), starting this Sunday in Serbia, and these contests will reveal a great deal about the political impact of the pandemic. Does it mostly help incumbents or challengers? Does it tend to shift politics to the left or the right?

This edition of Pandemic PollWatch starts a series of country case studies, looking at how the coronavirus is affecting partisan and electoral politics in countries that have upcoming elections. This edition focuses on Brazil and India, both of which have sub-national elections scheduled for the fall. The edition also looks at the impact of the pandemic on global views about immigration, and provides global tracking updates on attitudes toward the process of economic reopening.

This is the thirteenth in a series of regular papers from GQR analyzing all globally available data on opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[2] Earlier editions are here. Major insights in this edition include:

- Polls suggest publics worldwide are beginning to feel slightly more comfortable entering public spaces, but most remain cautious.

- Although the pandemic triggered a strong desire in many countries to restrict immigration, it is not clear how long-lasting that reaction will be, or whether it will alter the underlying politics of immigration.

- Brazil has local elections scheduled for October; COVID-19 has helped to reduce support for President Jair Bolsonaro, partly reflecting his populistic approach to the pandemic.

- India also has a major state election this fall; Prime Minister Narendra Modi has earned better marks for his handling of the coronavirus pandemic, but rising rates of infection and death may change that.

Major Insights

Polls suggest publics worldwide are beginning to feel slightly more comfortable entering public spaces, but most are remaining cautious.

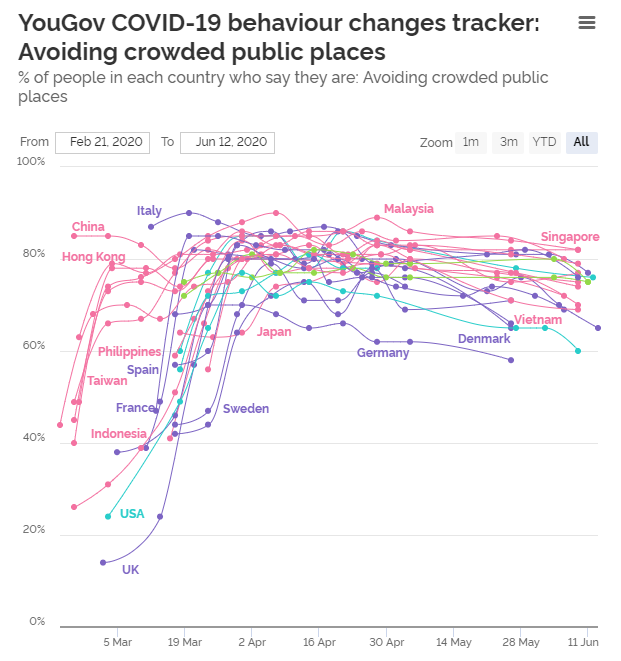

After the coronavirus outbreak was declared a pandemic in mid-March, there was a global spike in the share who said they were “avoiding crowded public places.” Now, with many countries entering a process of reopening, those numbers are beginning to decline, but very slowly. As Figure 1 shows, out of 18 countries with YouGov data on this question since June 5, 10 show a decline of at least 3 points (and an additional 5 decline by 2 points) on “avoiding crowded public places.”

Fig 1: % avoiding crowded public places (YouGov)

In Canada, an Angus Reid poll shows 57% of Canadians are staying away from public places less than they were at the start of the pandemic.

In a June 5th poll conducted by Russell Research, majorities in the US are still avoiding most non-essential activities, but there are signs of a thaw. In a list of 24 different activities that involve going out in public, people are 8 points less likely on average to avoid them compared to four weeks prior.

The British appear more cautious. In a June 12 Opinium UK poll, respondents show only marginally more comfort (three points or less) from a month ago when it comes to using public transit, eating out at a restaurant, going to the gym or a pub, or working in an office. Only “going to a café” shows marked improvement, with British respondents feeling 9 points more comfortable than a month earlier.

Although the pandemic has led to restrictions on immigration in many countries, it is not clear how long-lasting that reaction will be, or whether it will alter the underlying politics of immigration.

The coronavirus has triggered worldwide restrictions on travel and immigration. With most publics registering high concern about contracting the virus, many countries have closed their borders – including some of the most open borders in the world, like those between the US and Canada, and those between many EU countries. It is less clear how extensively or permanently the pandemic will change the politics of immigration. Long-term impacts on this issue will be important, as immigration has been pivotal in elections and political debates across many major countries, from the 2016 US election (e.g., Trump’s pledge to build a wall on the Mexican border), to the UK’s Brexit referendum, to a range of European states.

There is little question that publics in many countries initially supported restricting or fully shutting their borders in response to the pandemic. YouGov tracking polls found that, by the end of March, 17 of 19 countries surveyed showed majority support for “stopping all inbound international flights from countries with confirmed cases of coronavirus.” An April 26 Washington Post poll found 65% support for temporarily blocking nearly all immigration into the US during the coronavirus outbreak; even about half (49%) of Democrats agreed.

The desire to restrict immigration came from economics as well as health. A May 11 Essential poll in Australia found a 67-12% majority favored a proposal to reduce the number of temporary migrant worker visas during the COVID-19 outbreak so that employers could give hiring preference to Australian citizens.

Yet it is not yet clear how much, or for how long, this reaction to the pandemic will reshape the global politics of migration. There has been little global polling that measures attitudes toward immigration with identical questions both pre- and post-pandemic.

Among the polling that has been done, there are some signs that the initial pandemic-based recoil from immigration may not necessarily lead to a long-term change. A June 2 CBS poll finds a 55-16% majority saying that immigration into the US makes “American society better in the long run” rather than worse.

Narrower questions on immigration in the US also call into question whether the pandemic will usher in a more restrictive mood. The June 2 CBS poll finds an 85-13% majority in favor of allowing so-called “dreamers” – undocumented immigrants who were brought into the country as children – to remain in the US under a range of conditions. The figure had not changed significantly from the 87-11% margin in 2018, before the pandemic. With the Supreme Court’s decision today to strike down the Trump administration’s proposed abandonment of “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals” (DACA), that majority could strengthen further.

In the UK, an April 2 Ipsos poll finds a 48-27% plurality believing that immigration has “a positive impact on Britain,” which is actually up from 2019, and up quite a bit since the Brexit referendum, when opinion was about evenly split. Although a 52% majority in the UK want a decrease in the number of immigrants, that figure is down from 2019 (when it was 54%) and far down from 2015, when it reached 67%.

It also may be that the pandemic has made publics in some countries more aware of the value that immigrant workers bring, particularly in the health sector. A May 26 Survation survey in the UK found more support for liberalizing immigration for health workers than for immigrants in other fields; a 48-15% plurality supported liberalizing entry rules for “NHS workers,” and a 42-17% margin favored easier entry for “health and social care workers.” By contrast, only a 38-20% plurality favored making entry easier rather than harder for “all key workers.”

Ultimately, it is too early to tell whether, how, and for how long the health and economic impacts of the coronavirus pandemic will change global public opinion on immigration. It will be an important question to monitor in the coming months.

Brazil has local elections scheduled for October; COVID-19 has helped to reduce support for President Jair Bolsonaro, partly reflecting his populistic approach to the pandemic.

As noted, over a dozen major elections around the world are scheduled between now and the end of 2020. These will reveal a great deal about the political impact of the coronavirus, and this publication will track these elections carefully.

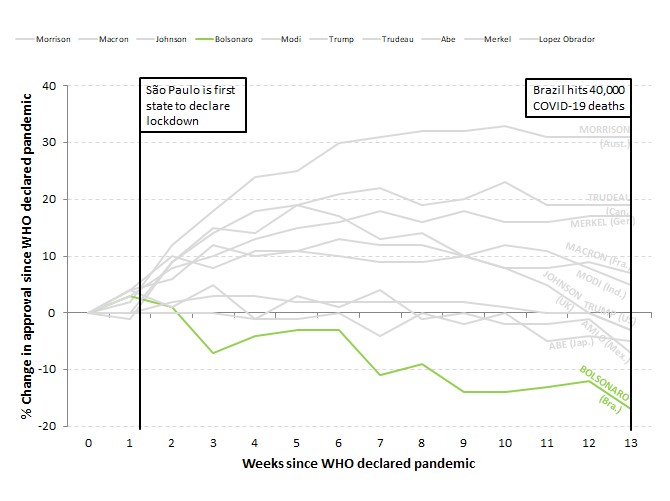

While every country’s politics is unique, the pandemic has produced some general patterns in global politics: it provided a rise in key government approval ratings at the start in most countries; leaders who have responded to the crisis with competence and science-based policies generally have seen a sustained elevation in their approval ratings; leaders who have responded with populism and weak management generally have seen their ratings fall. No country better demonstrates the last point than Brazil.

President Jair Bolsonaro, who took office at the start of 2019, met the coronavirus crisis with a decidedly populist approach. He has consistently downplayed the severity of COVID-19, touted hydroxychloroquine as a cure, flouted social distancing restrictions by attending anti-lockdown protests, called the virus a “little flu,” largely left states and cities on their own to formulate health responses, and has been accused of suppressing statistics about the extent of the virus in Brazil. As Bolsonaro tried to shrug off the threat, Brazil’s COVID-19 death toll surged to the second highest worldwide, with over 40,000 dead. It is on track to outstrip the US death toll this summer.

Polls show that the Brazilian public does not share Bolsonaro’s skepticism about the need for steps to protect their health. A Datafolha poll from late May shows that 74% of Brazilians believe that without social distancing restrictions, the country’s death toll from the virus would be higher; 65% say it is more important to maintain stay at home orders despite negative economic effects. An early-June IPSOS poll of 16 countries finds that 71% of Brazilians believe that “opening businesses puts too many people at risk,” the highest rate among all the countries surveyed. Akin to the US, disparate impacts of the pandemic along lines of race and class have spawned Brazil’s own movements of “black lives matter,” “indigenous lives matter,” and “favela lives matter.”

Bolsonaro’s denigration of the COVID-19 threat and his mismanagement of the response, combined with various political scandals since he took office, have steadily driven down Bolsonaro’s support. Out of 10 world leaders that Morning Consult has tracked since the start of the pandemic in mid-March, Bolsonaro’s overall job approval ratings have lost the most ground. As Figure 2 shows, Bolsonaro’s job approval rating has dropped 17 points since then (with approval down from 55% to 38% as of June 9).

Figure 2: Net job approval ratings for 10 world leaders (Morning Consult; data design from The Economist)

Municipal elections in Brazil, scheduled for October, may give further clues about the unpopularity of Bolsonaro’s response to the pandemic. However, the Brazilian public’s fears about COVID-19 have led 62% of them to favor postponing these local elections, according to a May 10th CNT/MDA Institute poll. If postponed, Brazil would join a number of Latin American countries—including Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, and Chile—that have rescheduled elections due to COVID-19. Furthermore, whenever the elections occur, it may be difficult to determine the impact of Bolsonaro’s handling of the coronavirus, since his party, Alliance for Brazil, may be disqualified from competing for failure to produce needed signatures for the ballot.[3]

India also has a major state election this fall; Prime Minister Narendra Modi has earned better marks for his handling of the coronavirus pandemic, but rising rates of infection and death may change that.

India has seen a different set of health and political dynamics. COVID-19 hit India relatively late. By March 24, the country had reported only a few hundred cases of the coronavirus. But with the pandemic spreading aggressively worldwide at that point, PM Modi nonetheless announced one of the strictest lockdowns in the world, according to the “Stringency Index” developed by researchers at Oxford University.[4]

The strong response, however, failed to stem the spread of the virus in India, which is home to some of the world’s most densely populated cities. About half of India’s coronavirus cases trace to just five cities: Mumbai, Delhi, Ahmedabad, Chennai and Pune.

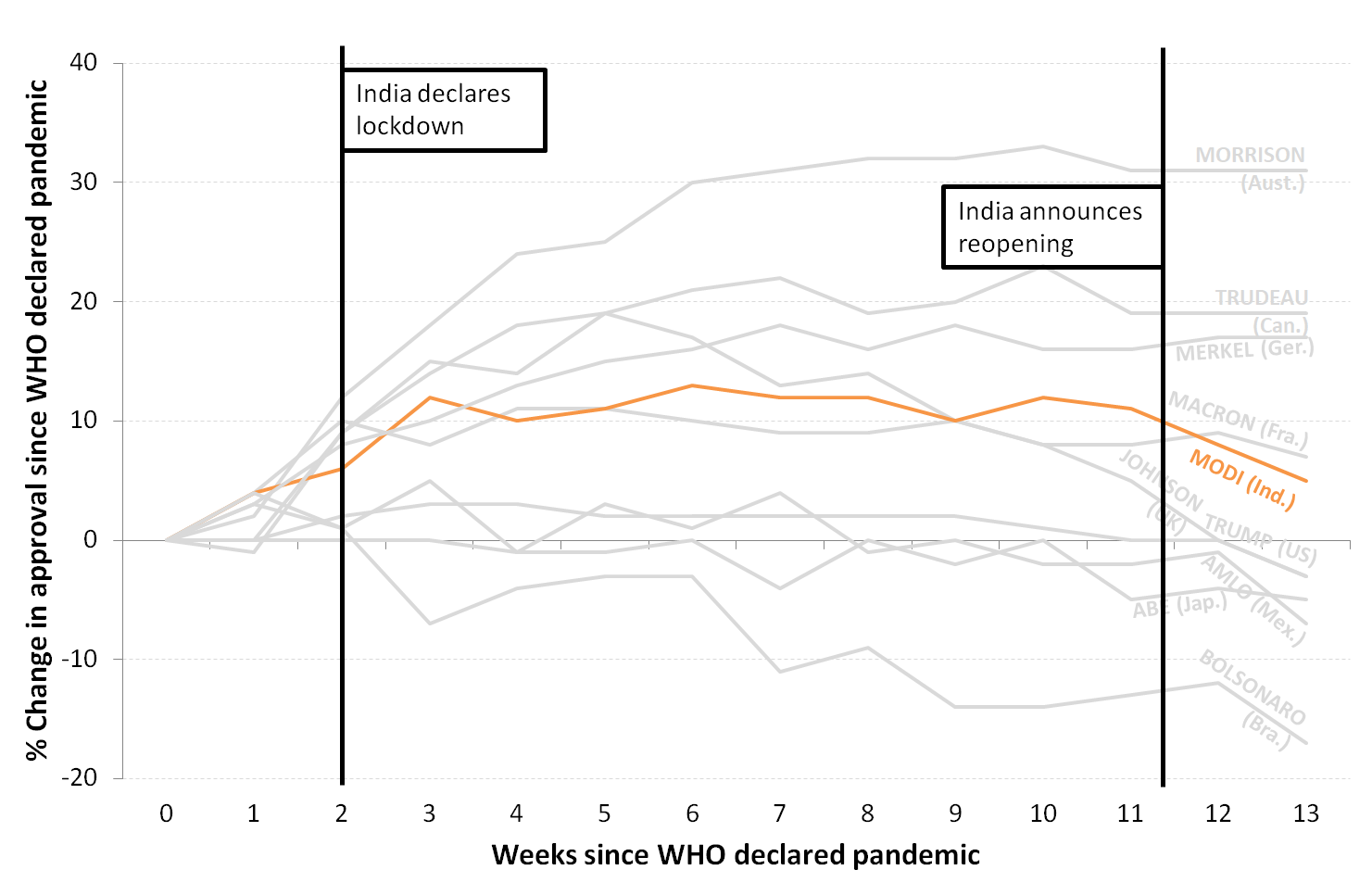

As the government implemented the national lockdown, Morning Consult data shows Modi’s already-high approval ratings initially rising further, moving from the mid-70s into the low 80s, and staying there for all of April and May.

Now more than two months after quarantine began, India has started to reopen, but it is doing so without effectively having “flattened the curve.” Large gatherings remain banned, but shopping malls, factories, places of worship, and schools are open or are set to be. Since reopening began, the country has seen a surge of new cases. June 18 marks the eighth day in a row that India has announced more than 10,000 new cases per day.

Just before the lockdown ended, 22 opposition parties met over video-conferencing to lay out their criticisms, arguing that Modi’s government has mismanaged the lockdown and failed to craft an exit strategy, leaving the poorest and most disadvantaged members of Indian society behind. They also laid out an alternative vision: 11 demands of the government for transparency and support as the country leaves lockdown.

As India’s number of coronavirus cases grows, and as the opposition ramps up criticism, Modi’s job approval has dropped over the past two weeks, and is now nearly back to where he stood at the start of the pandemic, as Figure 3 shows. But the government is hitting back, holding rallies and presenting an argument along the lines of: “although we may have fallen short… what did [the opposition] do?” His case underscores the political risks of early reopening, but also the risks if an opposition fails to offer clear alternative policies for addressing the pandemic.

Figure 3: Net job approval ratings for 10 world leaders (Morning Consult; data design from The Economist)

The first clear test of the net political effects of all this will come when India’s third-most populous state, Bihar, holds legislative elections this October or November. The state’s Chief Election Commissioner says he has “no plans” to delay this election due to virus concerns. Bihar has long faced a crumbling healthcare infrastructure, and—as in much of India—many of its citizens live on a daily wage that has been interrupted by the lockdown. The state has also struggled with a surge of infections as migrant workers returned to Bihar from dense metropolitan areas in other states. Modi’s governing alliance (the National Democratic Alliance) is starting from a strong position as the incumbent in Bihar, but the pressures of coronavirus could offer the scattered opposition a much-needed opening.

[1] Burundi held a national election on May 20, but UN monitors determined the voting was not credible and free.

[2] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing all aspects of the global opinion research. Instead, we focus on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and provide links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations. Our first 12 weekly installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through June 4, reviewed a total of 1,098 polls from 107 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong and various states and provinces). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 134 polls, covering 61 countries. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, the polls reviewed vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[3] https://exame.com/brasil/alianca-pelo-brasil-ja-admite-nao-participar-da-eleicao-de-2020/

[4] Pandemic PollWatch first discussed the Stringency Index in our April 2 edition; details about the Index are at https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Cameroon

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- Iceland

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Liberia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Senegal

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sudan

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Tunisia

- Turkey

- Uganda

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

- Zimbabwe

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The 12 earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.