an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

This is the seventh in a series of weekly papers from GQR summarizing and analyzing available data on global opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here. The major insights in this paper:

- There is a broad, although not universal, global preference for prioritizing health concerns over economic re-opening. Most countries with such data, including the US, show a clear preference for restrictions aimed at protecting public health over quick steps toward opening the economy.

- Global concern about contracting the virus continues to be mostly stable, but with a slight increase. Data this week show the highest share of countries (57%) since early March with no major change in the share of their publics who are worried about contracting the virus. But where there is a change, more countries are showing an increase in concern, with the average global level of concern up nearly 2 points this week.

- Government job approval ratings on handling COVID-19 also remain relatively stable. One third of all countries with such data show no significant change in government approval on handling COVID-19; one third show a rise in approval, and one third show a decline. Overall the average change in approval is up a half point. The US, by contrast, continues to see gradual erosion in approval of President Trump’s job in handling the coronavirus pandemic.

Major Insights

There is a broad, although not universal, global preference for prioritizing health concerns over economic re-opening

A central policy choice confronting countries around the world is how to balance the imperatives of economic re-opening with public health precautions against the coronavirus. This is not a binary choice, and some actions may advance both objectives; but there are tensions between the two objectives, which makes public preferences on the tradeoffs important.

Although the pattern is not universal, publics in most countries with polling data want their leaders to err on the side of protecting public health, even if that comes with higher economic costs. But there are important variations by country, gender, and question wording.

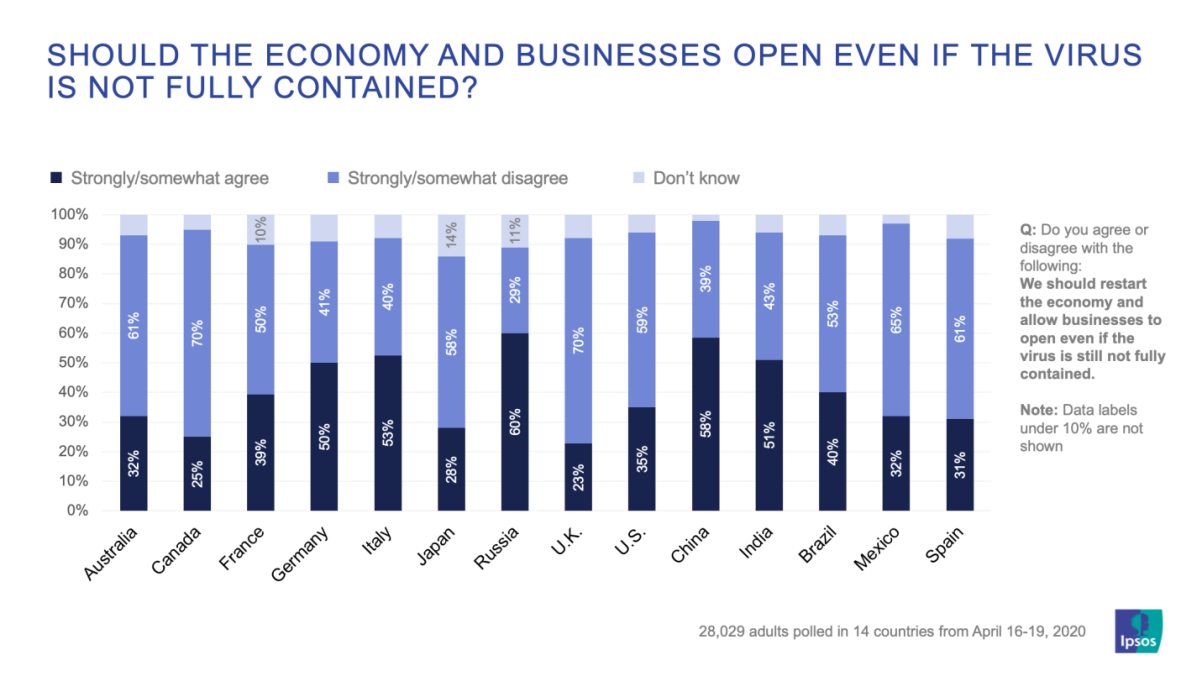

Most publics put the emphasis on public health over economic renewal. As Figure 1 shows, an April 19 Ipsos poll across 14 major countries finds an average 53-40% level of disagreement with the proposition that “we should restart the economy and allow businesses to open even if the virus is still not fully contained” (the average is not population-weighted across countries).

Nine of the 14 countries have a majority that disagrees with economic re-opening given the health risks, while five agree with the idea. Russia and China have the lowest levels of disagreement with this statement, 29% and 39%, respectively; while the UK and Canada have the strongest disagreement, both at 70%. The US is closer to these latter countries with a 59% majority disagreeing with the idea of economic re-opening before the virus is fully contained.

Figure 1: Support for prioritizing public health over economic re-opening (Ipsos)

There is a modest inverse correlation (-0.68) across these 14 countries between their annual “freedom scores,” published by Freedom House, and the share in each country who agree with economic opening despite the health risks; that is, the more free/democratic each country is, the less it tends to agree with re-opening the economy despite the health risks. There is also a modest but weaker inverse correlation (-0.41) between per capita GDP and the share who agree with prioritizing economic opening; that is, wealthier countries are somewhat less likely to support re-opening before the virus is contained.

An April 13 Kantar poll across the G-7 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, US) also finds a preference for prioritizing public health over economic re-opening. While 40% in these seven countries believe their government is striking the balance about right, 27% believe their government is putting too much emphasis on economic concerns, at the expense of public health; while only 20% believe their government is putting too much emphasis on public health, at the expense of the economy (figures are not population weighted). In five of the countries, there is a clear sense (at least a 3-point margin) that the government should put more emphasis on public health rather than the economy; in Germany opinion is roughly tied between the two options; in Italy, a 31-18% margin believes the government has not done enough to protect the economy, with 41% saying “they have got the balance about right.”[2]

Ukraine, like China, Russia, Germany, and perhaps Italy, is notable for appearing to prioritize economic recovery over protection of health. A KIIS March 30 poll there finds 43% saying “I am more afraid of the economic consequences of introducing quarantine restrictions,” compared to 34% who say “I am more afraid of the coronavirus epidemic in Ukraine.” Tracking data for this question from April 11 shows an even greater share (54%) concerned about economic consequences.

It is also notable that the public in Sweden, which has adopted policies that favor maintaining economic openness, rather than imposing stringent health restrictions, appear satisfied with the balance. Although polling in Sweden has not asked specific questions about the economic-health tradeoff, a study by scholars at the Uppsala University and other institutions finds that a 51% majority of Swedes feel their country’s response has been sufficient, compared to only 31% saying it has not been “forceful enough.”

The dominant global response, however, leans in favor of health; and this general global wariness about easing health protections may apply as well to other aspects of society beyond commerce. For example, an April 22 RTL INFO survey finds that a 64-21% majority of Belgians opposes re-opening schools in early May. In the US, an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll finds that fully 85% of Americans think it is a bad idea to reopen schools without first conducting further testing for coronavirus. In Spain, a 40dB poll finds that 71% of people agree with the government’s strict confinement rules for children.

There is mixed evidence on whether this dominant global focus on public health is receding. It could be that the preference for economic re-opening will grow as publics endure more months of economic distress. But at this point there is limited global time-series data on this question, and the data paints a mixed picture.

The April Kantar poll of the G-7 countries shows a very slight decline from their March poll in the average preference for public health across the seven countries. Across all the G-7 countries, the average 7-point margin in favor of public health (27-20%, as noted above) is down slightly from a 13-point margin in Kantar’s March survey (31-18%).[3]

Similarly, a GQR survey of the US public, conducted in two waves during April, shows a slight drop from the week of April 12 to the week of April 19 in the share who say they are “more worried about the spread of the illness in the US as a result of the pandemic,” rather than “more worried about the impact of the coronavirus on the US economy.” The 64-36% majority in the April 12 wave of the poll declines to a 57-43% margin in by April 19.

Tracking polls in the US by Navigator, however, show a late March jump in the preference for prioritizing health, and then a relatively steady preference after that. Navigator’s polling shows an initial split on March 23 between those who say they are “more worried about the impact of coronavirus on people’s health” (49%) and “the impact of coronavirus on the economy as a whole” (51%). By March 31, a 59-41% preference opens up on the side of people worrying about the impact on health; and that margin in Navigator’s polling has remained virtually unchanged as of their April 29 poll (59-41%).

Future movement on this question will likely depend not only on the level of economic distress publics are experiencing in each country, but also on the health consequences that may appear in the many places worldwide that are starting to re-open their economies.

Women may place a stronger emphasis on health than the economy, relative to men. Although gender breakdowns are not publicly available for many polls, in both the US and UK, there is a gender gap on the tradeoff between health protection and economic re-opening. An April 12 Pew poll in the US finds women are 8 points more likely to say they are concerned COVID-19 restrictions “will be lifted too quickly,” with 70% of women saying this, compared to 62% of men. One might dismiss this gap as simply reflecting partisan preferences, but the gap is almost entirely between Republican men and women, with 58% of Republican women worried about lifting health restrictions too quickly, compared to just 45% of Republican men (among Democrats, 80% of men and 81% of women feel this way).

In the UK as well, women are somewhat more likely to prioritize health protections. An April 24 Deltapoll finds that 66% of women are more worried about “Britain moving too quickly to lift restrictions,” compared to 59% of men. The Deltapoll finds a stronger emphasis on health protections among older respondents, compared to younger generations – a pattern that is not as pronounced in the US data.

Wording matters. As in all polling, the wording on this tradeoff has a big impact on the data.

Polls that offer a third option (e.g., that the government has the balance about right, as in the Kantar G-7 poll noted above) tend to draw a large share of responses to that choice – about 40% in the Kantar poll, and 39% in an April 17 Angus Reid poll in Canada. Nearly half of Americans (49%) in an April 9 CBS poll say they are thinking about both health and economic effects of the coronavirus equally. But in the Kantar polls and others that feature this kind of third choice, there is generally still a preference for prioritizing health protections.

Polls on this tension also differ on whether they ask about the respondent’s own tradeoffs on health and economic well-being, or whether they ask about what the priority should be for society as a whole. In the April 19 GQR poll in the US, a 57-42% majority was more personally worried about getting sick from the virus than about the impact on their personal financial well-being; but the margin was higher, 62-38% regarding the “spread of the illness in the US,” relative to “the impact of the coronavirus on the US economy.” In general, global polls suggest that higher shares of people are personally worried about financial harm resulting from the pandemic than about themselves or loved ones catching COVID-19, and that levels of concern about people’s personal financial situations are rising in many countries.

Polls differ, as well, on whether they are asking about current restrictions, or changes in restrictions. There appears to be a general tilt toward acceptance of existing restrictions and more resistance to changes in restrictions. For example, a March 29 Dart poll (full wording at the link) in Canada finds a 90-10% preference for health precautions over economic opening – higher than most other Canadian polls. But the wording for the first option begins, “we should stay the course, and…” The majority support for relatively relaxed health protections in Sweden, noted above, may reflect the fact that those policies are already in place.

Global concern about contracting the virus continues to be mostly stable, but with a slight increase

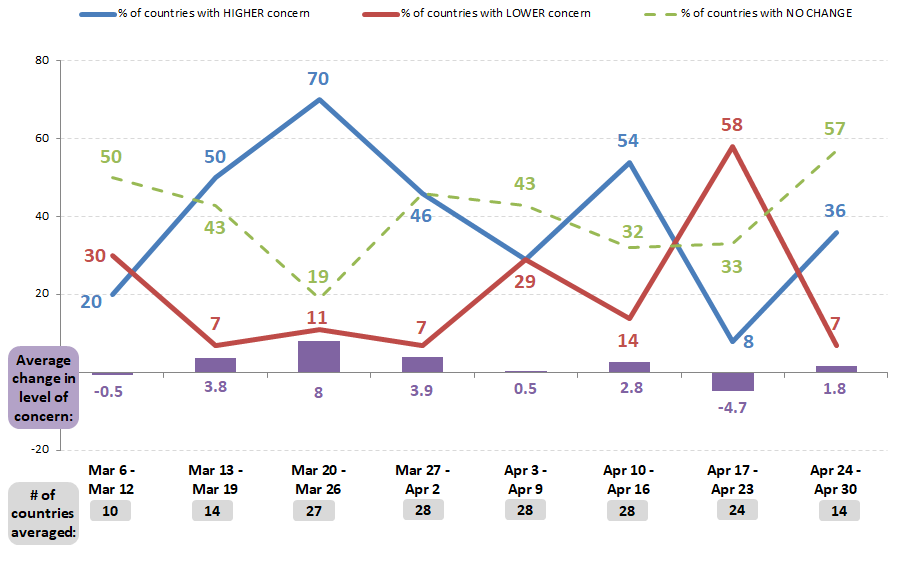

Global polling data this week shows that already-high worldwide levels of concern about contracting the coronavirus have mostly stabilized. As Figure 2 shows, a 57% majority of countries with relevant data show no major change (i.e., less than 3 points) in the share concerned about contracting COVID-19. [4] This is the highest level of countries with no major change in weekly levels of concern since we began tracking the data in early March.

Figure 2: % of countries with higher or lower levels of concern about contracting COVID-19

Overall, the average rise in level of concern about contracting COVID-19 is 1.8 points. This is a reversal from the previous week, but it is a far lower rate of increase than during mid-March, when average concern jumped a full 8 points in a single week.

Government job approval ratings on handling COVID-19 also remain relatively stable

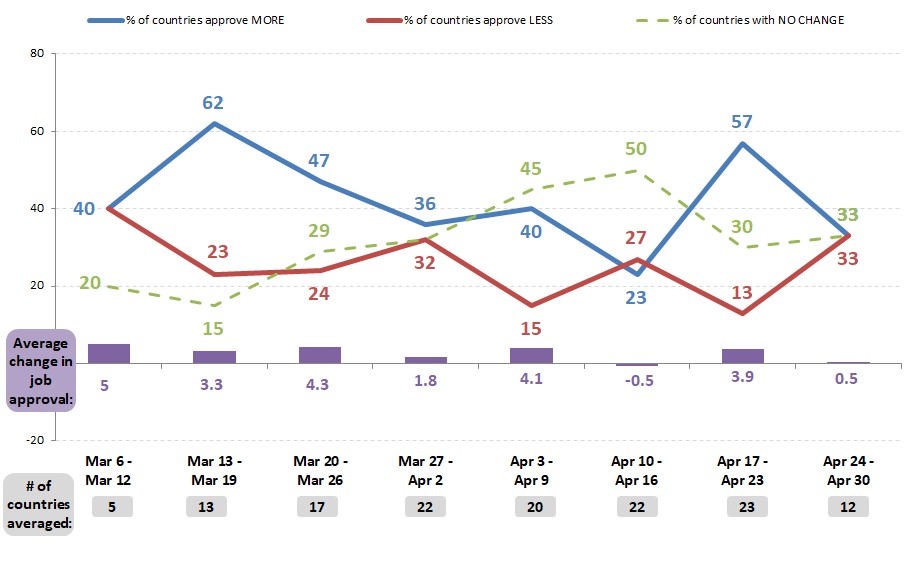

With concern about contracting coronavirus starting to stabilize, there is also some stabilization in approval for the job national governments are doing on handling the pandemic. As Figure 3 shows, one third of all countries with such data show no major change in government approval on handling COVID-19; one third show a rise in approval, and one third show a decline. Overall the average change in approval is up a half point.

Figure 3: % of countries with higher or lower levels of government job approval on handling COVID-19

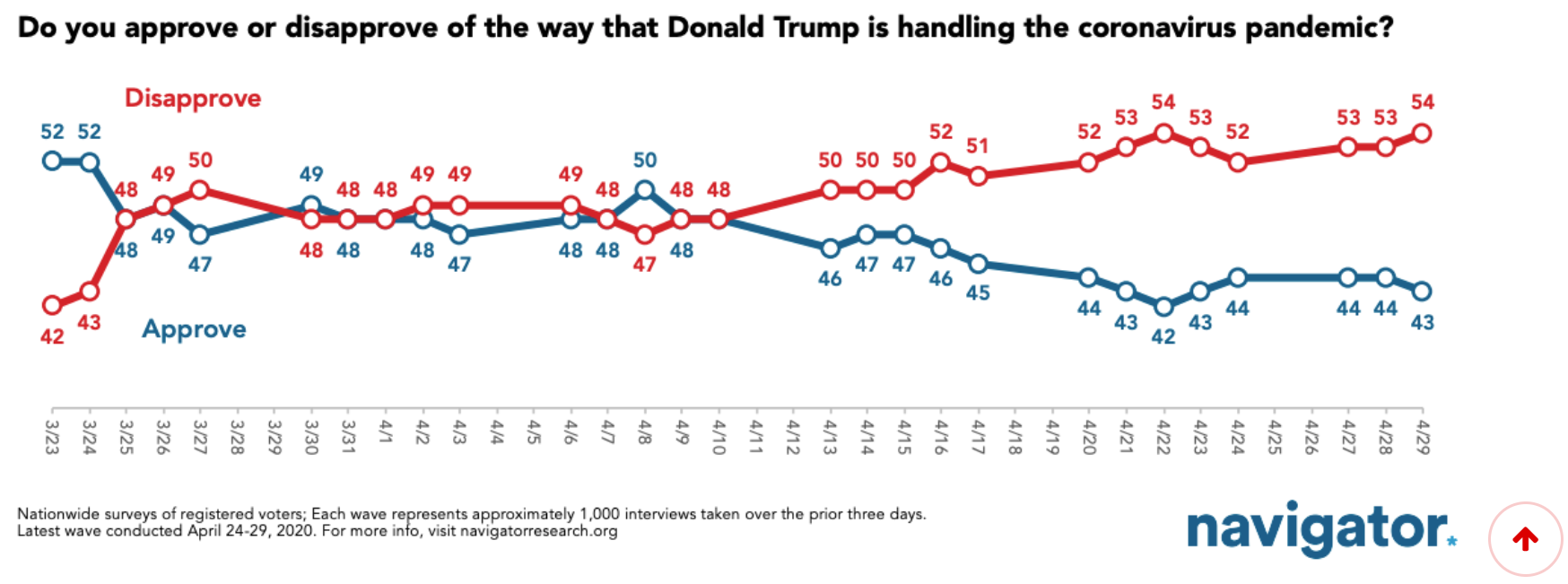

In contrast to the relatively stable picture globally, in the US, according to tracking polls from Navigator, public approval of Donald Trump’s handling of the coronavirus continues to erode gradually. As Figure 4 shows, on April 8, Trump enjoyed a slim 50-48% net approval rating on his handling of the pandemic; that is now down to a 43-54% net disapproval tying his highest disapproval rating to date.

In contrast to the relatively stable picture globally, in the US, according to tracking polls from Navigator, public approval of Donald Trump’s handling of the coronavirus continues to erode gradually. As Figure 4 shows, on April 8, Trump enjoyed a slim 50-48% net approval rating on his handling of the pandemic; that is now down to a 43-54% net disapproval tying his highest disapproval rating to date.

Figure 4: job approval of Trump’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic (Navigator)

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., the pandemic’s impact on mental health) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations.

Our first six installments of Pandemic PollWatch, on March 20 and 27, and April 2, 9, 16, and 23 reviewed a total of 519 polls from 96 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 106 polls, covering 50 countries, increasing the total number of geographies with reviewed public opinion data up to 97. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, polls reviewed here vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] The wording in the Kantar poll is: “Which of these comes closest to your view on how the [COUNTRY]

government is responding to the Coronavirus outbreak? Too much emphasis on protecting people’s health, and not enough on protecting the country’s economy; Too much emphasis on protecting the country’s economy, and not enough on protecting people’s health; They have the balance about right.”

[3] It is important to note that on a population-weighted basis there is no reduction in the margin who prefer a priority on health; indeed, on that basis, the margin focused on health actually increases, from a net 10 point margin, to a net 17 point margin.

[4] For both Figures 2 and 3, data compiled by GQR; data only compiled for countries having week-on-week public polling on the question shown. Countries only counted as showing an “increase/decrease” if the week’s change is at least 3 percentage points. Average for change in level of concern is not population-weighted across countries. Question wordings may differ somewhat across countries and weeks. In both Figures 2 and 3, the data from previous weeks has been revised slightly from last week’s edition of PollWatch to reflect late-arriving data.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- North Macedonia

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The polls reviewed for this edition of Pandemic PollWatch (with links in all possible cases) are listed below. The four earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.