an analysis of global public opinion on covid-19

What will the post-coronavirus world be like? We do not yet know precisely when or how the world will move past this pandemic; but as many countries begin the process of re-opening, global public opinion already provides insights on people’s expectations regarding life after COVID-19. This week’s edition of Pandemic PollWatch looks at how people around the world expect life will be like once the coronavirus threat has subsided, and how soon they expect that to occur.

This is the tenth in a series of weekly papers from GQR summarizing and analyzing all available data on global opinion on COVID-19, with a particular focus on the political implications of global opinion linked to the pandemic.[1] Earlier editions are here.

Major insights in this edition include:

- Global publics view the post-coronavirus period as a time when they will be on edge – about the economy, about traveling or socializing, and about how long “recovery” will take. Many expect to significantly curtail their economic and social activities – whether a vaccine exists or not. At the same time, large shares in many countries hope their national economies will not simply “return to normal,” but rather will seize this moment as an opportunity for major economic changes.

- More than 10 weeks into the pandemic, worldwide fears of contracting COVID-19 have largely stabilized, although at very high levels; 65% globally, on average, worry about getting the disease.

- Approval ratings for governments’ handling of the pandemic have also largely stabilized, although ratings in the US continue to drop.

Major Insights

Global publics view the post-coronavirus period as a time when they will be on edge – about the economy, about traveling or socializing, and about how long “recovery” will take. Many expect to significantly curtail their economic and social activities – whether a vaccine exists or not. At the same time, large shares in many countries hope their national economies will not simply “return to normal,” but rather will seize this moment as an opportunity for major economic changes.

As many countries and localities begin the process of re-opening, global surveys suggest the coronavirus is leaving major parts of the world on edge – pessimistic, cautious, nervous. Although many want the pandemic experience to open the door to big, positive changes in their countries’ economies, most expect a near-term future of tight finances, constrained social interaction, and a slow return to “normal.”

Expectations for long processes of national recovery. Surveys suggest that most publics expect it will require years, rather than months, to overcome the trauma of the pandemic. A Kekst CNC survey of five major countries (Germany, Japan, Sweden, UK, US) finds majority agreement that national impacts will be long-lasting. On average across the five countries (not weighted for population), 56% say generally that the impact on “their country” will last at least one year past 2020, rather than playing out by the end of this year. An even higher share, 68%, say the impact on their country’s “economy” will last for a year or longer past 2020.

Among these five countries, the British have the highest share expecting a long economic recovery, 87%; but even in the US, the most optimistic of the five countries, a 50% majority expect the economic recovery will continue long past 2020, despite their president’s assurance of an “incredibly strong” fourth quarter of 2020. In all these countries, expectations for a long recovery process are stronger among women, and most countries show longer expectations among older respondents. In the US, Democrats and Independents are also more likely to expect a longer process of recovery.

Most countries with survey data on this question show similar expectations for slow recovery:

- Greece. A May 5 survey in Greece conducted by About People finds a 61% majority expect the pandemic-caused economic crisis will last “about two years” or longer.

- Italy. A May 9 SWG survey in Italy finds 58% believe “the economy will not recover for a long time,” although that is down from 64% on April 26.

- South Africa. An April 24 McKinsey & Company survey in South Africa finds 29% expect the pandemic to produce a “lengthy recession,” with another 52% believing “the economy will be impacted for 6-12 months or longer and will stagnate or show slow growth thereafter”; only 19% expect the economy to rebound within three months.

- UAE and Saudi Arabia. YouGov’s April 15 surveys in these two countries find high and rising shares that expect the pandemic will have an impact on national economies in the United Arab Emirates (59%, up from 56% a week earlier) and Saudi Arabia (49%, up from 44% the previous week).

Norway is an exception to the pessimistic outlook, with 73% in a May 5 Kantar survey saying things look bright or very bright in the future as the country succeeds in dealing with coronavirus outbreak. In contrast to the dominant pattern in the five-country Kekst study, optimism in Norway increases with age.

Although many publics believe the national and economic damage from the coronavirus pandemic will be long-lasting, there are indications they may be more optimistic about their own lives returning to normal. In the Kekst study of Germany, Japan, Sweden, the UK and the US, respondents were on average (not weighted for country population) 17 points less likely to say that the impact on their “own life” would extend at least a year past 2020, relative to the shares who said the impact on their “country” would take that long.

It is possible that these gloomy economic expectations could tend to benefit incumbent governments, whose publics may now be braced for prolonged hard economic times, and will reward even minor signs of improvement. But if public expectations for long-term damage prove accurate, it could alternatively be the case that hard conditions erode political support for those in power.

Expectations for big drops in post-pandemic social and consumer activities. Global opinion research suggests publics worldwide expect major pull-backs in their post-pandemic social and economic activity. Of course, polls are more useful at revealing how people feel now – and much less useful at gauging how they will feel at some point in the distant future. But it is still notable that people across many countries expect big reductions in so many of their daily activities, even once the pandemic has ended.

The Kekst study of Germany, Japan, Sweden, the UK, and the US provides dramatic evidence on this point. Across seven major kinds of activities – traveling by plane, eating at restaurants, shopping at supermarkets, going out to movies, attending concerts or exhibitions, going to sports events, or using public transport – publics in these five countries expect to be doing less of each of these activities after the crisis is over than they did before, with an average net drop of 22% (3% say they will do more of these things, 25% less; each activity was tested separately; the averages here are not weighted by country population). Among these activities, only shopping at a supermarket had an average net drop in expected frequency that was not in double digits (across all five countries there was a net 9% who said they expected to shop less rather than more).

Polls from other countries bolster the impression that publics expect to pare back many of their social and economic activities, even once the pandemic has lifted. For example, a May 12 survey by Israel’s National Emergency Knowledge Research Center and the Ministry of Science and Technology finds that 53% of Israelis say they will not return to shopping malls as much as in the past, compared to just 17% who say they will. The survey finds 42% say they will reduce use of public transport, while 49% say they will resume their prior use of public transport, and 9% expect to increase it.

Not all the expectations about future changes are negative. Many surveys show a hope or expectation of greater ability to work from home. In the Kekst survey, respondents across the five countries surveyed expect a net increase of 8% in the degree to which they work from home after the pandemic. They also expect an 11% net increase in their time spent outside.

But most of the expectations are more negative, and some of the expectation of long-term reductions in social and economic activities may stem from a fear that there will be repeated waves of COVID-19. An April 26 Morning Consult poll finds that 79% of Americans believe there will be another wave of the disease during the coming year. Similarly, a May 4 Ipsos survey finds that 85% of the French expect another wave of COVID-19 in the fall.

Even development of an effective vaccine might not fully offset these expected changes. A huge variable in the post-pandemic period will be whether and when the world develops an effective vaccine (or treatment) for COVID-19. Yet, at least at this point, publics in many countries expect that development of an effective vaccine would only partly offset their expected reduction in social and economic activities.

The Kekst survey explored this question through a randomized split sample experiment: on the various activities listed above, half the sample in each country was asked if they would increase or decrease the activity after hearing this prefatory phrase: “Assume that a vaccine against coronavirus is eventually developed and rolled out universally. After the coronavirus crisis is over, how do you expect…?” The other half sample were not told to assume the existence of a vaccine. As one would expect, the net reduction in each of the seven activities listed above was less among the half samples that were asked these questions in the context of a universal vaccine. But the assumption of a vaccine did not wipe out the inclination to pull back on these activities. Among those who were not told to assume a vaccine, there was a net 27% reduction in these seven activities, across all five countries; but among those told to assume a vaccine were to exist, the reduction was still large, a net 18% drop.

Again, it is possible that people may feel and act differently than they currently expect to once a vaccine is actually developed, tested, and widely administered. But it is notable that publics in these countries would still expect to reduce these central activities by nearly a fifth, even if a vaccine exists.

Part of the concern about fully resuming former routines after the development of a vaccine may be linked to doubts about whether everyone will actually get vaccinated. The US has a particularly strong and politically polarized stream of skepticism about vaccines; a May 18 Morning Consult poll finds 14% in the US say they would not get vaccinated even if America developed a vaccine; the rate is more than twice as high among Republicans (19%) than among Democrats (9%). In other countries, there are also segments who say they would not get vaccinated: 7% say this in a March 29 Roy Morgan poll in Australia.

Despite negative expectations, many voters hope for fundamental economic post-pandemic changes. While these results suggest publics worldwide are generally skeptical about their economic activities “returning to normal,” the global polling also suggests that large numbers do not simply want to return to normal; instead, they want leaders to create something better than the economic conditions that existed before.

In the Kekst survey of Germany, Japan, Sweden, the UK, and the US, a 51-32% majority across the five countries (not population-weighted) agree that “this is an opportunity to fundamentally change how the economy works,” rejecting the alternative statement that “we should get the economy back to how it was.” The desire for economic change in the post-coronavirus period tends to be stronger among people in the five countries who identify with parties on the left; in the US it is also stronger among the young.

The environment is one area in which governments could have public support for major changes. In an April 19 Ipsos survey,[2] majorities in each of the 14 countries surveyed agreed with the statement: “In the economic recovery after Covid-19, it’s important that government actions prioritize climate change.” Publics do not seem eager for their governments to shortchange the environment as they work to heal the pandemic’s economic damage; majorities or pluralities in 10 of the 14 countries Ipsos surveyed disagree with the idea that “Government should focus on helping the economy to recover first and foremost, even if that means taking some actions that are bad for the environment.”

More than 10 weeks into the pandemic, worldwide fears of contracting COVID-19 have largely stabilized, although at very high levels.

More than 10 weeks since the WHO declared the coronavirus outbreak a “pandemic,” global worries about contracting the virus remains high. Over the last two weeks, an average of 65% of respondents across 21 countries say they are concerned about contracting the disease (not population-weighted across countries; question wordings vary somewhat).

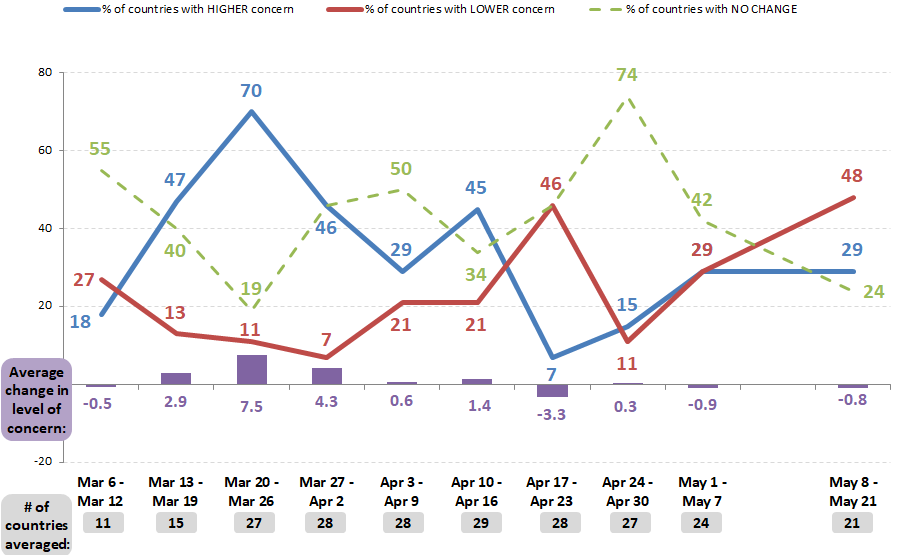

Yet, as Figure 1 shows, these concerns have largely stabilized and even started to abate slightly. In 72% of the countries reporting such data over the past two weeks, the share of people expressing this concern is either stable (no change of at least three percentage points in either direction), or has gone down. Concern has only increased in 29% of the countries. Across all these countries, the average level of concern drops by nearly 1 percentage point.

Figure 1: % of countries with increase, decrease in public’s concern about contracting COVID-19[3]

Approval ratings for governments’ handling of the pandemic have also largely stabilized, although ratings in the US continue to drop.

During the early weeks of the pandemic, there was a notable bump in approval ratings for governments’ handling of the pandemic. After more than two months of governments grappling with this crisis, those ratings have now largely stabilized.

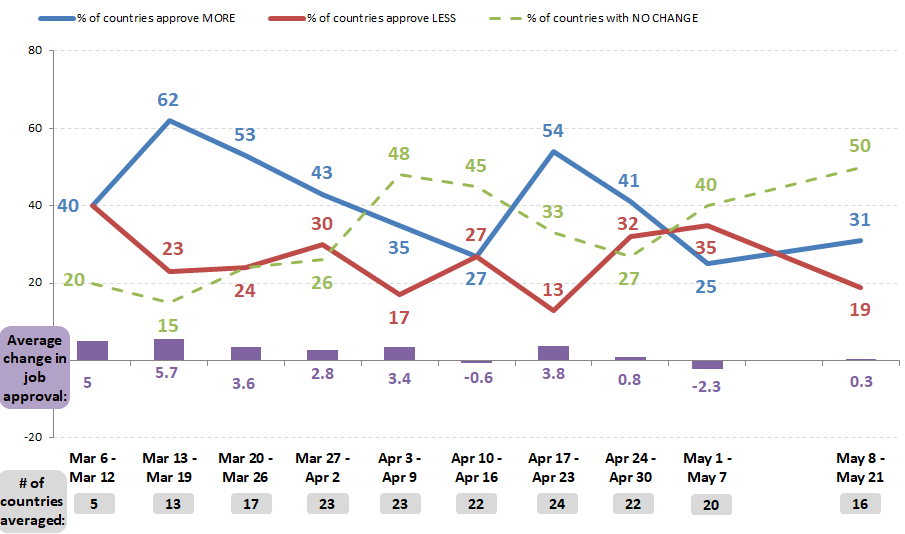

As Figure 2 shows, fully half of the countries reporting such data on a regular basis show no major change (less than three points change in either direction) in the coronavirus job approval ratings for their governments. Among the rest, more show higher approval ratings. On average, across the countries with such data, the job approval rating for handling the pandemic is up 0.3 percentage points – relatively unchanged.

Figure 2: % of countries with increase, decrease in government’s pandemic job approval rating

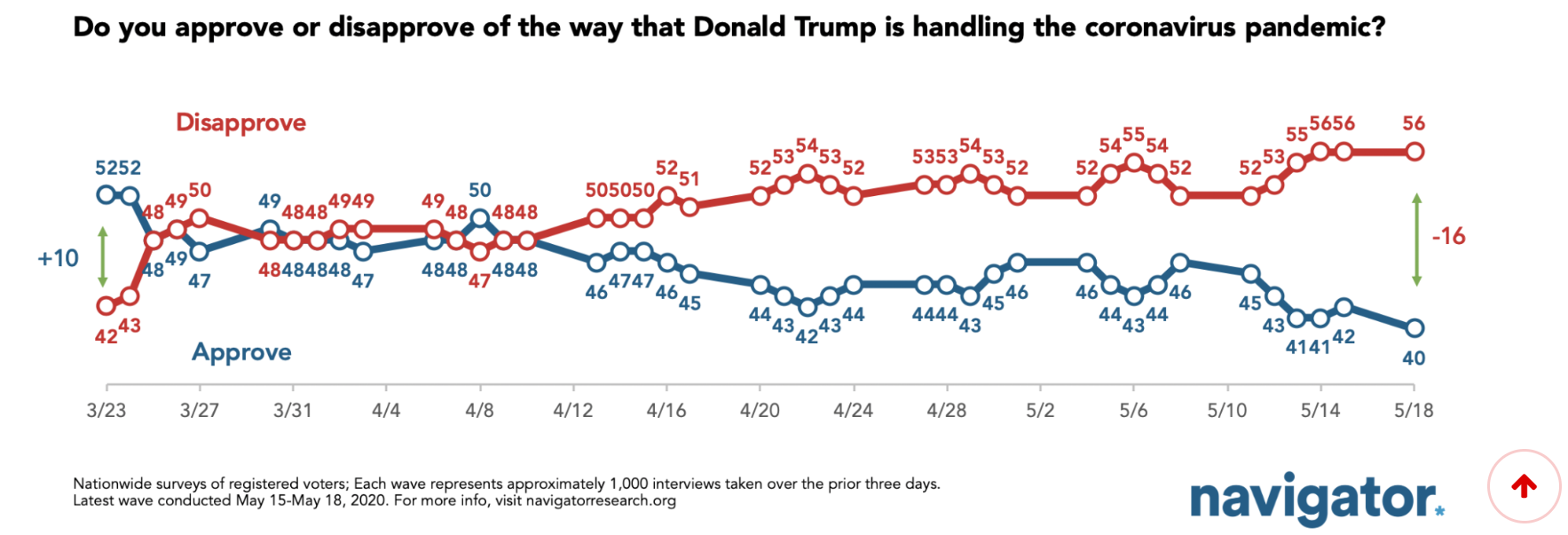

The US continues to be an outlier from this overall picture of stability. As Figure 3 shows, tracking polls by Navigator show approval ratings for President Donald Trump’s handling of the coronavirus continue to fall, and have now hit their lowest point yet, with a 40-56% net disapproval rating.

Figure 3: job approval rating for Donald Trump on handling the coronavirus pandemic (Navigator)

[1] These papers are not exhaustive in summarizing the global opinion research; there are many aspects (e.g., the pandemic’s impact on marriages) not discussed here. Instead, we are focusing on selected aspects of available global opinion research, with an emphasis on political implications, and providing links to all polls identified, so others have a resource for their own investigations.

Our first nine installments of Pandemic PollWatch, from March 20 through May 14, reviewed a total of 831 polls from 98 different geographies (generally countries, but also polling for Hong Kong). This week’s analysis reviews an additional 101 polls, covering 49 countries, increasing the total number of geographies with reviewed public opinion data up to 99. Links to all polls reviewed are listed here. As the Appendix notes, polls reviewed here vary significantly in methodology and reliability.

[2] The countries surveyed are: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Great Britain, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Spain, and the United States.

[3] In both Figures 1 and 2, data on the percentage of countries showing change are not population-weighted by country. The mix of countries reporting such data is not identical from period to period. The data for the current period combines all polls over the past two weeks, since there were very few polls available in time for last week’s edition.

Appendix

This analysis is based on available global public opinion research on the COVID-19 pandemic. We welcome input from others – including insights about opinion trends and dynamics, and about additional public opinion research that is not included here.

Countries and territories with published public opinion data on COVID-19 at this point include:

- Afghanistan

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Australia

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Belgium

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Brazil

- Bulgaria

- Canada

- Chile

- China

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cote d’Ivoire

- Croatia

- Cuba

- Cyprus

- Czechia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Denmark

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- Egypt

- El Salvador

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Georgia

- Germany

- Ghana

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Hong Kong

- Hungary

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya

- Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malaysia

- Malta

- Mexico

- Montenegro

- Morocco

- Mozambique

- The Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria

- North Macedonia

- Norway

- Pakistan

- Palestine

- Panama

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Philippines

- Poland

- Portugal

- Qatar

- Romania

- Russia

- Rwanda

- Saudi Arabia

- Serbia

- Singapore

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- Tanzania

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Ukraine

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

- Zambia

The reliability of the public opinion data from these geographies varies – and affects the analysis – for several reasons. First, some of these countries, such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, are “not free” (according to rankings by Freedom House) and respondents in these countries may not feel free to give their actual opinions in a survey.

Second, some of the polling organizations quoted in these reports may have stronger or weaker records regarding accuracy, methodological rigor, transparency, and other procedural factors that affect the reliability of their findings.

Third, the methodologies used in these surveys vary, and few are “gold standard” quality. The pandemic has driven researchers in most geographies to rely on online surveys, which generally do not have probability-based samples and can suffer from opt-in bias. Sample sizes and quality control procedures also vary across the available surveys.

The nine earlier editions of Pandemic PollWatch, available here, include links to all the previous COVID-19-related polls summarized in this series.

All polls reviewed so far, including in this edition, can be found in the full bibliography here.